Architecture of Mesopotamia

메소포타미아 건축은 티그리스-유프라테스 수계(水系)(일명 메소포타미아) 유역의 고대 건축으로, 여러 개별적인 문화를 포함하며 최초의 영구적인 구조물이 건설된 기원전 1만 년부터 기원전 6백 년까지의 기간에 걸쳐 있다. 메소포타미아인들의 건축적 업적 중에는 도시계획, 안뜰집, 지구라트의 개발이 있다. 메소포타미아에는 건축업이 존재하지 않았지만, 서기관이 정부, 귀족 또는 왕족을 위해 초안을 작성하고 건설을 관리했다.

The architecture of Mesopotamia is ancient architecture of the region of the Tigris–Euphrates river system (also known as Mesopotamia), encompassing several distinct cultures and spanning a period from the 10th millennium BC, when the first permanent structures were built in the 6th century BC. Among the Mesopotamian architectural accomplishments are the development of urban planning, the courtyard house, and ziggurats. No architectural profession existed in Mesopotamia; however, scribes drafted and managed construction for the government, nobility, or royalty.

고대 메소포타미아 건축에 대한 연구는 이용 가능한 고고학적 증거, 건물의 회화적 표현, 그리고 건축 관행에 관한 문헌에 기초하고 있다. 아키발트 세이스(1845~1933)에 따르면, 우르크 시대의 원시적인 상형문자는 다음 내용을 시사한다. “돌은 드물었지만, 이미 블록과 인장으로 잘려 있었다. 벽돌은 일반적인 건축 자재였으며, 벽돌로 도시, 요새, 사원, 주택이 건설되었다. 도시는 탑으로 이루어져 있었고 인공 플랫폼 위에 세워졌으며, 주택 또한 탑 같은 모습을 하고 있었다. 문은 경첩으로 달려 있어 열쇠 같은 것으로 열 수 있었고, 도시의 성 문은 더 큰 규모로 되어 있었으며 이중 구조였던 것으로 보인다. … 새처럼 날개가 있는 악마는 두려움의 대상이었으며, 집의 주춧돌 – 이라기보다는 벽돌 – 은 그 아래에 특정한 물건들을 넣어 봉헌되었다.”

The study of ancient Mesopotamian architecture is based on available archaeological evidence, pictorial representation of buildings, and texts on building practices. According to Archibald Sayce, the primitive pictographs of the Uruk period era suggest that “Stone was scarce, but was already cut into blocks and seals. Brick was the ordinary building material, and with it cities, forts, temples and houses were constructed. The city was provided with towers and stood on an artificial platform; the house also had a tower-like appearance. It was provided with a door which turned on a hinge, and could be opened with a sort of key; the city gate was on a larger scale, and seems to have been double. … Demons were feared who had wings like a bird, and the foundation stones – or rather bricks – of a house were consecrated by certain objects that were deposited under them.”

학술 문헌은 대개 사원, 궁전, 성벽과 성문 그리고 기타 기념비적인 건물들의 건축에 중점을 두지만, 간혹 주거용 건축 작업도 발견된다. 고고학적 지표조사를 통해 초기 메소포타미아 도시의 도시형태도 연구할 수 있었다.

Scholarly literature usually concentrates on the architecture of temples, palaces, city walls and gates, and other monumental buildings, but occasionally one finds works on residential architecture as well. Archaeological surface surveys also allowed for the study of urban form in early Mesopotamian cities.

건물 재료

Building Material

수메르 벽돌은 때때로 역청이 사용되기도 했지만 모르타르를 사용하지 않았다. 시간이 지남에 따라 크게 달라진 벽돌 스타일은 시대별로 분류된다.

Sumerian masonry was usually mortarless although bitumen was sometimes used. Brick styles, which varied greatly over time, are categorized by period.

- 팟슨(햇볕에 말린 원기둥 형태의 흙벽돌) 80 × 40 × 15 cm : 우루크 후기 (기원전 3600~3200년)

- 리므헨(일건연와, 햇볕에 말린 흙벽돌) 16 × 16 cm : 우루크 후기 (기원전 3600~3200년)

- 플라노-컨벡스(한쪽면이 반달형인 벽돌) 10x19x34 cm : 초기 왕조 시대 (기원전 3100~2300년)

- Patzen 80×40×15 cm: Late Uruk period (3600–3200 BC)

- Riemchen 16×16 cm: Late Uruk period (3600–3200 BC)

- Plano-convex 10x19x34 cm: Early Dynastic Period (3100–2300 BC)

메소포타미아 벽돌공들은 다소 불안정한 둥근 벽돌을 선호했기 때문에, 몇 줄 간격으로 벽돌을 수직으로 쌓아 올렸다. 플라노-컨벡스 벽돌의 장점은 제조 속도가 빠를 뿐만 아니라 표면이 불규칙하여 다른 벽돌 유형의 매끄러운 표면보다 마감 석고 코트가 더 잘 유지된다는 점이다.

The favoured design was rounded bricks, which are somewhat unstable, so Mesopotamian bricklayers would lay a row of bricks perpendicular to the rest every few rows. The advantages to plano-convex bricks were the speed of manufacture as well as the irregular surface which held the finishing plaster coat better than a smooth surface from other brick types.

벽돌은 햇볕에 단단하게 소성시켰다. 이런 종류의 벽돌은 오븐에서 구운 벽돌보다 내구성이 훨씬 떨어지기 때문에 결국 건물은 악화되었다. 건물들은 주기적으로 파괴되고, 평평해지고, 같은 자리에 재건되었다. 이 계획된 구조적 생애주기는 점차적으로 도시의 레벨을 높였고, 그래서 그들은 주변 평야보다 높은 곳에 위치하게 되었다. 그 결과로 만들어진 마운드는 텔(tell)로 알려져 있으며, 고대 근동 전역에서 발견된다. 관공서 건물들은 색을 입힌 돌의 원뿔, 테라코타 패널, 점토 못을 어도비 벽돌에 박아서 건물의 파사드를 장식하는 보호 덮개를 만들어 부패를 늦췄다. 특히 레바논에서 온 삼나무, 아라비아에서 온 섬록암, 인도에서 온 청금석 같은 수입 건축 자재를 귀하게 여겼다.

Bricks were sun baked to harden them. These types of bricks are much less durable than oven-baked ones so buildings eventually deteriorated. They were periodically destroyed, leveled, and rebuilt on the same spot. This planned structural life cycle gradually raised the level of cities, so that they came to be elevated above the surrounding plain. The resulting mounds are known as tells, and are found throughout the ancient Near East. Civic buildings slowed decay by using cones of coloured stone, terracotta panels, and clay nails driven into the adobe-brick to create a protective sheath that decorated the façade. Specially prized were imported building materials such as cedar from Lebanon, diorite from Arabia, and lapis lazuli from India.

바빌로니아 사원은 조악한 벽돌로 이루어진 거대한 구조물로, 부벽에 의해 지지되고, 빗물은 배수구로 흘러나간다. 우르에 있는 배수구 중 하나는 납으로 만들어졌다. 벽돌의 사용은 벽기둥(필라스터)과 기둥, 프레스코화와 에나멜 타일의 초기 개발로 이어졌다. 벽은 화려하게 채색되었고, 때로는 타일 뿐 아니라 아연이나 금으로 도금되었다. 횃불용으로, 칠한 테라코타 콘(원뿔)도 석고 안에 박혀 있었다. 바빌로니아 건축을 모방한 아시리아는 돌이 나라의 자연 건축자재였을 때에도 벽돌로 궁전과 사원을 지었는데 ㅡ 바빌로니아의 습한 토양에는 필요했지만 북쪽에서는 거의 필요하지 않은 벽돌 기단을 충실히 보존했다.

Babylonian temples are massive structures of crude brick, supported by buttresses, the rain being carried off by drains. One such drain at Ur was made of lead. The use of brick led to the early development of the pilaster and column, and of frescoes and enamelled tiles. The walls were brilliantly coloured, and sometimes plated with zinc or gold, as well as with tiles. Painted terracotta cones for torches were also embedded in the plaster. Assyria, imitating Babylonian architecture, also built its palaces and temples of brick, even when stone was the natural building material of the country – faithfully preserving the brick platform, necessary in the marshy soil of Babylonia, but little needed in the north.

장식

Decoration

그렇지만, 시간이 지남에 따라, 후기 아시리아 건축가들은 바빌로니아의 영향에서 벗어나 벽돌뿐만 아니라 돌을 사용하기 시작했다. 아시리아 궁전의 벽은 칼데아(바빌로니아 남부 지방의 고대 왕국)에서처럼 칠해지는 대신 조각과 채색된 석판이 늘어서 있었다. 이러한 부조(상)의 예술에서 활달하지만 단순한 아슈르나시르팔 2세 시대, 신중하면서 현실적인 사르곤 2세 시대, 세련되지만 대담함을 추구한 아슈르바니팔 시대의 세 단계를 추적할 수 있다.

As time went on, however, later Assyrian architects began to shake themselves free of Babylonian influence, and to use stone as well as brick. The walls of Assyrian palaces were lined with sculptured and coloured slabs of stone, instead of being painted as in Chaldea. Three stages may be traced in the art of these bas-reliefs: it is vigorous but simple under Ashurnasirpal II, careful and realistic under Sargon II, and refined but wanting in boldness under Ashurbanipal.

바빌로니아에서는 부조 대신에 둥근 입체 형상을 더 많이 사용했는데, 가장 초기의 사례로는 다소 서툴지만 현실적인 기르수(Girsu)의 조각상들이 있다. 돌이 부족한 바빌로니아는 조약돌 하나하나를 귀하게 다루었고, 높은 완성도의 보석 세공 기술을 이끌어냈다. 아카드의 사르곤 시대에 만들어진 두 개의 원통-인장이 그 종류 중 가장 훌륭한 사례다. 고고학자들이 발견한 초기 야금술의 첫 번째 주목할만한 표본 중 하나는 엔테메나의 은제 화병이다. 후기 시대에는 귀걸이와 금팔찌 같은 장신구 제조에서 탁월한 성과를 거두었다. 구리 역시 숙련된 솜씨로 가공되었으며, 실제로 바빌로니아는 구리 가공의 원조였을 가능성이 있다.

In Babylonia, in place of the bas relief, there is greater use of three-dimensional figures in the round – the earliest examples being the statues from Girsu, that are realistic if somewhat clumsy. The paucity of stone in Babylonia made every pebble precious, and led to a high perfection in the art of gem-cutting. Two seal-cylinders from the age of Sargon of Akkad are among the best examples of their kind. One of the first remarkable specimens of early metallurgy to be discovered by archaeologists is the silver vase of Entemena. At a later epoch, great excellence was attained in the manufacture of such jewellery as earrings and bracelets of gold. Copper, too, was worked with skill; indeed, it is possible that Babylonia was the original home of copper-working.

아시리아 사람들은 일찍부터 자수와 양탄자로 유명했다. 아시리아 도자기의 형태는 우아하며, 니네베 궁전에서 발견된 유리와 같은 (경질의) 도자기는 이집트 모델에서 파생된 것이다. 투명한 유리는 사르곤 통치 시기에 처음 도입된 것으로 보인다. 돌, 점토, 유리는 꽃병을 만드는데 사용되었으며, 이집트 초기 왕조 시대와 비슷한 단단한 돌 화병이 기르수에서 출토되었다.

The people were famous at an early date for their embroideries and rugs. The forms of Assyrian pottery are graceful; the porcelain, like the glass discovered in the palaces of Nineveh, was derived from Egyptian models. Transparent glass seems to have been first introduced in the reign of Sargon. Stone, clay and glass were used to make vases, and vases of hard stone have been dug up at Girsu similar to those of the early dynastic period of Egypt.

도시계획

Urban planning

수메르는 도시 자체를 건설하고 진보된 형태로 건설한 최초의 사회였다. 우르크(이라크 남부 유프라테스 강 부근에 있었던 고대 수메르의 도시)의 성벽, 거리, 시장, 사원, 정원에 대한 설명으로 시작되는 길가메쉬 서사시에서 알 수 있듯이 그들은 이 업적을 자랑스럽게 생각했다. 우르크는 식민지 개척과 정복을 통해 서아시아 전역으로 퍼져나간 도시 문화의 표본이 되었으며, 사회가 더 크고 더 정교해짐에 따라 더욱 확산되었다.

The Sumerians were the first society to construct the city itself as a built and advanced form. They were proud of this achievement as attested in the Epic of Gilgamesh, which opens with a description of Uruk—its walls, streets, markets, temples, and gardens. Uruk became the template of an urban culture which spread throughout Western Asia via colonization and conquest, and more generally as societies became larger and more sophisticated.

도시 건설은 신석기 혁명에서 시작된 유행의 최종 산물이었다. 도시의 성장은 부분적으로는 계획되었고 부분적으로는 유기적으로 이루어졌다. 계획은 성벽, 높은 사원 지구, 항구의 주요 운하, 중심가 등에서 명백하게 드러난다. 주거 및 상업 공간의 보다 세밀한 구조는 계획된 지역에 의해 부과된 공간적 한계에 대한 경제적 힘의 반작용으로 규칙적인 특징을 가진 불규칙한 디자인을 초래한다. 수메르인들은 부동산 거래를 기록했기 때문에, 도시성장패턴, 밀도, 자산가치 및 기타 지표의 많은 부분을 설형문자 텍스트 소스에서 재구성할 수 있다. 전형적인 도시는 공간을 주거공간, 복합용도공간, 상업공간, 시민 공간으로 구분했다. 주거 지역은 직업별로 그룹화되었다. 도시의 중심에는 항상 지리적 중심에서 약간 떨어진 곳에 위치한 높은 사원 단지가 있었다. 이 높은 사원은 일반적으로 도시의 설립 이전부터 존재했으며 도시 형태가 성장하는 핵(중심지)이었다. 성문에 인접한 지역은 특별한 종교적, 경제적 기능을 담당했다.

The construction of cities was the end product of trends which began in the Neolithic Revolution. The growth of the city was partly planned and partly organic. Planning is evident in the walls, high temple district, main canal with harbor, and main street. The finer structure of residential and commercial spaces is the reaction of economic forces to the spatial limits imposed by the planned areas resulting in an irregular design with regular features. Because the Sumerians recorded real estate transactions it is possible to reconstruct much of the urban growth pattern, density, property value, and other metrics from cuneiform text sources. The typical city divided space into residential, mixed use, commercial, and civic spaces. The residential areas were grouped by profession. At the core of the city was a high temple complex always sited slightly off of the geographical centre. This high temple usually predated the founding of the city and was the nucleus around which the urban form grew. The districts adjacent to gates had a special religious and economic function.

이 도시는 항상 작은 촌락을 포함한 관개 농경지 벨트가 포함되어 있었다. 도로와 운하의 네트워크가 도시와 이 땅을 연결시켰다. 교통망은 넓은 행렬 도로(아카드어: sūqu ilāni u šarri), 공공 통과 도로(아카드어: sūqu nišī), 개인 소유 막다른 골목(Akkadian:mūṣû)의 3단으로 조직되었다. 블록을 규정하는 공공 도로는 시간이 지남에 따라 거의 변하지 않는 반면, 막다른 골목은 훨씬 더 유동적이었다. 현재의 추정치에 따르면 도시 면적의 10%가 도로, 90%가 건물이었다. 그렇지만, 운하가 도로보다 더 중요한 교통 수단이었다.

The city always included a belt of irrigated agricultural land including small hamlets. A network of roads and canals connected the city to this land. The transportation network was organized in three tiers: wide processional streets (Akkadian:sūqu ilāni u šarri), public through streets (Akkadian:sūqu nišī), and private blind alleys (Akkadian:mūṣû). The public streets that defined a block varied little over time while the blind-alleys were much more fluid. The current estimate is 10% of the city area was streets and 90% buildings. The canals; however, were more important than roads for good transportation.

주택

Houses

메소포타미아인들의 집을 짓는데 사용된 재료는 오늘날과 비슷하지만 정확하지는 않다: 진흙 벽돌, 진흙 회반죽, 나무 문들은 (비록 수메르 일부 도시에서는 나무가 흔하지 않았지만) 모두 도시 주변에서 자연적으로 구할 수 있었다. 대부분의 집은 정사각형의 중앙 실에 다른 방들이 붙어 있었지만, 집의 크기와 재료가 매우 다양한 것으로 보아 주민들이 직접 지은 것으로 추정된다. 가장 작은 방이 가장 가난한 사람들의 거처가 아닐 수 있다; 실제로, 가장 가난한 사람들은 도시 외곽에서 갈대 같은 부패하기 쉬운 재료로 집을 지었을 가능성이 있지만, 이에 대한 직접적인 증거는 거의 없다. 집에는 상점, 작업장, 창고, 가축이 있을 수 있다.

The materials used to build a Mesopotamian house were similar but not exact as those used today: mud brick, mud plaster and wooden doors, which were all naturally available around the city, although wood was not common in some cities of Sumer. Most houses had a square centre room with other rooms attached to it, but a great variation in the size and materials used to build the houses suggest they were built by the inhabitants themselves. The smallest rooms may not have coincided with the poorest people; in fact, it could be that the poorest people built houses out of perishable materials such as reeds on the outside of the city, but there is very little direct evidence for this. Houses could have shops, workshops, storage rooms, and livestock in them.

주거 디자인은 우바이드 주택에서 직접적으로 발전했다. 비록 수메르의 원통 인장은 갈대-집(reed house)을 묘사하고 있지만, 안뜰-집(courtyard house)이 지배적인 유형이었으며 메소포타미아에서 오늘날까지 사용되고 있다. é(설형문자:𒂍, E2; 수메르어:e2; 아카드어:bītu)라고 불리는이 집은 대류를 생성하여 냉각 효과를 제공하는 개방된 안뜰(안마당)을 향해 열려 있었다. tarbaṣu(아카드어)라고 불리는 이 안뜰은 집의 주요 구성 요소였으며, 모든 방이 그 안으로 열려 있었다. 외벽은 별다른 특징이 없었고 집과 거리를 연결하는 단 하나의 개구부만 있었다. 집과 거리 사이를 이동하려면 작은 대기실을 통해 90° 회전해야 했다. 거리에서는 열린 문을 통해 대기실의 뒷벽만 볼 수 있었으며, 마찬가지로 안뜰에서는 거리가 보이지 않았다. 수메르인들은 공적 공간과 사적 공간을 엄격하게 구분했다. 수메르 주택의 전형적인 크기는 90㎡였다.

Residential design was a direct development from Ubaid houses. Although Sumerian cylinder seals depict reed houses, the courtyard house was the predominant typology, which has been used in Mesopotamia to the present day. This house called é (Cuneiform: 𒂍, E2; Sumerian: e2; Akkadian: bītu) faced inward toward an open courtyard which provided a cooling effect by creating convection currents. This courtyard called tarbaṣu (Akkadian) was the primary organizing feature of the house, all the rooms opened into it. The external walls were featureless with only a single opening connecting the house to the street. Movement between the house and street required a 90° turn through a small antechamber. From the street only the rear wall of the antechamber would be visible through an open door, likewise there was no view of the street from the courtyard. The Sumerians had a strict division of public and private spaces. The typical size for a Sumerian house was 90 ㎡.

시공

Construction

간단한 집은 갈대 다발을 묶어서 땅에 박아 넣는 방식으로 지을 수 있었다. 좀 더 복잡한 집은 돌 기초 위에 지어졌으며, 진흙벽돌로 집을 만들었다. 나무, 마름돌 블록, 잔해 역시 집을 짓는 데 널리 사용된 재료였다. 진흙벽돌은 진흙과 잘게 썬 짚으로 만들었다. 이 혼합물을 틀에 넣은 다음 햇볕에 말려 건조시켰다. 벽에는 진흙 반죽, 그리고 지붕에는 진흙과 포플러 목재를 사용했다. 우바이드 시대의 집은 벽에 내화 점토를 눌러 붙였다. 벽에는 예술 작품이 그려지기도 했다. 지붕은 갈대로 덮인 야자나무 판자로 만들 수도 있었다. 지붕 위는 벽돌이나 나무 계단을 통해 집과 연결되었다. 구운 벽돌은 매우 비싸서, 고급스러운 건물을 만드는 데만 사용되었다. 문과 문틀은 나무로 만들었다. 때로는 소가죽으로 문을 만들기도 했다. 집과 집 사이의 문은 종종 너무 낮아서 사람들이 몸을 웅크리고 걸어서 통과해야 했다. 집에는 보통 창문이 없었으며, 창문이 있다면 진흙이나 나무 창살로 만들었다. 바닥은 보통 흙으로 만들어졌다. 메소포타미아의 집은 종종 허물어졌다. 집은 자주 수리해야 했다.

Simple houses could be constructed out of bundles of reeds which would be tied together, and then inserted into the ground. More complex houses were constructed on stone foundations, with the house being made out of mudbrick. Wood, ashlar blocks, and rubble were also popular materials used to make houses. The mudbrick was made from clay and chopped straw. This mixture was packed into molds and then left in the sun to dry. They used mud plaster for the walls, and mud and poplar for the roof. In the Ubaid period houses would be fire clay pressed into the walls. Walls would also have artwork painted on them. Roofs could also be made planks of palm tree wood which would be covered in reeds. The top of the roof would be connected to the house through brick or wood stairs. Baked bricks were very expensive, and thus they were only used to make luxurious buildings. Doors and door frames were made from wood. Sometimes Doors were made from ox-hide. Doors between houses were often so low, that people needed to crouch to walk though them. Houses would usually have no windows, if they did it would be made of clay or wooden grilles. Floors would usually be made of dirt. Mesopotamian houses would often crumble. Houses needed to be repaired often.

디자인

Design

우바이드 시대의 집은 세 부분으로 나뉜 구조일 것이다. 지붕이 있는 긴 중앙 복도와 그 양쪽에 연결된 작은 복도가 있었다. 중앙 복도는 식사 및 공동 활동을 위해 사용되었을 가능성이 있다. 우바이드 주택에는 다양성이 있었다. 어떤 집들은 다른 집들보다 더 풍부한 인공물 유물군들을 포함하고 있었다. 우바이드 집들은 다른 집들과 서로 연결될 수도 있었다. 우바이드 주택의 건축 양식은 우바이드 사원과 구분이 안 된다. 우르크 시대에는 집의 형태가 다양했다. 어떤 집은 직사각형이었고 다른 집은 원형이었다. 메소포타미아의 일부 집들에는 방이 하나 뿐인 반면, 다른 집들은 방이 많았다. 가끔 이 방들 중 일부는 지하실로 사용되기도 했다. 기원전 3000년대, 메소포타미아에 안뜰이 도입되었다. 안뜰은 메소포타미아 건축 양식의 기초가 되었다. 이 안뜰은 두꺼운 벽으로 된 홀에 둘러싸여 있었다. 이 홀은 아마도 손님들을 위한 응접실이었을 것이다. 대부분의 주택에는 2층이 있었을 가능성이 높다. 위층은 식사, 수면, 접대를 위해 사용되었을 수 있으며, 침실도 있었을 수 있다. 사람들은 지붕 위에 채소를 심거나 종교 의식을 거행했을 것이다. 1층은 상점, 작업장, 창고, 가축을 기르는 공간으로 사용되었을 것이다. 방 하나는 보통 성소로 사용되었다.

In the Ubaid period houses would be tripartite homes. They had a long roofed central hallway that smaller connected to on either of its sides. It is possible that the central hallway was used for dining and communal activities. There was variety in Ubaid houses. Some houses contained richer artifact assemblage than other houses. Ubaid houses could also be interconnect with other houses. The architecture of Ubaid houses is indistinguishable from Ubaid Temples. During the Uruk period houses had various shapes. Some houses were rectangular, others were round. Some houses in Mesopotamia had only one room, while others had many rooms. Occasionally some of these rooms would serve as basements. In the 3000’s BCE, courtyards were introduced to Mesopotamia. Courtyards would become the basis for Mesopotamian architecture. These courtyards would be surrounded by thick walled halls. These halls were probably reception rooms for guests. It is likely that most houses had an upper storey. The upper storey might have been used dining, sleeping, and entertaining, and might have also housed the bedrooms. People would plant vegetables or perform religious rituals on their roofs. Ground floors would be used to for shops, workshops, storage, and livestock. One room was usually a sanctuary.

가구

Furniture

고대 수메르에서, 주택에는 정교하게 장식된 스툴, 의자, 항아리, 욕조가 있었다. 부유한 시민들은 변기와 적절한 배수 시스템을 갖추고 있었다. 일부 주택에는 중앙에 제단이 있었을 가능성이 있다. 이 제단은 신들에게 바쳐졌을 수도 있지만, 중요한 사람들에게 헌정되었을 수도 있다.

In ancient Sumer, houses contained elaborately decorated stools, chairs, jars, and bathtubs. Wealthier citizens had toilets and proper drainage systems. It is possible some houses had altars in the center of the houses. These altars could have been dedicated to the gods, but they could have been dedicated to important people.

궁전

Palaces

궁전은 왕조 1기(우르크 제1왕조) 초기에 존재하기 시작했다. 처음에는 소박했던 궁전은 권력이 점점 중앙집권화됨에 따라 그 규모와 복잡성이 커진다. 이 궁전은 루갈이나 엔시가 거주하고 일하던 ‘큰 집'(설형문자 E2.GAL, 수메르어 e2-gal, 아카드어: ekallu)이라고 불렀다.

The palace came into existence during the Early Dynastic I period. From a rather modest beginning the palace grows in size and complexity as power is increasingly centralized. The palace is called a ‘Big House’ (Cuneiform: E2.GAL Sumerian e2-gal Akkdian: ekallu) where the lugal or ensi lived and worked.

초기 메소포타미아 핵심 계층의 궁전은 대규모 단지였으며, 종종 호화롭게 장식되었다. 가장 초기에 알려진 사례는 카파자 및 텔 아스마르와 같은 디얄라 강 계곡 유적지들이다. 이 기원전 3000년대의 궁전은 대규모 사회경제적 기관으로 기능했기 때문에, 주거 및 사적 기능과 함께 장인의 작업장, 식품 창고, 의식용 안뜰을 수용했으며, 종종 사당과 연관되었다. 예를 들어, 난나(달의 신)의 여사제들이 거주했던 우르의 “기파루”는 여러 안뜰, 여러 성역, 죽은 여사제들을 위한 묘실, 의식 연회장 등이 있는 대규모 단지였다. 이와 비슷하게 복잡한 메소포타미아 궁전의 사례가 시리아의 마리에서 발굴되었는데, 그 연대는 고대 바빌로니아 시대로 거슬러 올라간다.

The palaces of the early Mesopotamian elites were large-scale complexes, and were often lavishly decorated. Earliest known examples are from the Diyala River valley sites such as Khafajah and Tell Asmar. These third millennium BC palaces functioned as large-scale socio-economic institutions, and therefore, along with residential and private functions, they housed craftsmen workshops, food storehouses, ceremonial courtyards, and are often associated with shrines. For instance, the so-called “giparu” (Sumerian: e₂gi₆-par₄-ku₃) at Ur where the Moon god Nanna’s priestesses resided was a major complex with multiple courtyards, a number of sanctuaries, burial chambers for dead priestesses, and a ceremonial banquet hall. A similarly complex example of a Mesopotamian palace was excavated at Mari in Syria, dating from the Old Babylonian period.

특히 칼후/님루드, 두르 샤르루킨/코르샤바드, 니느웨/니네베에 있는 철기 시대의 아시리아 궁전들은 모두 오르토스타트라고 불리는 석판에 새겨진 아시리아 궁전 부조와 벽에 새겨진 광범위한 그림 및 문자로 된 서사 프로그램으로 유명해졌다. 이 회화 프로그램에는 컬트적인 장면 혹은 왕의 군대와 시민의 업적에 대한 서술적 설명이 포함되어 있다. 성문과 중요한 통로 옆에는 액막이용 신화적 인물, 라마수, 날개 달린 지니의 거대한 석조 조각이 나란히 놓여 있었다. 이 철기 시대 궁전의 건축적 배치 또한 크고 작은 안뜰을 중심으로 조직되었다. 보통 왕의 공식 알현실은 중요한 국무회의가 열리고 국가 의식(행사)이 거행되는 거대한 의식용 안뜰로 개방되어 있었다.

Assyrian palaces of the Iron Age, especially at Kalhu/Nimrud, Dur Sharrukin/Khorsabad and Ninuwa/Nineveh, have become famous due to the Assyrian palace reliefs, extensive pictorial and textual narrative programs on their walls, all carved on stone slabs known as orthostats. These pictorial programs either incorporated cultic scenes or the narrative accounts of the kings’ military and civic accomplishments. Gates and important passageways were flanked with massive stone sculptures of apotropaic mythological figures, lamassu and winged genies. The architectural arrangement of these Iron Age palaces were also organized around large and small courtyards. Usually the king’s throne room opened to a massive ceremonial courtyard where important state councils met and state ceremonies were performed.

아시리아 궁전 일부에서는 당시 북부 시리아 네오-히타이트 국가들과의 활발한 무역 관계를 보여주는 엄청난 양의 상아 가구 조각이 발견되었다. 청동 양각 기법의 밴드는 주요 건물들의 나무 문을 장식했지만, 제국이 몰락할 때 대부분 약탈당했다; 발라왓 문이 주요하게 남아 있는 유물이다.

Massive amounts of ivory furniture pieces were found in some Assyrian palaces pointing to an intense trade relationship with North Syrian Neo-Hittite states at the time. Bronze repousse bands decorated the wooden gates of major buildings, but were mostly looted at the fall of the empire; the Balawat Gates are the principal survivors.

사원

Temples

사원은 종종 도시 정착지가 만들어지기 전부터 존재했으며, 수메르 역사 2,500년에 걸쳐 작은 원룸 구조에서 1 에이커 이상의 정교한 단지로 발달했다. 수메르의 사원, 요새, 궁전은 부벽, 벽감, 반(쪽) 기둥과 같은 고급 재료와 기법이 사용되었다. 연대기적으로, 수메르 사원은 초기 우바이드 사원으로부터 진화했다. 성전이 노후함에 따라 의식적으로 파괴되었고 그 기초 위에 새 사원이 세워졌다. 후임 사원은 전임 사원보다 더 크고 더 명확하게 지어졌다. 에리두에 있는 에압주 사원의 진화는 이 과정에서 자주 인용되는 사례다. 많은 사원들에 텔 우카이르의 사원과 같은 비문이 새겨져 있었다. 궁전과 도시 성벽은 초기 왕조 시대의 사원보다 훨씬 늦게 나타났다.

Temples often predated the creation of the urban settlement and grew from small one room structures to elaborate multiacre complexes across the 2,500 years of Sumerian history. Sumerian temples, fortifications, and palaces made use of more advanced materials and techniques, such as buttresses, recesses, and half columns. Chronologically, Sumerian temples evolved from earlier Ubaid temples. As the temple decayed it was ritually destroyed and a new temple built on its foundations. The successor temple was larger and more articulated than its predecessor temple. The evolution of the E2.abzu temple at Eridu is a frequently cited case-study of this process. Many temples had inscriptions engraved into them, such as the one at Tell Uqair. Palaces and city walls came much later after temples in the Early Dynastic Period.

수메르 사원의 형태는 세계를 바다로 둘러싸인 땅의 원반으로 묘사한 근동 우주론의 구현으로, 이 모든 것이 압수라고 불리는 또 다른 민물 바다 위에 떠 있었고 그 위에는 시간을 조절하는 반구형의 궁창이 있었다. 세계-산은 세 개의 레이어를 모두 연결하는 악시스 문디(세계-축)를 형성했다. 사원의 역할은 신과 인간의 만남의 장소인 악시스 문디로서의 역할을 하는 것이었다. 영역 간 만남의 지점으로서 ‘산당(山堂)’의 신성불가침은 신석기 시대 근동 지역에서 입증된 우바이드-이전의 믿음이었다. 사원의 평면은 산에서 네 개의 대륙으로 흐르는 네 개의 강을 상징하기 위해 모서리들이 기본 방위를 가리키는 직사각형이었다. 이 방위는 또한 사원 지붕을 수메르인들의 시간 측정을 위한 관측소로 사용하는 실용적인 목적에도 부합한다. 이 사원은 창조 당시 물에서 솟아난 태고적 땅의 신성한 둔덕인 ‘순수한 둔덕”(수메르어: du6-ku3 설형문자:?)을 의미하는 두쿠그를 나타내기 위해 다져진 흙의 낮은 테라스 위에 지어졌다.

The form of a Sumerian temple is manifestation of Near Eastern cosmology, which described the world as a disc of land which was surrounded by a salt water ocean, both of which floated on another sea of fresh water called apsu, above them was a hemispherical firmament which regulated time. A world mountain formed an axis mundi that joined all three layers. The role of the temple was to act as that axis mundi, a meeting place between gods and men. The sacredness of ‘high places’ as a meeting point between realms is a pre-Ubaid belief well attested in the Near East back the Neolithic age. The plan of the temple was rectangular with the corners pointing in cardinal directions to symbolize the four rivers which flow from the mountain to the four world regions. The orientation also serves a more practical purpose of using the temple roof as an observatory for Sumerian timekeeping. The temple was built on a low terrace of rammed earth meant to represent the sacred mound of primordial land which emerged from the water called dukug, ‘pure mound’ (Sumerian: du6-ku3 Cuneiform:) during creation.

긴 축의 문은 신들의 진입점이고, 짧은 축의 문은 인간의 진입점이었다. 이 구성은 중앙 홀 끝에 있는 이교도 신상을 마주하기 위해 90도로 회전해야 했기 때문에 ‘구부러진 축 접근법’이라고 불렀다.

The doors of the long axis were the entry point for the gods, and the doors of the short axis the entry point for men. This configuration was called the bent axis approach, as anyone entering would make a ninety degree turn to face the cult statue at the end of the central hall.

구부러진 축 접근법은 선형 축 접근법을 사용했던 우바이드 사원으로부터의 혁신이며, 수메르 주택의 특징이기도 하다. 축의 교차점에 있는 사원의 중앙에 (신께 바치는) 제물상이 놓여 있었다.

The bent axis approach is an innovation from the Ubaid temples which had a linear axis approach, and is also a feature of Sumerian houses. An offering table was located in the centre of the temple at the intersection of the axes.

우루크 시대의 사원들은 사원의 직사각형을 세 갈래 평면으로, T-형 평면으로 또는 (이 둘의) 결합 평면으로 나누었다. 우바이드로부터 계승된 세 갈래 평면은 양쪽에 두 개의 작은 측면 홀이 있는 큰 중앙 홀을 가지고 있었다. 입구는 짧은 축을 따라 있었고, 사당은 긴 축의 끝에 있었다. 우바이드 시대의 T-자형 평면 역시 본당에 수직인 직사각형의 한쪽 끝에 있는 홀을 제외하고는 세 갈래 평면과 동일했다. 우르크의 에안나 지구에 있는 C 사원은 고전 사원 형태의 사례다.

Temples of the Uruk Period divided the temple rectangle into tripartite, T-shaped, or combined plans. The tripartite plan inherited from the Ubaid had a large central hall with two smaller flanking halls on either side. The entry was along the short axis and the shrine was at the end of the long axis. The T-shaped plan, also from the Ubaid period, was identical to the tripartite plan except for a hall at one end of the rectangle perpendicular to the main hall. Temple C from the Eanna district of Uruk is a case-study of classical temple form.

초기 왕조에 이어지는 기간 동안 사원 디자인의 다양성이 폭발적으로 증가했다. 이 사원들은 여전히 기본 방위, 직사각형 평면, 부벽과 같은 특징을 유지했다. 그러나 이제 그것들은 안뜰, 벽, 분지, 막사를 포함한 다양한 새로운 구성을 취했다. (디얄라 강 유역에 있는) 카파자에 있는 신(Sin) 사원은 이 시대의 전형으로, 셀라(신상 안치소)로 이어지는 일련의 안뜰을 중심으로 디자인되었다.

There was an explosion of diversity in temple design during the following Early Dynastic Period. The temples still retained features such as cardinal orientation, rectangular plans, and buttresses. Now however they took on a variety new configurations including courtyards, walls, basins, and barracks. The Sin Temple in Khafajah is typical of this era, as it was designed around a series of courtyards leading to a cella.

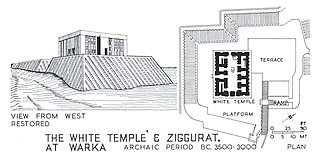

하이 템플은 도시의 수호신이 모셔진 특별한 유형의 사원이었다. 기능적으로, 성직자를 수용하는 것은 물론 저장 및 분배 센터 역할을 했다. 우루크에 있는 아누의 백색사원은 어도비 벽돌의 기단 위에 매우 높게 지어진 하이 템플의 전형이다. 초기 왕조 시대에 하이 템플은 계단식 피라미드를 만드는 일련의 기단인 지구라트가 포함되기 시작했다. 그러한 지구라트는 성경의 바벨탑에 영감을 주었을 수도 있다.

The high temple was a special type of temple that was home to the patron god of the city. Functionally, it served as a storage and distribution centre as well as housing the priesthood. The White Temple of Anu in Uruk is typical of a high temple which was built very high on a platform of adobe-brick. In the Early Dynastic period high temples began to include a ziggurat, a series of platforms creating a stepped pyramid. Such ziggurats may have been the inspiration for the Biblical Tower of Babel.

지구라트

Ziggurats

지구라트는 수메르 도시-국가에서 처음 지어진 후 바빌로니아와 아시리아 도시에서도 발전한 거대한 피라미드식 사원 탑이었다. 메소포타미아 또는 그 근처에는 이라크 28개, 이란 4개 등 총 32개의 지구라트가 알려져 있다. 주목할만한 지구라트로는 이라크 나시리야 인근 우르의 그레이트 지구라트, 이라크 바그다드 인근 아카르 쿠프의 지구라트, 이란의 후제스탄에 있는 초하 잔빌 지구라트(가장 최근에 발견된 것), 이란의 카샨 인근 시알크 지구라트 등이 있다. 지구라트는 수메르인, 바빌로니아인, 엘람인, 아시리아인이 지역 종교의 기념물로 지었다. 지구라트의 가장 초기 사례는 기원전 4000년대 우바이드 시대의 기단이며, 가장 최근의 것은 기원전 6세기에 세워진 것이다. 지구라트의 꼭대기는 많은 피라미드들과 달리 평평했다. 계단식 피라미드 양식은 초기 왕조 시대가 끝날 무렵 시작되었다.

Ziggurats were huge pyramidal temple towers which were first built in Sumerian City-States and then developed in Babylonia and Assyrian cities as well. There are 32 ziggurats known at, or near, Mesopotamia—28 in Iraq and 4 in Iran. Notable ziggurats include the Great Ziggurat of Ur near Nasiriyah, Iraq, the Ziggurat of Aqar Quf near Baghdad, Iraq, Chogha Zanbil in Khūzestān, Iran (the most recent to be discovered), and the Sialk near Kashan, Iran. Ziggurats were built by the Sumerians, Babylonians, Elamites, and Assyrians as monuments to local religions. The earliest examples of the ziggurat were raised platforms that date from the Ubaid period during the fourth millennium BC, and the latest date from the 6th century BC. The top of the ziggurat was flat, unlike many pyramids. The step pyramid style began near the end of the Early Dynastic Period.

직사각형, 타원형 또는 정사각형 기단 위에 후퇴하는 단으로 지어진 지구라트는 피라미드식 구조였다. 햇볕에 구운 벽돌이 지구라트의 코어를 구성하고, 외부는 구운 벽돌로 마감했다. 그 면들은 종종 다른 색깔로 유약을 칠했으며, 점성술적인 의미가 있었을지도 모른다. 왕들은 가끔 이 오지벽돌(찰흙으로 일정한 형을 만들어 오지물을 칠해 구운 벽돌)에 그들의 이름을 새기기도 했다. 층수는 2~7층까지 다양했으며, 정상에는 사당이나 사원이 있었다. 사당으로의 접근은 지구라트 한쪽에 있는 일련의 경사로 또는 바닥에서 정상까지 나선형 경사로를 통해 이루어졌다. 지구라트는 산을 닮도록 지어졌다는 가설이 제기되었지만, 그 가설을 뒷받침할 문헌이나 고고학적 증거는 거의 없다.

Built in receding tiers upon a rectangular, oval, or square platform, the ziggurat was a pyramidal structure. Sun-baked bricks made up the core of the ziggurat with facings of fired bricks on the outside. The facings were often glazed in different colours and may have had astrological significance. Kings sometimes had their names engraved on these glazed bricks. The number of tiers ranged from two to seven, with a shrine or temple at the summit. Access to the shrine was provided by a series of ramps on one side of the ziggurat or by a spiral ramp from base to summit. It has been suggested that ziggurats were built to resemble mountains, but there is little textual or archaeological evidence to support that hypothesis.

고전적인 지구라트는 네오-수메르 시대에 관절로 연결된 부벽, 유리 같은 벽돌 피복, 입면에서의 배흘림(엔타시스)과 함께 출현했다. 우르의 지구라트가 이 양식의 가장 좋은 사례다. 이 시기 사원 디자인의 또 다른 변화는 사원에 대한 구부러진 축 접근 방식과 반대되는 선형 축 접근 방식이었다.

Classical ziggurats emerged in the Neo-Sumerian Period with articulated buttresses, vitreous brick sheathing, and entasis in the elevation. The Ziggurat of Ur is the best example of this style. Another change in temple design in this period was a straight as opposed to bent-axis approach to the temple.

우르에 있는 우르-남무1 지구라트는 3단계 시공으로 디자인되었으나 오늘날에는 이들 중 두 단계만 남아 있다. 이 전체 진흙벽돌의 코어 구조는 원래 역청으로 설정된 구운 벽돌의 외피로 둘러싸여 있었으며, 가장 낮은 첫 번째 단계에서 2.5m, 두 번째 단계에서 1.15m 높이로 되어 있었다. 이들 구운 벽돌에는 각각 왕의 이름이 찍혀 있었다. 단(계)의 경사벽이 버팀목이 되어 있었다. 정상에로의 접근은 3개의 기념비적인 계단을 통해 이루어졌는데, 모두 첫 번째 단과 두 번째 단 사이의 층계참에서 열리는 포털2에서 수렴된다. 첫 번째 단 높이는 약 11m, 두 번째 단 높이는 약 5.7m 올라갔다. 흔히 세 번째 단은 지구라트의 발굴자(레나드 울리)에 의해 재건되었고, 그 위에 사원이 세워졌다. 초하 잔빌 지구라트에서 고고학자들은 지구라트 구조의 코어를 가로지르며 진흙벽돌 덩어리를 한데 묶은 거대한 갈대 밧줄을 발견했다.

Ur-Nammu’s ziggurat at Ur was designed as a three-stage construction, but today only two of these survive. This entire mudbrick core structure was originally given a facing of baked brick envelope set in bitumen, 2.5 m on the first lowest stage, and 1.15 m on the second. Each of these baked bricks were stamped with the name of the king. The sloping walls of the stages were buttressed. The access to the top was by means of a triple monumental staircase, which all converges at a portal that opened on a landing between the first and second stages. The height of the first stage was about 11 m while the second stage rose some 5.7 m. Usually, a third stage is reconstructed by the excavator of the ziggurat (Leonard Woolley), and crowned by a temple. At the Chogha Zanbil ziggurat, archaeologists have found massive reed ropes that ran across the core of the ziggurat structure and tied together the mudbrick mass.

초기 메소포타미아에서 가장 주목할만한 건축 유적은 기원전 4,000년의 우르크 사원 단지, 카파제 및 텔 아스마르 등 디얄라 강 계곡의 초기 왕조 시대 유적지의 사원과 궁전, 니푸르와 우르(난나의 안식처)에 있는 우르 제3왕조의 유적, 에블라, 마리, 알랄라흐, 알레포, 쿨테베의 시리아-터키 사이트에 있는 중기 청동기 시대 유적, 보고즈코이(하투샤), 우가리트, 아슈르와 누지에 있는 후기 청동기 시대 궁전, 아시리아(칼후/님루드, 코르사바드, 니네베), 바빌로니아(바빌론), 우라르투(투쉬파/반, Haykaberd, 아야니스, 아르마비르, 에레부니, 바스탐) 그리고 네오-히타이트 사이트(카르카미스, 텔 할라프, 카라테페)에 있는 철기 시대 궁전이 있다. 집들은 대부분 니푸르와 우르에 있는 올드 바빌로니아 유적에서 알려져 있다. 건물의 건설과 관련 의례에 관한 문헌 자료 중에는 기원전 3,000년 후반의 구데아 원통들과 철기 시대의 아시리아 및 바빌로니아 왕실 비문들이 주목할 만하다.

The most notable architectural remains from early Mesopotamia are the temple complexes at Uruk from the 4th millennium BC, temples and palaces from the Early Dynastic period sites in the Diyala River valley such as Khafajah and Tell Asmar, the Third Dynasty of Ur remains at Nippur (Sanctuary of Enlil) and Ur (Sanctuary of Nanna), Middle Bronze Age remains at Syrian-Turkish sites of Ebla, Mari, Alalakh, Aleppo and Kultepe, Late Bronze Age palaces at Bogazkoy (Hattusha), Ugarit, Ashur and Nuzi, Iron Age palaces and temples at Assyrian (Kalhu/Nimrud, Khorsabad, Nineveh), Babylonian (Babylon), Urartian (Tushpa/Van, Haykaberd, Ayanis, Armavir, Erebuni, Bastam) and Neo-Hittite sites (Karkamis, Tell Halaf, Karatepe). Houses are mostly known from Old Babylonian remains at Nippur and Ur. Among the textual sources on building construction and associated rituals are Gudea’s cylinders from the late 3rd millennium are notable, as well as the Assyrian and Babylonian royal inscriptions from the Iron Age.

아시리아 건물, 요새, 사원 디자인

Design of Assyrian buildings, fortifications and temples

모든 아시리아 건물의 평면은 직사각형이며, 우리는 오래 전에 동양 건축가들이 거의 변함없이 이 윤곽을 사용했고, 그 위에 지금까지 고안된 가장 매력적이고 다양한 형태를 키워왔음을 알고 있다. 그것들은 우아한 곡선으로 각도를 넘나들며 모이고, 평범한 사각 홀의 기반 위에 미나렛(이슬람 사원의 뾰족탑)이나 돔, 팔각형 또는 원을 연장하여 짓는다. 아시리아에서 이런 일들이 때때로 이루어졌다는 것은 조각품을 통해 알 수 있다. 쿠윤직(니느웨)의 석판들은 다양한 형태의 돔과 탑 같은 구조물을 보여주며, 각각 사각형 바닥에서 솟아 있다. 돔의 고대 형태와 아시리아 마을에서 여전히 사용되는 것의 유사성은 매우 놀랍다. 경사진 지붕이 사용됐는지 여부는 불확실하다. Mr. Bonomi(Joseph Bonomi?)는 그들이 그렇게 했다고 믿고 있으며, 몇 개의 조각품들이 그의 견해를 뒷받침하는 것 같다. 물론 민가에는 아무것도 남아 있지 않다; 그러나 그들은 여러 층의 높이로 석판 위에 표현했으며 1층은 창문 없이 문만 있는 게 보통이다. 모든 집은 평평한 지붕을 가지고 있고, 불타는 마을을 표현한 부조 중 하나에서 알 수 있듯이 이러한 지붕은 지금처럼 튼튼한 대들보 위에 두꺼운 흙 층을 쌓아 만들었다. 이 지붕은 거의 내화성이 있으며, 지붕에 의해 멈춘 화염은 창문으로 나오는 것으로 표현된다. 우리가 아는 한, 창문이나 내부 계단의 잔해는 아직 발견되지 않았다.

The plans of all the Assyrian buildings are rectangular, and we know that long ago, as now, the Eastern architects used this outline almost invariably, and upon it reared some of the most lovely and varied forms ever devised. They gather over the angles by graceful curves, and on the basis of an ordinary square hall carry up a minaret or a dome, an octagon or a circle. That this was sometimes done in Assyria is shown by the sculptures. Slabs from Kouyunjik show domes of varied form, and tower-like structures, each rising from a square base. The resemblance between the ancient form of the dome and those still used in the Assyrian villages is very striking. Whether sloping roofs were used is uncertain. Mr. Bonomi believes that they were, and a few sculptures seem to support his view. Of the private houses nothing, of course, remains; but they are represented on the slabs as being of several stories in height, the ground floor as usual having only a door and no windows. All have flat roofs, and we gather from one of the bas-reliefs, which represents a town on fire, that these roofs were made, just as they now are, with thick layers of earth on strong beams. These roofs are well-nigh fireproof, and the flames are represented as stopped by them, and coming out of the windows. No remains of a window, or, so far as we are aware, of an internal staircase, have been found.

요새화에 대해 우리는 훨씬 더 많이 알고 있다. 님루드의 북쪽 벽에는 58개의 탑의 흔적이 발견되었고, 쿠윤직에는 3개의 벽으로 된 큰 유적이 있는데 하부는 돌로 되어 있고 상부는 햇볕에 말린 벽돌로 되어 있다. 코르사바드에는 아직도 3~4피트(1.2m) 두께의 돌 블록으로 지은 40피트(12m) 높이의 성벽 유적이 남아 있으며, 이 벽의 마감에 대한 증거는 같은 종류의 중세 작품과 매우 흡사한 조각품들에 의해 완전히 제공되고 있다. 중앙에 거대한 탑이나 성채가 있는 여러 층의 벽이 표현되어 있다. 입구는 사각형 탑들이 측면에 있는 아치형 관문이다. 이 탑들과 다른 탑들은 중세의 석락처럼 돌출된 난간을 가지고 있고 흉벽으로 마무리되었으며, 그 유적은 님루드와 쿠윤직, 그리고 니네베 이전의 아시리아 수도인 아슈르에서 발견되었다.

Of the fortifications we know much more. In the north wall of Nimroud fifty-eight towers have been traced, and at Kouyunjik there are large remains of three walls, the lower part being of stone, and the upper of sun-dried bricks. At Khorsabad there are the remains of a wall, still 40 feet (12 m) high, built of blocks of stone 3 to 4 feet (1.2 m) thick, and the evidences wanting as to finishing of these is completely supplied by the sculptures, which show an extraordinary resemblance to medieval works of the same class. Tier upon tier of walls are represented, enclosing a great tower or keep in the centre. The entrances are great arched gateways flanked by square towers. These and the other towers have overhanging parapets just like the mediaeval machicolations, and are finished at top with battlements, remains of which have been found at Nimrud and Kouyunjik, and at Assur, the capital of Assyria before Nineveh.

궁전과 구별되는 사원의 경우 몇몇 유적이 남아 있는 것으로 추정되지만, 그것들의 일반적인 형태에 대해서는 확실하게 알려진 것이 거의 없다.

Of temples distinct from the palace we have a few supposed remains, but little is absolutely known as to their general form.

그러나 칼데아에는 사원의 하부 구조를 형성한 광대한 마운드가 있는 거대한 잔해가 남아 있다. 이 모든 것 중 가장 웅장하고 흥미로운 것은 일곱 구체의 사원으로 확인된, 바빌론 근처 보르시파(현재의 비르스 님로드)에 있는 나부의 사원이다. 이것은 잘 알려진 비문으로 나타난 것처럼 네브카드네자르(신 바빌로니아 왕, BC 605~562)에 의해 재건되었다. 또 다른 사례는 무그하일에 있는데, 바닥이 198피트(60m) x 133피트(41m)이고 지금도 70피트(21m) 높이에 달하며, 그것과 비르스 모두 단계가 줄어들면서 일련의 웅장한 기단을 보여주며 오를수록 길이가 줄어들고 사원 수도실을 위해 상단에 비교적 작은 기단을 남기는 방식으로 지어졌음이 분명하다. (여기에 사용된 것은) 고대 오븐에서 제조된 도화벽돌로 추정되며, 비루스 님루드에서 발견되었다.

But in Chaldea there are some enormous masses of ruins, evidently remains of the vast mounds which formed the substructure of their temples. The grandest of all these and the most interesting is the temple of Nabû at Borsippa (now Birs Nimrod), near Babylon, which has been identified as the temple of the Seven Spheres. This was reconstructed by Nebuchadnezzar, as appears by a well-known inscription. Another example is at Mugheir, which was 198 feet (60 m) by 133 feet (41 m) at the base, and is even now 70 feet (21 m) high, and it is clear that both it and the Birs were built with diminishing stages, presenting a series of grand platforms, decreasing in length as they ascended, and leaving a comparatively small one at top for the temple cell. This has been found, it is supposed, at the Birs Nimroud, of vitrified brick made in ancient ovens.

조경

Landscape architecture

문헌 자료에 따르면 오픈스페이스 계획이 초기부터 도시의 일부였음을 알 수 있다. 길가메시 서사시의 우루크에 대한 묘사는 도시의 ⅓을 과수원으로 지정해 놓았음을 말해준다. 니푸르의 인클로저 ⅕에서도 유사하게 계획된 오픈스페이스가 발견된다. 또 다른 중요한 경관 요소는 공터(아카드어: kišubbû)였다.

Text sources indicate open space planning was a part of the city from the earliest times. The description of Uruk in the Epic of Gilgamesh tells of one third of that city set aside for orchards. Similar planned open space is found at the one fifth enclosure of Nippur. Another important landscape element was the vacant lot (Akkadian: kišubbû).

도시 외곽에서, 수메르인들의 관개농업은 역사상 최초의 정원 형태를 만들었다. 정원(sar)은 144평방-큐빗으로 둘레에 운하가 있었다. 닫힌 사각형의 이러한 형태는 이후 페르시아의 ‘파라다이스 가든’의 기초가 되었다.

External to the city, Sumerian irrigation agriculture created some of the first garden forms in history. The garden (sar) was 144 square cubits with a perimeter canal. This form of the enclosed quadrangle was the basis for the later paradise gardens of Persia.

메소포타미아에서, 분수의 사용은 기원전 3,000년까지 거슬러 올라간다. 초기 사례는 라가시 중심부 기르수에서 발견된 기원전 3,000년경의 바빌로니아 조각 분지에 보존되어 있다. 고대 아시리아 분수는 “코멜 강 협곡에서 발견되었으며, 단단한 암석을 깎아 만든 분지들로 이루어져 있으며 계단식으로 하천으로 내려간다.” 물은 작은 도관에서 유도되었다.

In Mesopotamia, the use of fountains date as far back as the 3rd millennium BC. An early example is preserved in a carved Babylonian basin, dating back to ca. 3000 B.C., found at Girsu, Lagash. An ancient Assyrian fountain “discovered in the gorge of the Comel River consists of basins cut in solid rock and descending in steps to the stream.” The water was led from small conduits.

- 출처 : 「Architecture of Mesopotamia」, Wikipedia(en), 2020.12.6.