Colonialism

콜로니얼리즘(식민주의)은 외국 집단이 사람들과 자원을 착취하는 것을 의미한다. 콜로나이저(식민지 개척자, 이주종)는 정치적 권력을 독점하며, 정복당한 사회와 그 구성원을 법적, 행정적, 사회적, 문화적, 또는 생물학적 측면에서 자신들보다 열등한 존재로 간주한다. 콜로니얼리즘은 흔히 제국주의 체제로 발전하는 경우가 많지만, 식민 정착민들이 영토를 침략하고 점령하여 기존 사회를 식민지 개척자들의 사회로 영구히 대체하고 원주민에 대한 집단학살(제노사이드)을 목표로 하는 정착형 식민주의의 형태로도 나타날 수 있다.

Colonialism is the exploitation of people and of resources by a foreign group. Colonizers monopolize political power and hold conquered societies and their people to be inferior to their conquerors in legal, administrative, social, cultural, or biological terms. While frequently advanced as an imperialist regime, colonialism can also take the form of settler colonialism, whereby colonial settlers invade and occupy territory to permanently replace an existing society with that of the colonizers, possibly towards a genocide of native populations.

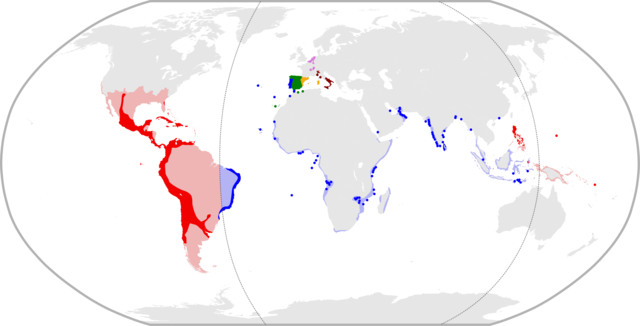

콜로니얼리즘은 15세기부터 20세기 중반까지 전 세계적으로 확산된 근대 시기의 유럽 식민 제국을 설명하는 개념으로 발전했다. (1800년까지 지구 육지의 35%를 차지했고 제1차 세계대전이 시작될 무렵에는 84%로 정점을 찍었다.) 유럽의 콜로니얼리즘은 중상주의와 특허회사를 활용했으며, 성, 젠더, 인종, 장애, 계급 등에 대한 근대의 생명정치를 통해 식민지화된 사람들을 사회-경제적으로 타자화 하고 하위 주체(서발턴)로 유지하여 교차 폭력과 차별을 낳는 식민성을 확립했다. 콜로니얼리즘은 토지와 생명을 개간하고 발전시킨다는 문명화 사명의 신념을 바탕으로 정당화되었으며, 이는 역사적으로 기독교적 사명을 믿는 신념에 뿌리를 두고 있는 경우가 많았다.

Colonialism developed as a concept describing European colonial empires of the modern era, which spread globally from the 15th century to the mid-20th century, spanning 35% of Earth’s land by 1800 and peaking at 84% by the beginning of World War I. European colonialism employed mercantilism and chartered companies, and established coloniality, which keeps the colonized socio-economically othered and subaltern through modern biopolitics of sexuality, gender, race, disability and class, among others, resulting in intersectional violence and discrimination. Colonialism has been justified with beliefs of having a civilizing mission to cultivate land and life, based on beliefs of entitlement and superiority, historically often rooted in the belief of a Christian mission.

이러한 광범위한 영향으로 인해 전 세계와 역사 속에서 다양한 콜로니얼리즘의 사례들이 확인되었는데, 이는 콜로니(식민지)와 메트로폴(전체 식민지 제국에 대하여 권력을 행사하는 유럽 본국 영토)이 발전하면서 식민지 분리와 특성이 확립된 때부터 시작되었다.

Because of this broad impact different instances of colonialism have been identified from around the world and in history, starting with when colonization was developed by developing colonies and metropoles, the base colonial separation and characteristic.

18세기에 시작된 디콜로나이제이션(탈식민화)은 특히 1945년에서 1975년 사이 제2차 세계대전의 여파로 일어난 대규모 탈식민화와 더불어 점차 식민지 독립의 물결로 이어졌다. 식민지 제도의 변화가 경제 발전, 정권 유형, 국가 역량의 차이를 설명할 수 있다는 것을 학자들이 보여주었듯이, 콜로니얼리즘은 현대 사회의 다양한 결과에 지속적인 영향을 미친다. 일부 학자들은 현대에 간접적인 방식으로 식민 지배의 요소가 계속되거나 부과되는 현상을 설명하기 위해 네오콜로니얼리즘(신식민주의)이라는 용어를 사용하기도 했다.

Decolonization, which started in the 18th century, gradually led to the independence of colonies in waves, with a particular large wave of decolonizations happening in the aftermath of World War II between 1945 and 1975. Colonialism has a persistent impact on a wide range of modern outcomes, as scholars have shown that variations in colonial institutions can account for variations in economic development, regime types, and state capacity. Some academics have used the term neocolonialism to describe the continuation or imposition of elements of colonial rule through indirect means in the contemporary period.

어원

Etymology

콜로니얼리즘은 어원적으로 로마 제국의 소작인을 지칭하는 라틴어 ‘콜로누스’에 뿌리를 두고 있다. 콜로누스 소작인은 (처음에는) 지주의 소작인으로 시작했지만, 제도가 발전하면서 지주에게 영구적으로 빚을 지게 되고 노예로 전락했다.

Colonialism is etymologically rooted in the Latin word “Colonus”, which was used to describe tenant farmers in the Roman Empire. The coloni sharecroppers started as tenants of landlords, but as the system evolved they became permanently indebted to the landowner and trapped in servitude.

정의

Definitions

콜로니얼리즘이라는 말이 사용된 초기에는 인간이 이주하여 정착한 농장을 지칭했다. 이 용어는 20세기 초에 이르러 유럽 제국의 팽창 그리고 아시아 및 아프리카 민족의 제국주의적 예속을 지칭하는 말로 그 의미가 확대되었다.

The earliest uses of colonialism referred to plantations that men emigrated to and settled. The term expanded its meaning in the early 20th century to primarily refer to European imperial expansion and the imperial subjection of Asian and African peoples.

『콜린스 영어 사전』은 콜로니얼리즘을 “강대국이 약소국을 직접 통제하고 그들의 자원을 이용해 자국의 권력과 부를 증대시키는 관행”이라고 정의한다. 『웹스터 백과사전』은 식민주의를 “한 국가가 다른 민족이나 영토에 대한 권위를 확장하거나 유지하려는 체제 또는 정책”이라고 정의한다. 『메리엄-웹스터 사전』은 콜로니얼리즘에 대해 네 가지 정의를 제공하며, 여기에는 “식민지의 특징적인 것”과 “한 권력이 종속된 지역이나 사람들을 지배하는 것”이 포함된다.

Collins English Dictionary defines colonialism as “the practice by which a powerful country directly controls less powerful countries and uses their resources to increase its own power and wealth”. Webster’s Encyclopedic Dictionary defines colonialism as “the system or policy of a nation seeking to extend or retain its authority over other people or territories”. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary offers four definitions, including “something characteristic of a colony” and “control by one power over a dependent area or people”.

『스탠퍼드 철학 백과사전』은 “아메리카, 오스트레일리아, 아프리카 및 아시아 일부를 포함한 세계 다른 지역에 대한 유럽의 정착 및 정치적 통제 과정을 설명하기 위해” 콜로니얼리즘이라는 용어를 사용한다. 그것은 식민주의, 제국주의, 정복의 차이를 논하며 “식민주의를 정의하는 데 어려움이 따르는 이유는 이 용어가 종종 제국주의와 동의어로 사용되기 때문이다. 식민주의와 제국주의 모두 유럽에 경제적, 전략적 이익을 제공할 것으로 기대되는 정복의 형태였다”고 설명하며, 이어서 “두 용어를 일관되게 구분하기 어려운 점을 감안하여, 이 항목에서는 콜로니얼리즘을 1960년대 민족해방운동으로 끝난 16세기부터 20세기까지 유럽의 정치적 지배 프로젝트를 가리키는 넓은 의미로 사용하기로 한다”고 덧붙인다.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy uses the term “to describe the process of European settlement and political control over the rest of the world, including the Americas, Australia, and parts of Africa and Asia”. It discusses the distinction between colonialism, imperialism and conquest and states that “[t]he difficulty of defining colonialism stems from the fact that the term is often used as a synonym for imperialism. Both colonialism and imperialism were forms of conquest that were expected to benefit Europe economically and strategically,” and continues “given the difficulty of consistently distinguishing between the two terms, this entry will use colonialism broadly to refer to the project of European political domination from the sixteenth to the twentieth centuries that ended with the national liberation movements of the 1960s”.

위르겐 오스터함멜(1952-)의 『식민주의: 이론적 개관』 서문에서 로저 티그너는 이렇게 말한다. “오스터함멜에게 있어 식민주의의 본질은 식민지의 존재에 있으며, 식민지는 정의상 보호령이나 비공식적인 영향권 같은 다른 영토와는 다르게 통치되는 곳이다.” 오스터하멜은 자신의 책에 “어떻게 ‘식민주의’를 ‘식민지’와 독립적으로 정의할 수 있는가?”라고 묻는다. 그는 다음의 세 문장으로 정의를 내린다:

In his preface to Jürgen Osterhammel’s Colonialism: A Theoretical Overview, Roger Tignor says “For Osterhammel, the essence of colonialism is the existence of colonies, which are by definition governed differently from other territories such as protectorates or informal spheres of influence.” In the book, Osterhammel asks, “How can ‘colonialism’ be defined independently from ‘colony?’” He settles on a three-sentence definition:

콜로니얼리즘은 원주민(또는 강제로 이주된) 다수와 외국에서 침략해 온 소수 간의 관계이다. 피식민지 주민들의 삶에 영향을 미치는 근본적인 결정들은 식민 지배자들에 의해 이루어지고, 이는 종종 먼 본국에서 정의된 이익을 추구하기 위한 것이다. 피식민지 주민들과의 문화적 타협을 거부하며, 식민 지배자들은 자신들의 우월성과 통치하도록 정해진 사명을 확신하게 된다.

Colonialism is a relationship between an indigenous (or forcibly imported) majority and a minority of foreign invaders. The fundamental decisions affecting the lives of the colonised people are made and implemented by the colonial rulers in pursuit of interests that are often defined in a distant metropolis. Rejecting cultural compromises with the colonised population, the colonisers are convinced of their own superiority and their ordained mandate to rule.

줄리안 고에 따르면, “콜로니얼리즘은 한 사회와 그 구성원을 외국의 지배 국가가 직접적으로 정치적으로 통제하는 것을 의미한다… 지배 국가는 정치적 권력을 독점하며, 종속된 사회와 그 구성원을 법적으로 열등한 위치에 머물게 한다.” 그는 또한 “콜로니얼리즘은 무엇보다도 핵심 국가가 다른 영토 그리고 동등한 시민이 아닌 열등한 대상으로 분류된 그 거주민에 대해 주권을 선언하거나 영토를 장악하는 데 기반을 둔다.”고 썼다.

According to Julian Go, “Colonialism refers to the direct political control of a society and its people by a foreign ruling state… The ruling state monopolizes political power and keeps the subordinated society and its people in a legally inferior position.” He also writes, “colonialism depends first and foremost upon the declaration of sovereignty and/or territorial seizure by a core state over another territory and its inhabitants who are classified as inferior subjects rather than equal citizens.”

데이빗 스트랭에 따르면, 디콜로나이제이션은 국제 사회의 법률상의 승인을 받은 주권 국가 지위를 획득하거나 기존의 주권 국가에 완전히 통합됨으로써 이루어진다.

According to David Strang, decolonization is achieved through the attainment of sovereign statehood with de jure recognition by the international community or through full incorporation into an existing sovereign state.

콜로니얼리즘의 유형

Types of colonialism

《타임스》는 한때 세 가지 유형의 식민 제국이 있다고 익살스럽게 표현했다: “영국 식민 제국은 식민지 주민으로 식민지를 만드는 것이고, 독일 식민 제국은 식민지 없이 식민지 주민을 모으는 것이며, 프랑스 식민 제국은 식민지 주민 없이 식민지를 세우는 것이다.” 현대의 콜로니얼리즘 연구에서는 여러 겹치는 범주를 구분하며, 이를 크게 정착형 식민주의, 착취형 식민주의, 대리형 식민주의, 내부형 식민주의의 네 가지 유형으로 분류한다. 일부 사학자들은 국가 형태나 무역 형태 같은 다른 유형의 식민주의도 식별해왔다.

The Times once quipped that there were three types of colonial empire: “The English, which consists in making colonies with colonists; the German, which collects colonists without colonies; the French, which sets up colonies without colonists.” Modern studies of colonialism have often distinguished between various overlapping categories of colonialism, broadly classified into four types: settler colonialism, exploitation colonialism, surrogate colonialism, and internal colonialism. Some historians have identified other forms of colonialism, including national and trade forms.

- 정착형 식민주의는 종종 종교적, 정치적, 경제적 이유로 인해 식민지로의 대규모 이민을 수반한다. 이 형태의 식민주의는 주로 기존의 인구를 대체하려는 목표를 가지고 있으며, 정착지를 설립하기 위해 많은 수의 정착민이 식민지로 이주하는 것을 포함한다. 아르헨티나, 호주, 브라질, 캐나다, 칠레, 중국, 뉴질랜드, 러시아, 남아프리카공화국, 미국, 우루과이, 그리고 (논란의 여지가 있는) 이스라엘은 정착형 식민지화에 의해 현대적인 형태로 만들어지거나 확장된 국가들의 예이다.

- 착취형 식민주의는 식민지 주민의 수가 적고, 본국의 이익을 위해 자연 자원이나 노동을 착취하는 데 중점을 둔다. 이 형태는 식민지 주민들이 정치적, 경제적 행정의 대부분을 구성하는 더 큰 식민지뿐만 아니라 교역소로 구성된다. 아프리카와 아시아의 유럽 식민지화는 주로 착취형 식민주의의 후원으로 이루어졌다.

- 대리형 식민주의는 식민지 강대국의 지원을 받는 정착 프로젝트를 수반하는데, 대부분의 식민지 주민이 지배 권력과 같은 민족 그룹에 속하지 않는 경우를 말한다. 이는 (논란의 여지가 있지만) 팔레스타인 위임통치 지역과 라이베리아 식민지의 케이스로 주장된 바 있다.

- 내부형 식민주의는 국가 내의 지역들 간에 불균등한 구조적 권력을 의미하는 개념이다. 착취의 원천은 국가 내부에서 비롯된다. 이는 통제와 착취가 식민지화한 국가의 사람들로부터 새로 독립한 국가 내의 이민자 집단으로 전이되는 방식에서 입증된다.

- 국가형 식민주의는 정착형 식민주의와 내부형 식민주의의 요소를 모두 포함하는 과정으로, 국가 건설과 식민지화가 상호 연결되어 있으며, 식민지 지배자는 식민지화된 사람들을 자신의 문화적, 정치적 이미지로 재구성하려고 한다. 목표는 이들을 오직 국가가 선호하는 문화의 반영으로만 통합하는 것이다. 대만의 중화민국은 국가형 식민주의 사회의 전형적인 예이다.

- 무역형 식민주의는 상인들의 무역 기회를 지원하기 위해 식민주의적 사업을 수행하는 것을 말한다. 이 형태의 식민주의는 19세기 아시아에서 가장 두드러졌는데, 이 시기에 이전에 고립주의 국가들이 서구 강대국들에 항구를 강제로 개방해야 했다. 아편 전쟁과 일본의 개항이 그 예이다.

- Settler colonialism involves large-scale immigration by settlers to colonies, often motivated by religious, political, or economic reasons. This form of colonialism aims largely to supplant prior existing populations with a settler one, and involves large number of settlers emigrating to colonies for the purpose of establishing settlements. Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, New Zealand, Russia, South Africa, United States, Uruguay, and (controversially) Israel, are examples of nations created or expanded in their contemporary form by settler colonization.

- Exploitation colonialism involves fewer colonists and focuses on the exploitation of natural resources or labour to the benefit of the metropole. This form consists of trading posts as well as larger colonies where colonists would constitute much of the political and economic administration. The European colonization of Africa and Asia was largely conducted under the auspices of exploitation colonialism.

- Surrogate colonialism involves a settlement project supported by a colonial power, in which most of the settlers do not come from the same ethnic group as the ruling power, as it has been (controversially) argued was the case of Mandatory Palestine and the Colony of Liberia.

- Internal colonialism is a notion of uneven structural power between areas of a state. The source of exploitation comes from within the state. This is demonstrated in the way control and exploitation may pass from people from the colonizing country to an immigrant population within a newly independent country.

- National colonialism is a process involving elements of both settler and internal colonialism, in which nation-building and colonization are symbiotically connected, with the colonial regime seeking to remake the colonized peoples into their own cultural and political image. The goal is to integrate them into the state, but only as reflections of the state’s preferred culture. The Republic of China in Taiwan is the archetypal example of a national-colonialist society.

- Trade colonialism involves the undertaking of colonialist ventures in support of trade opportunities for merchants. This form of colonialism was most prominent in 19th-century Asia, where previously isolationist states were forced to open their ports to Western powers. Examples of this include the Opium Wars and the opening of Japan.

사회-문화적 진화

Socio-cultural evolution

식민지 주민들이 인구가 이미 있는 지역에 정착했을 때, 그 지역 사람들의 사회와 문화는 영구적으로 변화했다. 식민지적 관행은 식민지화된 사람들이 전통적인 문화를 포기하도록 직접적이고 간접적으로 강요했다. 예를 들어, 미국 내 유럽 식민지 개척자들은 원주민 아이들이 지배적인 문화에 동화되도록 강요하기 위해 기숙학교 프로그램을 시행했다.

When colonists settled in pre-populated areas, the societies and cultures of the people in those areas permanently changed. Colonial practices directly and indirectly forced the colonized peoples to abandon their traditional cultures. For example, European colonizers in the United States implemented the residential schools program to force native children to assimilate into the hegemonic culture.

문화식민주의는 아메리카 대륙의 메스티조와 같은 문화적, 민족적으로 혼합된 인구뿐만 아니라 프랑스령 알제리 또는 남부 로디지아(1923~65년 사이 짐바브웨의 명칭)에서 볼 수 있는 인종적으로 분리된 인구를 낳았다. 사실, 식민지 강대국들이 지속적이고 일관된 존재감을 확립한 모든 곳에서 하이브리드 커뮤니티가 존재했다.

Cultural colonialism gave rise to culturally and ethnically mixed populations such as the mestizos of the Americas, as well as racially divided populations such as those found in French Algeria or in Southern Rhodesia. In fact, everywhere where colonial powers established a consistent and continued presence, hybrid communities existed.

아시아에서 주목할 만한 예로는 영국계-미얀마인, 영국계-인도인, 버거(스리랑카 내 유라시아계 소수 민족), 유라시아계 싱가포르인, 필리핀계 메스티조, 크리스탕(포르투갈계 유라시아인), 마카오인 등이 있다. 네덜란드령 동인도(후에 인도네시아)에서는 “네덜란드” 정착민의 대다수가 실제로 유라시아인인 인도-유럽인으로, 공식적으로는 식민지에서 유럽 법적 계층에 속했다.

Notable examples in Asia include the Anglo-Burmese, Anglo-Indian, Burgher, Eurasian Singaporean, Filipino mestizo, Kristang, and Macanese peoples. In the Dutch East Indies (later Indonesia) the vast majority of “Dutch” settlers were in fact Eurasians known as Indo-Europeans, formally belonging to the European legal class in the colony.

역사

History

고대

Antiquity

콜로니얼리즘으로 불릴 수 있는 활동은 최소 고대 이집트인들만큼 오래된 역사를 가지고 있다. 페니키아인, 그리스인, 로마인은 고대 식민지를 설립했다. 페니키아는 기원전 1550년부터 기원전 300년까지 지중해 전역에 걸쳐 확산된 진취적인 해상 무역 문화를 가지고 있었다. 이후 페르시아 제국과 다양한 그리스 도시 국가들이 이 전통을 이어 식민지를 설립했다. 로마인들 또한 곧 이 흐름에 합류하여 지중해, 북아프리카, 서아시아 전역에 콜로니아(식민지)들을 설립했다.

Activity that could be called colonialism has a long history, starting at least as early as the ancient Egyptians. Phoenicians, Greeks, and Romans founded colonies in antiquity. Phoenicia had an enterprising maritime trading-culture that spread across the Mediterranean from 1550 BC to 300 BC; later the Persian Empire and various Greek city-states continued on this line of setting up colonies. The Romans would soon follow, setting up coloniae throughout the Mediterranean, in North Africa, and in Western Asia.

중세

Medieval

7세기부터 아랍인들은 중동, 북아프리카, 아시아 및 유럽 일부를 상당 부분 식민지화했다. 9세기부터는 레이프 에릭손 같은 바이킹(노르인)이 영국, 아일랜드, 아이슬란드, 그린란드, 북아메리카, 현재의 러시아와 우크라이나, 프랑스(노르망디), 그리고 시칠리아에 식민지를 설립했다. 9세기에는 지중해 식민지화의 새로운 물결이 시작되었으며, 베네치아인, 제노바인, 아말피인 같은 경쟁자들이 부유했던 비잔틴 제국 또는 동로마 제국의 섬들과 영토로 침투했다. 유럽의 십자군은 레반트 지역의 십자군 국가(Outremer, ‘바다 너머 땅’의 뜻, 1097~1291)와 발트해 연안(12세기 이후)에 식민지 체제를 구축했다. 베네치아는 달마티아를 지배하기 시작했고, 1204년 제4차 십자군의 결말로 비잔틴 제국의 3분의 2를 획득했다고 선언하면서 명목상 최대의 식민지 확장을 이뤘다.

Beginning in the 7th century, Arabs colonized a substantial portion of the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of Asia and Europe. From the 9th century Vikings (Norsemen) such as Leif Erikson established colonies in Britain, Ireland, Iceland, Greenland, North America, present-day Russia and Ukraine, France (Normandy) and Sicily. In the 9th century a new wave of Mediterranean colonisation began, with competitors such as the Venetians, Genovese and Amalfians infiltrating the wealthy previously Byzantine or Eastern Roman islands and lands. European Crusaders set up colonial regimes in Outremer (in the Levant, 1097–1291) and in the Baltic littoral (12th century onwards). Venice began to dominate Dalmatia and reached its greatest nominal colonial extent at the conclusion of the Fourth Crusade in 1204, with the declaration of the acquisition of three octaves of the Byzantine Empire.

근세

Modern

유럽의 근세 시기는 터키의 아나톨리아 식민지화로 시작되었다. 오스만 제국이 1453년에 콘스탄티노플을 정복한 후, 포르투갈의 엔히크 항해왕자(1394-1460)가 발견한 해상 무역로가 무역의 중심이 되었고, 이는 ‘대항해시대’를 촉진하는 데 기여했다.

The European early modern period began with the Turkish colonization of Anatolia. After the Ottoman Empire conquered Constantinople in 1453, the sea routes discovered by Portuguese Prince Henry the Navigator (1394–1460) became central to trade, and helped fuel the Age of Discovery.

카스티야 연합 왕국은 1492년 해상 항해를 통해 아메리카 대륙을 발견하고 교역 거점을 건설하거나 광범위한 땅을 정복했다. 1494년 토르데시야스 조약은 이 “신”대륙의 영토를 스페인 제국과 포르투갈 제국으로 분할했다.

The Crown of Castile encountered the Americas in 1492 through sea travel and built trading posts or conquered large extents of land. The Treaty of Tordesillas divided the areas of these “new” lands between the Spanish Empire and the Portuguese Empire in 1494.

17세기에는 네덜란드 제국과 프랑스 식민 제국이 탄생했으며, 이후 대영제국으로 발전한 잉글랜드의 해외 영토도 등장했다. 또한 덴마크와 스웨덴의 해외 식민지도 이 시기에 설립되었다.

The 17th century saw the birth of the Dutch Empire and French colonial empire, as well as the English overseas possessions, which later became the British Empire. It also saw the establishment of Danish overseas colonies and Swedish overseas colonies.

첫 번째 분리주의 물결은 미국 독립전쟁(1775-1783)으로 시작되었으며, 이는 “제2차” 대영제국(1783-1815)의 부상을 촉진했다. 스페인 제국은 스페인령 아메리카 독립 전쟁(1808-1833)으로 아메리카 대륙에서 대부분 무너졌다. 이후 독일 식민제국과 벨기에 식민제국을 포함하여 여러 새로운 식민지가 설립되었다. 프랑스 혁명 이후, 요한 고트프리트 헤르더(1744-1803), 아우구스트 폰 코체부(1761-1819), 하인리히 폰 클라이스트(1777-1811) 같은 유럽 작가들은 새로운 세계의 억압받는 원주민들과 노예들에 대한 동정을 불러일으키기 위해 다수의 저작물을 발표했으며, 이를 통해 원주민의 이상화가 시작되었다.

A first wave of separatism started with the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), initiating the Rise of the “Second” British Empire (1783–1815). The Spanish Empire largely collapsed in the Americas with the Spanish American wars of independence (1808–1833). Empire-builders established several new colonies after this time, including in the German colonial empire and Belgian colonial empire. Starting with the end of the French Revolution European authors such as Johann Gottfried Herder, August von Kotzebue, and Heinrich von Kleist prolifically published so as to conjure up sympathy for the oppressed native peoples and the slaves of the new world, thereby starting the idealization of native humans.

합스부르크 군주국, 러시아 제국, 오스만 제국은 동시대에 존재했지만, 해양을 넘어 확장하지는 못했다. 대신 이들 제국은 인접한 영토를 정복함으로써 확장했다. 그러나 러시아는 베링 해협을 건너 북아메리카에 일부 식민지를 건설하기도 했다. 1860년대 이후 일본 제국은 유럽의 식민제국을 모델로 삼아 태평양과 아시아 본토에서 영토를 확장했다. 브라질 제국은 남아메리카에서 패권을 두고 싸웠다. 미국은 1898년 미국–스페인 전쟁 이후 해외 영토를 획득했으며, 이를 계기로 “미국제국주의”라는 용어가 생겨났다.

The Habsburg monarchy, the Russian Empire, and the Ottoman Empire existed at the same time but did not expand over oceans. Rather, these empires expanded through the conquest of neighbouring territories. There was, though, some Russian colonization of North America across the Bering Strait. From the 1860s onwards the Empire of Japan modelled itself on European colonial empires and expanded its territories in the Pacific and on the Asian mainland. The Empire of Brazil fought for hegemony in South America. The United States gained overseas territories after the 1898 Spanish–American War, hence, the coining of the term “American imperialism”.

19세기 후반, 많은 유럽 열강이 아프리카 분할에 참여하게 되었다.

In the late 19th century, many European powers became involved in the Scramble for Africa.

20세기

20th century

제1차 세계대전(1914) – 콜로니얼리즘의 정점 – 발발 당시, 전 세계 식민지 인구는 약 5억 6천만 명에 달했으며, 그중 70%는 영국령, 10%는 프랑스령, 9%는 네덜란드령, 4%는 일본령, 2%는 독일령, 2%는 미국령, 3%는 포르투갈령, 1%는 벨기에령, 0.5%는 이탈리아령에 거주하고 있었다. 식민지 열강의 본국 인구는 총 약 3억 7천만 명이었다. 유럽을 제외한 대부분 지역은 공식적인 식민지 통치에서 벗어나기 어려웠으며, 심지어 샴(태국), 중국, 일본, 네팔, 아프가니스탄, 페르시아(이란), 아비시니아(에티오피아)조차도 서구 식민주의적 영향, 즉 조차지, 불평등 조약, 치외법권 등 다양한 수준의 영향을 받았다.

The world’s colonial population at the outbreak of the First World War (1914) – a high point for colonialism – totalled about 560 million people, of whom 70% lived in British possessions, 10% in French possessions, 9% in Dutch possessions, 4% in Japanese possessions, 2% in German possessions, 2% in American possessions, 3% in Portuguese possessions, 1% in Belgian possessions and 0.5% in Italian possessions. The domestic domains of the colonial powers had a total population of about 370 million people. Outside Europe, few areas had remained without coming under formal colonial tutorship – and even Siam, China, Japan, Nepal, Afghanistan, Persia, and Abyssinia had felt varying degrees of Western colonial-style influence – concessions, unequal treaties, extraterritoriality and the like.

식민지가 수익을 냈는지에 대한 질문에 대해, 경제사학자 그로버 클락(1891-1938)은 단호하게 “아니!”라고 주장한다. 그는 모든 경우에서, 특히 식민지를 지원하고 방어하는 데 필요한 군사 체계와 관련된 비용이 그들이 생산한 총 무역량을 초과했다고 보고했다. 대영제국을 제외하면, 식민지는 본국의 잉여 인구가 이주하기에 적합한 목적지를 제공하지 못했다. 식민지가 수익을 냈는지 여부는 관련된 이해관계의 다양성을 인식할 때 복잡한 문제다. 일부 경우에는 식민 열강이 막대한 군사 비용을 지출하면서도 그 혜택은 민간 투자자들이 차지했다. 다른 경우에는 식민 열강이 식민지에 세금을 부과함으로써 행정 비용의 부담을 식민지 자체로 전가하기도 했다.

Asking whether colonies paid, economic historian Grover Clark (1891–1938) argues an emphatic “No!” He reports that in every case the support cost, especially the military system necessary to support and defend colonies, outran the total trade they produced. Apart from the British Empire, they did not provide favoured destinations for the immigration of surplus metropole populations. The question of whether colonies paid is a complicated one when recognizing the multiplicity of interests involved. In some cases colonial powers paid a lot in military costs while private investors pocketed the benefits. In other cases the colonial powers managed to move the burden of administrative costs to the colonies themselves by imposing taxes.

제1차 세계대전(1914-1918) 이후, 승전 연합국들은 독일 식민 제국과 오스만 제국의 많은 영토를 분할하여 국제연맹 위임통치령으로 나누어 가졌다. 이 영토들은 독립을 얼마나 빨리 준비할 수 있는지에 따라 세 등급으로 분류되었다. 1917–1918년에 러시아와 오스트리아 제국은 붕괴했으며, 소련 제국이 시작되었다. 나치 독일은 1940년대 초 동유럽에 단기간의 식민 체제(라이히스코미사리아테, 총독부)를 구축했다.

After World War I (1914–1918), the victorious Allies divided up the German colonial empire and much of the Ottoman Empire between themselves as League of Nations mandates, grouping these territories into three classes according to how quickly it was deemed that they could prepare for independence. The empires of Russia and Austria collapsed in 1917–1918, and the Soviet empire started. Nazi Germany set up short-lived colonial systems (Reichskommissariate, Generalgouvernement) in Eastern Europe in the early 1940s.

제2차 세계대전(1939–1945)의 여파로 탈식민화가 빠르게 진행되었다. 전쟁의 격변으로 주요 식민 열강이 크게 약화되었고, 싱가포르, 인도, 리비아 등 식민지에 대한 통제를 신속히 잃었다. 또한, 유엔은 1945년 헌장에서 탈식민화에 대한 지지를 명확히 했다. 1960년에는 유엔이 「식민지 독립 선언」(1960년 제15차 총회 결의 제1514호)을 발표하며 이러한 입장을 재확인했다. 그러나 프랑스, 스페인, 영국, 미국과 같은 일부 식민 열강은 이 선언에 찬성하지 않고 기권했다.

In the aftermath of World War II (1939–1945), decolonisation progressed rapidly. The tumultuous upheaval of the war significantly weakened the major colonial powers, and they quickly lost control of colonies such as Singapore, India, and Libya. In addition, the United Nations shows support for decolonisation in its 1945 charter. In 1960, the UN issued the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, which affirmed its stance (though notably, colonial empires such as France, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States abstained).

“네오콜로니얼리즘(신식민주의)”라는 단어는 장-폴 사르트르(1905-1980)가 1956년에 만들었으며, 제2차 세계대전 이후 이루어진 탈식민화 이후의 다양한 맥락을 지칭한다. 일반적으로 이는 직접적인 식민지화를 의미하지 않으며, 대신 다른 수단을 통한 식민주의 또는 식민지적 착취를 가리킨다. 구체적으로, 신식민주의는 관세 및 무역에 관한 일반협정(GATT), 중앙아메리카 자유무역협정(CAFTA) 같은 과거 또는 현재의 경제적 관계, 혹은 과거 식민 열강이 촉진한 기업(예: 나이지리아와 브루나이에서의 로열 더치 쉘의 활동)이 제2차 세계대전 이후 탈식민화 운동 이후에도 이전 식민지와 종속국들을 통제하는 데 사용되었다는 이론을 지칭할 수 있다.

The word “neocolonialism” originated from Jean-Paul Sartre in 1956, to refer to a variety of contexts since the decolonisation that took place after World War II. Generally it does not refer to a type of direct colonisation – rather to colonialism or colonial-style exploitation by other means. Specifically, neocolonialism may refer to the theory that former or existing economic relationships, such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the Central American Free Trade Agreement, or the operations of companies (such as Royal Dutch Shell in Nigeria and Brunei) fostered by former colonial powers were or are used to maintain control of former colonies and dependencies after the colonial independence movements of the post–World War II period.

“네오콜로니얼리즘”이라는 용어는 20세기 후반에 이전-식민지들에서 유행하기 시작했다.

The term “neocolonialism” became popular in ex-colonies in the late 20th century.

현대

Contemporary

제국에 인접한 식민지는 역사적으로 제외되어 왔지만, 그것들도 식민지로 볼 수 있다. 일부 사람들은 현대의 식민지 확장을 러시아 제국주의와 중국 제국주의의 경우에서 본다. 학계에서는 시오니즘이 정착형 식민주의로 간주될 수 있는지에 대한 논쟁도 계속되고 있다.

While colonies of contiguous empires have been historically excluded, they can be seen as colonies. Contemporary expansion of colonies is seen by some in case of Russian imperialism and Chinese imperialism. There is also ongoing debate in academia about Zionism as settler colonialism.

영향

Impact

식민주의의 영향은 엄청나고 광범위하다. 즉각적이고 장기적인 다양한 영향에는 전염병의 확산, 불평등한 사회 관계, 부족 해체, 착취, 노예화, 의학의 발전, 새로운 제도의 창설, 폐지론, 개선된 인프라, 기술 발전 등이 포함된다. 식민지적 관행은 또한 정복자의 언어, 문학, 문화 기관의 확산을 촉진하면서 원주민들의 언어와 문화 기관을 위협하거나 소멸시키기도 한다. 식민지화된 사람들의 문화는 또한 제국 국가에 강력한 영향을 미칠 수 있다.

The impacts of colonisation are immense and pervasive. Various effects, both immediate and protracted, include the spread of virulent diseases, unequal social relations, detribalization, exploitation, enslavement, medical advances, the creation of new institutions, abolitionism, improved infrastructure, and technological progress. Colonial practices also spur the spread of conquerors’ languages, literature and cultural institutions, while endangering or obliterating those of Indigenous peoples. The cultures of the colonised peoples can also have a powerful influence on the imperial country.

국경과 관련해서, 영국과 프랑스는 전 세계 국경 전체 길이의 약 40%를 그었다.

With respect to international borders, Britain and France traced close to 40% of the entire length of the world’s international boundaries.

경제, 무역, 상업

Economy, trade and commerce

경제적 확장은 때때로 ‘콜로니얼 서플러스(식민지 흑자)’라고 불리며, 고대 이래로 제국의 확장과 함께 이루어졌다. 그리스의 무역망은 지중해 지역 전역으로 퍼졌고, 로마의 무역은 식민지 지역의 공물을 로마 본국으로 보내는 것을 주요 목표로 삼아 확장되었다다. 스트라본(BC 63~?)에 따르면, 아우구스투스 황제 시기에 로마 이집트의 미오스 호르모스에서 인도로 향하는 로마 선박은 매년 최대 120척에 달했다고 한다. 오스만 제국 하에서 무역로가 발전하면서,

Economic expansion, sometimes described as the colonial surplus, has accompanied imperial expansion since ancient times. Greek trade networks spread throughout the Mediterranean region while Roman trade expanded with the primary goal of directing tribute from the colonised areas towards the Roman metropole. According to Strabo, by the time of emperor Augustus, up to 120 Roman ships would set sail every year from Myos Hormos in Roman Egypt to India. With the development of trade routes under the Ottoman Empire,

구자리 힌두교도, 시리아 무슬림, 유대인, 아르메니아인, 남유럽과 중앙유럽 출신의 기독교인들은 페르시아와 아랍의 말들을 세 제국의 군대에 공급하고, 모카 커피를 델리와 베오그라드로, 페르시아 실크를 인도와 이스탄불로 운반하는 무역로를 운영했다.

Gujari Hindus, Syrian Muslims, Jews, Armenians, Christians from south and central Europe operated trading routes that supplied Persian and Arab horses to the armies of all three empires, Mocha coffee to Delhi and Belgrade, Persian silk to India and Istanbul.

아즈텍 문명은 광범위한 제국으로 발전했으며, 로마 제국처럼 정복한 식민지 지역에서 공물을 거두는 것을 목표로 했다. 아즈텍의 경우, 중요한 공물 중 하나는 종교 의식을 위한 제물의 확보였다.

Aztec civilisation developed into an extensive empire that, much like the Roman Empire, had the goal of exacting tribute from the conquered colonial areas. For the Aztecs, a significant tribute was the acquisition of sacrificial victims for their religious rituals.

반면, 유럽 식민 제국들은 때때로 자국의 식민지와 관련된 무역을 유도하거나 제한하고 방해하여, 활동을 본국을 통해 유입시키고 이에 따라 세금을 부과했다.

On the other hand, European colonial empires sometimes attempted to channel, restrict and impede trade involving their colonies, funneling activity through the metropole and taxing accordingly.

경제 확장의 일반적인 추세에도 불구하고, 이전 유럽 식민지들의 경제 성과는 상당히 다르다. 경제학자 다론 아제몰루(1967-), 사이먼 존슨(1963-), 제임스 A. 로빈슨(1960-)은 「장기적인 성장의 근본적인 원인으로서의 제도」에서 유럽 식민지 개척자들이 다른 식민지들에 미친 경제적 영향을 비교하고, 예를 들어 서아프리카 식민지인 시에라리온, 홍콩, 싱가포르 같은 이전 유럽 식민지들 간의 엄청난 불일치성을 설명할 수 있는 요소들을 연구한다.

Despite the general trend of economic expansion, the economic performance of former European colonies varies significantly. In “Institutions as a Fundamental Cause of Long-run Growth”, economists Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James A. Robinson compare the economic influences of the European colonists on different colonies and study what could explain the huge discrepancies in previous European colonies, for example, between West African colonies like Sierra Leone and Hong Kong and Singapore.

이 논문에 따르면, 경제 제도는 식민지의 성공을 결정하는 중요한 요소로, 이는 재정 성과와 자원의 분배 방식을 결정하기 때문이다. 동시에, 이러한 제도들은 정치 제도, 특히 사실상 및 정당한 정치 권력이 어떻게 분배되는지에 대한 결과이기도 하다. 따라서 다양한 식민지 사례를 설명하기 위해서는 먼저 경제 제도를 형성한 정치 제도에 대해 살펴볼 필요가 있다.

According to the paper, economic institutions are the determinant of the colonial success because they determine their financial performance and order for the distribution of resources. At the same time, these institutions are also consequences of political institutions – especially how de facto and de jure political power is allocated. To explain the different colonial cases, we thus need to look first into the political institutions that shaped the economic institutions.

예를 들어, 흥미로운 관찰 중 하나는 “행운의 반전”이다. – 북미, 호주, 뉴질랜드 같이 1500년 당시 덜 발전한 문명은 인도 무굴 제국이나 아메리카의 잉카 제국처럼 식민지 개척자들이 오기 전 1500년에 번영했던 문명에 속했던 국가보다 훨씬 더 부유해졌다는 점이다. 이 논문에서 제시된 한 가지 설명은 다양한 식민지들의 정치 제도에 초점을 맞추고 있다. 유럽 식민지 개척자들은 그 지역의 자원을 빠르게 추출하여 이익을 얻을 수 있는 경제 제도를 도입할 가능성이 낮았다. 따라서 더 발전된 문명과 인구가 밀집된 지역에서는 유럽 식민지들이 기존의 경제 시스템을 유지하는 것이 더 낫다고 판단했으며, 자원을 추출할 것이 거의 없는 지역에서는 유럽 식민지들이 자신의 이익을 보호하기 위해 새로운 경제 제도를 도입하려 했다. 따라서 정치 제도는 다양한 경제 시스템을 낳았고, 이는 식민지 경제 성과를 결정짓는 요소가 되었다.

For example, one interesting observation is “the Reversal of Fortune” – the less developed civilisations in 1500, like North America, Australia, and New Zealand, are now much richer than those countries who used to be in the prosperous civilisations in 1500 before the colonists came, like the Mughals in India and the Incas in the Americas. One explanation offered by the paper focuses on the political institutions of the various colonies: it was less likely for European colonists to introduce economic institutions where they could benefit quickly from the extraction of resources in the area. Therefore, given a more developed civilisation and denser population, European colonists would rather keep the existing economic systems than introduce an entirely new system; while in places with little to extract, European colonists would rather establish new economic institutions to protect their interests. Political institutions thus gave rise to different types of economic systems, which determined the colonial economic performance.

유럽의 식민지화와 발전은 전 세계에 이미 존재하던 성별에 따른 권력 체계를 변화시켰다. 많은 이전의 식민지 개척자 지역에서 여성들은 생식 또는 농업 통제를 통해 권력, 명성, 또는 권위를 유지했다. 예를 들어, 사하라 사막 이남 아프리카의 특정 지역에서는 여성이 농지를 소유하고 사용권을 가졌다. 남성들이 공동체를 위한 정치적, 사회적 결정을 내리는 동안, 여성들은 마을의 식량 공급이나 개별 가정의 토지를 관리했다. 이는 여성들이 부계 중심의 가부장적인 사회에서도 권력과 자율성을 얻을 수 있도록 했다.

European colonisation and development also changed gendered systems of power already in place around the world. In many pre-colonialist areas, women maintained power, prestige, or authority through reproductive or agricultural control. For example, in certain parts of sub-Saharan Africa women maintained farmland in which they had usage rights. While men would make political and communal decisions for a community, the women would control the village’s food supply or their individual family’s land. This allowed women to achieve power and autonomy, even in patrilineal and patriarchal societies.

유럽 콜로니얼리즘의 부상과 함께 대부분의 경제 시스템에 대한 발전과 산업화의 강력한 추진력이 생겼다. 생산성을 향상시키기 위해 노력할 때, 유럽인들은 주로 남성 노동자들에게 초점을 맞췄다. 외국 원조는 개발 속도를 높이기 위해 대출, 토지, 신용, 도구 등의 형태로 제공되었지만, 오직 남성에게만 배분되었다. 좀 더 유럽적인 방식으로, 여성들은 가정 내에서 더 많은 역할을 맡는 것이 기대되었다. 그 결과, 시간이 지남에 따라 기술적, 경제적, 계급에 따른 성별 격차가 확대되었다. 식민지 내에서, 특정 지역에 존재하는 수탈적인 식민지 기관이 해당 지역의 현대 경제 발전, 제도 및 인프라에 영향을 미친다는 연구 결과가 있다.

Through the rise of European colonialism came a large push for development and industrialisation of most economic systems. When working to improve productivity, Europeans focused mostly on male workers. Foreign aid arrived in the form of loans, land, credit, and tools to speed up development, but were only allocated to men. In a more European fashion, women were expected to serve on a more domestic level. The result was a technologic, economic, and class-based gender gap that widened over time. Within a colony, the presence of extractive colonial institutions in a given area has been found have effects on the modern day economic development, institutions and infrastructure of these areas.

노예와 계약제 하인

Slavery and indentured servitude

유럽 국가들은 유럽 본국을 부유하게 만들기 위해 제국 프로젝트에 착수했다. 비유럽인과 다른 유럽인들에 대한 착취는 제국의 목표를 지원하기 위해 식민지 개척자들에게 받아들여졌다. 이 제국적 목표에서 나온 두 가지 결과는 노예제와 계약 하인의 확장이었다. 17세기에는 영국 식민지 정착민의 거의 삼분의 일이 계약 하인으로 북미에 왔다.

European nations entered their imperial projects with the goal of enriching the European metropoles. Exploitation of non-Europeans and of other Europeans to support imperial goals was acceptable to the colonisers. Two outgrowths of this imperial agenda were the extension of slavery and indentured servitude. In the 17th century, nearly two-thirds of English settlers came to North America as indentured servants.

유럽의 노예상들은 대서양을 통해 많은 수의 아프리카 노예들을 아메리카 대륙으로 데려왔다. 스페인과 포르투갈은 16세기까지 아프리카 식민지인 카보베르데와 상투메 프린시페에서 아프리카 노예들을 데려와 일을 시켰고, 이후 라틴 아메리카로도 노예들을 수출했다. 그 후 영국, 프랑스, 네덜란드가 노예 무역에 참여했다. 유럽의 식민지 시스템은 약 1,100만 명의 아프리카인을 노예로서 카리브 해와 북미, 남미로 데려갔다.

European slave traders brought large numbers of African slaves to the Americas by sail. Spain and Portugal had brought African slaves to work in African colonies such as Cape Verde and São Tomé and Príncipe, and then in Latin America, by the 16th century. The British, French and Dutch joined in the slave trade in subsequent centuries. The European colonial system took approximately 11 million Africans to the Caribbean and to North and South America as slaves.

| European empire 유럽 제국 | Colonial destination 식민지 목적지 | Number of slaves imported between 1450 and 1870 1450년에서 1870년 사이에 수입된 노예의 수 |

| 포르투갈 제국 | 브라질 | 3,646,800 |

| 대영 제국 | 영국 카리브해 | 1,665,000 |

| 프랑스 제국 | 프랑스 카리브해 | 1,600,200 |

| 스페인 제국 | 라틴 아메리카 | 1,552,100 |

| 네덜란드 제국 | 네덜란드 카리브해 | 500,000 |

| 대영 제국 | 영국 북미 | 399,000 |

유럽과 아메리카의 폐지론자들은 아프리카 노예들의 비인도적인 대우에 항의했고, 이는 19세기 말까지 노예 무역(그리고 후에 대부분의 형태의 노예제)을 없애는 결과를 가져왔다. 하나의 (논란이 있는) 학설은 미국 혁명에서 폐지론의 역할을 지적한다: 영국 식민지 본국이 노예제를 불법화하는 방향으로 나아가는 동안, 13개 식민지의 노예를 소유한 엘리트들은 이것이 식민지 이후 독립을 위해 싸우고 노예 기반 경제를 개발하고 유지할 권리를 쟁취하는 이유 중 하나로 여겼다.

Abolitionists in Europe and Americas protested the inhumane treatment of African slaves, which led to the elimination of the slave trade (and later, of most forms of slavery) by the late 19th century. One (disputed) school of thought points to the role of abolitionism in the American Revolution: while the British colonial metropole started to move towards outlawing slavery, slave-owning elites in the Thirteen Colonies saw this as one of the reasons to fight for their post-colonial independence and for the right to develop and continue a largely slave-based economy.

19세기 초부터 시작된 뉴질랜드에서의 영국 식민 활동은 토착 마오리족 사이에서의 노예 약탈과 노예 보유를 종식시키는 데 일조했다. 반면, 1830년대에 남아프리카의 영국 식민 행정부가 공식적으로 노예 제도를 폐지하자 사회에 균열이 생겼고, 이는 보어 공화국에서의 노예제를 영구화하고 아파르트헤이트(남아프리카 공화국 백인정권의 유색인종에 대한 차별 정책) 철학에 영향을 미쳤다.

British colonising activity in New Zealand from the early 19th century played a part in ending slave-taking and slave-keeping among the indigenous Māori. On the other hand, British colonial administration in Southern Africa, when it officially abolished slavery in the 1830s, caused rifts in society which arguably perpetuated slavery in the Boer Republics and fed into the philosophy of apartheid.

노예제 폐지로 인한 노동력 부족은 퀸즐랜드, 영국령 기아나, 피지 등에서 유럽 식민지 개척자들이 새로운 노동력 공급원을 개발하도록 자극했으며, 이로 인해 계약 하인 제도가 다시 도입되었다. 계약 하인은 유럽 식민지 개척자와 계약을 체결했다. 이 계약에 따라 하인은 최소 1년 동안 고용주를 위해 일하며, 고용주는 하인의 식민지로의 이동 경비를 지불하고, 경우에 따라 본국으로의 귀환 비용을 부담하며, 하인에게 임금을 지급하는 데 동의했다. 노동자들은 식민지로 이동하는 데 발생한 여행 경비에 대한 채무를 갚아야 했기 때문에 고용주에게 “계약”으로 묶이게 되었다. 그러나 실제로 계약 하인들은 열악한 노동 조건과 고용주가 부과한 과중한 채무로 인해 착취당했으며, 식민지에 도착한 후에는 고용주와 채무를 협상할 수단이 없었다.

The labour shortages that resulted from abolition inspired European colonisers in Queensland, British Guaiana and Fiji (for example) to develop new sources of labour, re-adopting a system of indentured servitude. Indentured servants consented to a contract with the European colonisers. Under their contract, the servant would work for an employer for a term of at least a year, while the employer agreed to pay for the servant’s voyage to the colony, possibly pay for the return to the country of origin, and pay the employee a wage as well. The employees became “indentured” to the employer because they owed a debt back to the employer for their travel expense to the colony, which they were expected to pay through their wages. In practice, indentured servants were exploited through terrible working conditions and burdensome debts imposed by the employers, with whom the servants had no means of negotiating the debt once they arrived in the colony.

인도와 중국은 식민지 시대 동안 계약 하인을 가장 많이 제공한 지역이었다. 인도 출신 계약 하인들은 아시아, 아프리카, 카리브해 지역의 영국 식민지뿐만 아니라 프랑스와 포르투갈 식민지로도 이동했으며, 중국 계약 하인들은 영국과 네덜란드 식민지로 이동했다. 1830년부터 1930년 사이에 약 30,000,000 명의 계약 노동자가 인도에서 이주했으며, 이 중 24,000,000 명이 인도로 돌아왔다. 중국 또한 유럽 식민지로 더 많은 계약 하인을 보냈으며, 이들 중 비슷한 비율이 중국으로 돌아왔다.

India and China were the largest source of indentured servants during the colonial era. Indentured servants from India travelled to British colonies in Asia, Africa and the Caribbean, and also to French and Portuguese colonies, while Chinese servants travelled to British and Dutch colonies. Between 1830 and 1930, around 30 million indentured servants migrated from India, and 24 million returned to India. China sent more indentured servants to European colonies, and around the same proportion returned to China.

아프리카 분할 이후, 대부분의 식민 정권이 초기에는 노예제와 노예 무역을 억제하는 데 중점을 두었으나 부차적인 목표였다. 식민지 시대가 끝날 무렵, 이 목표는 대부분 성공적으로 달성되었으나, 법률적 금지에도 불구하고 사실상의 종속 상태와 유사한 노예제는 아프리카와 전 세계에서 여전히 지속되고 있다.

Following the Scramble for Africa, an early but secondary focus for most colonial regimes was the suppression of slavery and the slave trade. By the end of the colonial period they were mostly successful in this aim, though slavery persists in Africa and in the world at large with much the same practices of de facto servility despite legislative prohibition.

군혁신

Military innovation

역사적으로 정복 세력은 정복 대상의 군대에 대해 우위를 점하기 위해 혁신을 적용해왔다. 그리스인들은 보병이 방패를 사용하여 전장에서 진격하는 동안 서로를 엄호함으로써 적들에게 자신을 벽처럼 보이게 하는 팔랑크스 시스템을 개발했다. 마케도니아의 필립 2세는 수천 명의 병사를 조직화하여 숙련된 보병 및 기병 연대를 결합한 강력한 전투 부대를 만들었다. 알렉산더 대왕은 정복 과정에서 이러한 군사적 기반을 더욱 활용했다.

Conquering forces have throughout history applied innovation in order to gain an advantage over the armies of the people they aim to conquer. Greeks developed the phalanx system, which enabled their military units to present themselves to their enemies as a wall, with foot soldiers using shields to cover one another during their advance on the battlefield. Under Philip II of Macedon, they were able to organise thousands of soldiers into a formidable battle force, bringing together carefully trained infantry and cavalry regiments. Alexander the Great exploited this military foundation further during his conquests.

스페인 제국은 아즈텍 문명 등에서 사용하던 도끼 날을 부술 수 있는 더 강한 금속, 주로 철로 만든 무기를 사용하여 메소아메리카 전사들에 비해 큰 우위를 점했다. 화약 무기의 사용은 유럽이 아메리카 및 다른 지역에서 정복 대상이 된 민족들에 대한 군사적 우위를 확고히 했다.

The Spanish Empire held a major advantage over Mesoamerican warriors through the use of weapons made of stronger metal, predominantly iron, which was able to shatter the blades of axes used by the Aztec civilisation and others. The use of gunpowder weapons cemented the European military advantage over the peoples they sought to subjugate in the Americas and elsewhere.

제국의 종말

End of empire

일부 식민지 지역, 예를 들어 캐나다와 같은 곳의 주민은 유럽 열강의 일부로서 상대적으로 평화롭고 번영된 삶을 누렸으나, 이는 주로 다수 집단에 국한된 경우가 많았다. 소수 집단인 캐나다 원주민과 프랑스계 캐나다인들은 차별을 경험하며 식민지 정책에 불만을 품었다. 예를 들어, 퀘벡 지역의 프랑스어 사용 주민들은 제1차 세계대전 중 영국을 위해 군 복무를 강제하는 징병제에 반대하는 목소리를 높였으며, 이는 ‘1917년 징병 위기’로 이어졌다. 반면, 다른 유럽 식민지에서는 유럽 정착민과 현지 주민 간의 갈등이 훨씬 더 두드러졌다. 예를 들어, 제국주의 시대 말기에는 인도의 1857년 ‘세포이 반란’ 같은 봉기가 발생하기도 했다.

The populations of some colonial territories, such as Canada, enjoyed relative peace and prosperity as part of a European power, at least among the majority. Minority populations such as First Nations peoples and French-Canadians experienced marginalisation and resented colonial practices. Francophone residents of Quebec, for example, were vocal in opposing conscription into the armed services to fight on behalf of Britain during World War I, resulting in the Conscription crisis of 1917. Other European colonies had much more pronounced conflict between European settlers and the local population. Rebellions broke out in the later decades of the imperial era, such as India’s Sepoy Rebellion of 1857.

유럽 식민지 개척자들이 설정한 영토 경계선은 특히 중앙아프리카와 남아시아에서 기존 원주민들의 경계를 무시한 것이었으며, 이는 이전에 서로 거의 교류가 없던 집단들을 강제로 한데 묶었다. 유럽 식민지 개척자들은 원주민 간의 정치적, 문화적 적대 관계를 고려하지 않고, 자신들의 군사적 통제 하에 평화를 강요했다. 원주민들은 종종 식민지 행정관들의 의도에 따라 강제 이주를 당하곤 했다.

The territorial boundaries imposed by European colonisers, notably in central Africa and South Asia, defied the existing boundaries of native populations that had previously interacted little with one another. European colonisers disregarded native political and cultural animosities, imposing peace upon people under their military control. Native populations were often relocated at the will of the colonial administrators.

1947년 8월, 영국령 인도 분할로 인해 인도가 독립하고 파키스탄이 창설되었다. 이 과정에서 두 나라 간의 이민이 이루어지며 많은 유혈 사태가 발생했다. 인도의 무슬림들과 파키스탄의 힌두교도 및 시크교도들은 각각 자신들이 독립을 위해 염원했던 나라로 이주했다.

The Partition of British India in August 1947 led to the Independence of India and the creation of Pakistan. These events also caused much bloodshed at the time of the migration of immigrants from the two countries. Muslims from India and Hindus and Sikhs from Pakistan migrated to the respective countries they sought independence for.

독립 이후 인구 이동

Post-independence population movement

현대 식민지 시대에 경험했던 이주 양상이 뒤바뀌며, 독립 이후 시대에는 제국 국가로 돌아가는 경로를 따르는 이주가 이루어졌다. 일부 경우에는, 유럽 출신 정착민들이 자신이 태어난 땅이나 조상의 고향으로 돌아가는 움직임이 있었다. 예를 들어, 1962년 알제리 독립 이후 90만 명의 프랑스 식민지 주민들(피에 누아르; 프랑스계 알제리인)이 프랑스로 재정착했으며, 이들 중 상당수는 알제리 혈통이었다. 1974년에서 1979년 사이 아프리카의 옛 식민지가 독립한 후에는 80만 명의 포르투갈계 주민들이 포르투갈로 이주했다. 또한, 네덜란드 서인도 제도에서 네덜란드 군사 통치가 종료된 후, 30만 명의 네덜란드계 정착민들이 네덜란드로 이주했다.

In a reversal of the migration patterns experienced during the modern colonial era, post-independence era migration followed a route back towards the imperial country. In some cases, this was a movement of settlers of European origin returning to the land of their birth, or to an ancestral birthplace. 900,000 French colonists (known as the Pied-Noirs) resettled in France following Algeria’s independence in 1962. A significant number of these migrants were also of Algerian descent. 800,000 people of Portuguese origin migrated to Portugal after the independence of former colonies in Africa between 1974 and 1979; 300,000 settlers of Dutch origin migrated to the Netherlands from the Dutch West Indies after Dutch military control of the colony ended.

제2차 세계대전 후, 네덜란드 동인도에서 약 30만 명의 네덜란드인이 네덜란드로 귀환했으며, 이들 대부분은 인도-유럽인이라고 불리는 유라시아 혈통의 사람들이었다. 이들 중 상당수는 이후 미국, 캐나다, 호주, 뉴질랜드로 이주했다.

After WWII 300,000 Dutchmen from the Dutch East Indies, of which the majority were people of Eurasian descent called Indo Europeans, repatriated to the Netherlands. A significant number later migrated to the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

유럽 식민지 확장 시대를 거치며 전 세계적으로 여행과 이주는 점점 더 빠른 속도로 발전했다. 유럽 국가의 옛 식민지 출신 시민들은 이전 유럽 제국 국가에 정착할 때 이민 권리와 관련하여 일부 면에서 특혜를 받을 수 있다. 예를 들어, 이중 국적 취득에 관대한 정책이 적용되거나, 옛 식민지에 더 큰 이민 할당량이 제공될 수 있다.

Global travel and migration in general developed at an increasingly brisk pace throughout the era of European colonial expansion. Citizens of the former colonies of European countries may have a privileged status in some respects with regard to immigration rights when settling in the former European imperial nation. For example, rights to dual citizenship may be generous, or larger immigrant quotas may be extended to former colonies.

일부 경우에는 이전 유럽 제국 국가들이 옛 식민지와 긴밀한 정치적, 경제적 유대를 계속 유지하고 있다. 영연방은 영국과 그 옛 식민지들, 즉 영연방 회원국들 간의 협력을 촉진하는 조직이다. 프랑스의 옛 식민지들을 위한 유사한 조직으로 프랑코포니가 있으며, 포르투갈의 옛 식민지들을 위해 포르투갈어 사용국 공동체가 비슷한 역할을 하고, 네덜란드의 옛 식민지들을 위한 네덜란드어 연합도 이에 해당한다.

In some cases, the former European imperial nations continue to foster close political and economic ties with former colonies. The Commonwealth of Nations is an organisation that promotes cooperation between and among Britain and its former colonies, the Commonwealth members. A similar organisation exists for former colonies of France, the Francophonie; the Community of Portuguese Language Countries plays a similar role for former Portuguese colonies, and the Dutch Language Union is the equivalent for former colonies of the Netherlands.

옛 식민지에서의 이주는 유럽 국가들에게 문제를 야기하는 경우가 많았으며, 대다수 인구가 옛 식민지에서 이주한 소수 민족에 대해 적대감을 표출하기도 한다. 최근 수십 년간 프랑스에서는 북아프리카 마그레브 지역 출신 이민자들과 프랑스 대다수 인구 사이에서 문화적, 종교적 갈등이 종종 발생했다. 그럼에도 불구하고 이민은 프랑스의 민족 구성을 변화시켰다. 1980년대에 이르러 “내부 파리” 전체 인구의 25%와 수도권 지역의 14%가 외국 출신, 주로 알제리계로 구성되었다.

Migration from former colonies has proven to be problematic for European countries, where the majority population may express hostility to ethnic minorities who have immigrated from former colonies. Cultural and religious conflict have often erupted in France in recent decades, between immigrants from the Maghreb countries of north Africa and the majority population of France. Nonetheless, immigration has changed the ethnic composition of France; by the 1980s, 25% of the total population of “inner Paris” and 14% of the metropolitan region were of foreign origin, mainly Algerian.

전해진 질병

Introduced diseases

탐험가들과 세계 다른 지역 인구 간의 접촉은 종종 새로운 질병을 유입시켰고, 이는 때때로 극도로 치명적인 지역적 전염병을 유발하기도 했다. 예를 들어, 천연두, 홍역, 말라리아, 황열병 등은 콜럼버스 이전의 아메리카에서는 알려지지 않은 질병들이었다.

Encounters between explorers and populations in the rest of the world often introduced new diseases, which sometimes caused local epidemics of extraordinary virulence. For example, smallpox, measles, malaria, yellow fever, and others were unknown in pre-Columbian America.

1518년 히스파니올라 섬에서 원주민 인구의 절반이 천연두로 사망했다. 천연두는 1520년대 멕시코에서도 대규모로 유행하여, 테노치티틀란에서만 15만 명이 사망했으며, 여기에는 황제도 포함되었다. 1530년대 페루에서도 천연두가 퍼져 유럽 정복자들에게 유리한 환경을 제공했다. 17세기에는 홍역으로 인해 멕시코 원주민 200만 명이 추가로 목숨을 잃었다. 1618년에서 1619년 사이, 천연두는 매사추세츠 만 지역의 원주민 90%를 몰살시켰다. 1780년에서 1782년, 그리고 1837년에서 1838년 사이에 발생한 천연두 전염병은 평원 인디언들에게 엄청난 피해와 급격한 인구 감소를 초래했다. 일부 학자들은 신세계 원주민 인구의 최대 95%가 구세계에서 유입된 질병으로 인해 사망했을 가능성이 있다고 믿는다. 수 세기 동안 유럽인들은 이러한 질병에 대한 높은 면역력을 발전시켰지만, 원주민들은 그러한 면역력을 형성할 시간이 없었다.

Half the native population of Hispaniola in 1518 was killed by smallpox. Smallpox also ravaged Mexico in the 1520s, killing 150,000 in Tenochtitlan alone, including the emperor, and Peru in the 1530s, aiding the European conquerors. Measles killed a further two million Mexican natives in the 17th century. In 1618–1619, smallpox wiped out 90% of the Massachusetts Bay Native Americans. Smallpox epidemics in 1780–1782 and 1837–1838 brought devastation and drastic depopulation among the Plains Indians. Some believe that the death of up to 95% of the Native American population of the New World was caused by Old World diseases. Over the centuries, the Europeans had developed high degrees of immunity to these diseases, while the indigenous peoples had no time to build such immunity.

천연두는 호주 원주민 인구를 대거 감소시켰으며, 영국의 식민지 초기 몇 년 동안 약 50%의 원주민이 사망했다. 또한 많은 뉴질랜드 마오리족도 천연두로 목숨을 잃었다. 1848년에서 1849년 사이에는 하와이 원주민 15만 명 중 약 4만 명이 홍역, 백일해, 독감으로 사망한 것으로 추정된다. 유입된 질병, 특히 천연두는 이스터 섬의 원주민 인구를 거의 멸종시켰다. 1875년에는 홍역으로 피지인 4만 명 이상이 사망했으며, 이는 인구의 약 삼분의 일이었다. 19세기 동안 아이누족의 인구도 급격히 감소했는데, 이는 일본 이주민들이 홋카이도에 몰려들며 전염병을 전파한 것과 큰 관련이 있다.

Smallpox decimated the native population of Australia, killing around 50% of indigenous Australians in the early years of British colonisation. It also killed many New Zealand Māori. As late as 1848–49, as many as 40,000 out of 150,000 Hawaiians are estimated to have died of measles, whooping cough and influenza. Introduced diseases, notably smallpox, nearly wiped out the native population of Easter Island. In 1875, measles killed over 40,000 Fijians, approximately one-third of the population. The Ainu population decreased drastically in the 19th century, due in large part to infectious diseases brought by Japanese settlers pouring into Hokkaido.

반대로, 연구자들은 매독의 전조가 콜럼버스의 항해 이후 신세계에서 유럽으로 전파되었을 가능성을 제기했다. 연구 결과는 유럽인들이 열대의 비임질성 세균을 고향으로 가져갔을 수 있으며, 이 세균들이 유럽의 다른 환경에서 더 치명적인 형태로 변이했을 수 있다고 시사했다. 당시 이 질병은 오늘날보다 더 치명적이었으며, 르네상스 시대 유럽에서 매독은 주요한 사망 원인 중 하나였다. 최초의 콜레라 팬데믹은 벵골에서 시작되어 1820년까지 인도 전역으로 퍼졌다. 이 팬데믹 동안 1만 명의 영국 군인과 수많은 인도인들이 사망했다. 1736년에서 1834년 사이, 동인도회사 장교 중 약 10%만이 귀국할 수 있었다. 주로 인도에서 활동했던 발데마어 하프킨(1860-1930)은 1890년대 콜레라와 흑사병에 대한 백신을 개발하고 사용한 인물로, 최초의 미생물학자로 간주된다.

Conversely, researchers have hypothesised that a precursor to syphilis may have been carried from the New World to Europe after Columbus’s voyages. The findings suggested Europeans could have carried the nonvenereal tropical bacteria home, where the organisms may have mutated into a more deadly form in the different conditions of Europe. The disease was more frequently fatal than it is today; syphilis was a major killer in Europe during the Renaissance. The first cholera pandemic began in Bengal, then spread across India by 1820. Ten thousand British troops and countless Indians died during this pandemic. Between 1736 and 1834 only some 10% of East India Company’s officers survived to take the final voyage home. Waldemar Haffkine, who mainly worked in India, who developed and used vaccines against cholera and bubonic plague in the 1890s, is considered the first microbiologist.

콜로니얼리즘이 아프리카인에 미친 인체측정학적 영향에 대한 2021년 외르크 바텐과 로라 마라발의 연구에 따르면, 아프리카인의 평균 신장은 식민지화 초기 1.1센티미터 감소했으며, 이후 식민지 통치 기간 동안 전반적으로 회복하고 증가했다. 저자들은 신장의 감소를 말라리아, 수면병과 같은 질병, 식민지 통치 초기 몇십 년 동안의 강제 노동, 갈등, 토지 강탈, 그리고 소의 전염병인 우역(牛疫) 바이러스에 의한 대규모 소 사망 등 여러 원인으로 설명했다.

According to a 2021 study by Jörg Baten and Laura Maravall on the anthropometric influence of colonialism on Africans, the average height of Africans decreased by 1.1 centimetres upon colonization and later recovered and increased overall during colonial rule. The authors attributed the decrease to diseases, such as malaria and sleeping sickness, forced labor during the early decades of colonial rule, conflicts, land grabbing, and widespread cattle deaths from the rinderpest viral disease.

질병 대응

Countering disease

1803년 초, 스페인 왕실은 천연두 백신을 스페인 식민지로 전달하고, 그곳에서 대규모 백신 접종 프로그램을 수립하는 임무(발미스 원정대)를 조직했다. 1832년까지, 미국 연방 정부는 원주민들을 위한 천연두 백신 접종 프로그램을 시작했다. 몬츠투아르트 엘핀스톤(1779-1859)의 지도 하에, 인도에서는 천연두 백신 접종 프로그램이 전파되기 시작했다. 20세기 초부터는 열대 국가에서 질병을 근절하거나 통제하는 것이 모든 식민지 강국들의 주요한 추진력이 되었다. 아프리카에서의 수면병 전염병은 위험에 처한 수백만 명을 체계적으로 검진하는 이동 팀 덕분에 종식되었다. 20세기에는 의학의 발전 덕분에 여러 나라에서 사망률이 낮아지며 세계 인구는 역사상 가장 큰 증가를 보였다. 세계 인구는 1900년 16억 명에서 오늘날 70억 명 이상으로 증가했다.

As early as 1803, the Spanish Crown organised a mission (the Balmis expedition) to transport the smallpox vaccine to the Spanish colonies, and establish mass vaccination programs there. By 1832, the federal government of the United States established a smallpox vaccination program for Native Americans. Under the direction of Mountstuart Elphinstone a program was launched to propagate smallpox vaccination in India. From the beginning of the 20th century onwards, the elimination or control of disease in tropical countries became a driving force for all colonial powers. The sleeping sickness epidemic in Africa was arrested due to mobile teams systematically screening millions of people at risk. In the 20th century, the world saw the biggest increase in its population in human history due to lessening of the mortality rate in many countries due to medical advances. The world population has grown from 1.6 billion in 1900 to over seven billion today.

식물학

Botany

식민지 식물학은 유럽 식민지 시대에 획득되거나 교역된 새로운 식물들의 연구, 재배, 마케팅 및 명명과 관련된 연구들을 의미한다. 이들 식물의 대표적인 예로는 설탕, 육두구, 담배, 정향, 계피, 기나피, 고추, 사사프라스, 그리고 차가 있다. 이러한 연구는 식민지 야망을 위한 자금을 확보하고, 유럽의 확장을 지원하며, 이러한 사업들의 수익성을 보장하는 데 중요한 역할을 했다. 바스쿠 다 가마(1460년경-1524)와 크리스토퍼 콜럼버스(1451-1506)는 베네치아와 중동 상인들이 지배하는 기존 항로와 독립적으로 몰루카 제도, 인도, 중국에서 향신료, 염료, 비단을 교역하는 새로운 해상로를 개척하려 했다. 헨드릭 반 레헤데(1636-1691), 게오르크 에버하르트 룸피우스(1627-1702), 야코부스 본티우스(1592-1631) 같은 자연주의자들은 유럽인들을 대신하여 동방 식물들에 대한 데이터를 수집했다. 스웨덴은 광범위한 식민지 네트워크를 갖추지 않았지만, 칼 폰 린네(1707-1778)의 식물학 연구를 바탕으로 계피, 차, 쌀을 현지에서 재배하는 방법을 개발하여 비싼 수입품을 대체할 수 있는 방법을 모색했다.

Colonial botany refers to the body of works concerning the study, cultivation, marketing and naming of the new plants that were acquired or traded during the age of European colonialism. Notable examples of these plants included sugar, nutmeg, tobacco, cloves, cinnamon, Peruvian bark, peppers, Sassafras albidum, and tea. This work was a large part of securing financing for colonial ambitions, supporting European expansion and ensuring the profitability of such endeavors. Vasco de Gama and Christopher Columbus were seeking to establish routes to trade spices, dyes and silk from the Moluccas, India and China by sea that would be independent of the established routes controlled by Venetian and Middle Eastern merchants. Naturalists like Hendrik van Rheede, Georg Eberhard Rumphius, and Jacobus Bontius compiled data about eastern plants on behalf of the Europeans. Though Sweden did not possess an extensive colonial network, botanical research based on Carl Linnaeus identified and developed techniques to grow cinnamon, tea and rice locally as an alternative to costly imports.

지리학

Geography

정착민들은 원주민과 제국의 패권 사이에서 연결 고리 역할을 하여, 식민지 세력과 식민지 주민들 사이의 지리적, 이념적, 상업적 격차를 좁혔다. 지리학이 학문으로서 콜로니얼리즘과 어떻게 연관되는지는 논란이 있지만, 지도 제작, 조선, 항해, 광업, 농업 생산성 같은 지리적 도구들은 유럽의 식민지 확장에서 중요한 역할을 했다. 식민지 개척자들의 지구 표면에 대한 인식과 풍부한 실용적인 기술은 그들에게 지식을 제공했고, 이는 다시, 권력을 창출했다.

Settlers acted as the link between indigenous populations and the imperial hegemony, thus bridging the geographical, ideological and commercial gap between the colonisers and colonised. While the extent in which geography as an academic study is implicated in colonialism is contentious, geographical tools such as cartography, shipbuilding, navigation, mining and agricultural productivity were instrumental in European colonial expansion. Colonisers’ awareness of the Earth’s surface and abundance of practical skills provided colonisers with a knowledge that, in turn, created power.

앤 고드레프스카와 닐 스미스는 “제국은 철저히 ‘지리 프로젝트’였다”고 주장한다. 환경 결정론과 같은 역사적 지리학 이론은 세계의 일부 지역이 개발되지 않았다고 주장함으로써 식민주의를 정당화했으며, 이는 왜곡된 진화 개념을 형성하게 했다. 엘렌 처칠 셈플(1863-1932)과 엘스워스 헌팅턴(1876-1947) 같은 지리학자들은 열대 기후에 사는 원주민들과 달리 북부 기후는 활력과 지능을 키운다는 개념을 제시했는데, 이는 환경 결정론과 사회 다윈주의가 결합된 접근 방식이다.

Anne Godlewska and Neil Smith argue that “empire was ‘quintessentially a geographical project’”. Historical geographical theories such as environmental determinism legitimised colonialism by positing the view that some parts of the world were underdeveloped, which created notions of skewed evolution. Geographers such as Ellen Churchill Semple and Ellsworth Huntington put forward the notion that northern climates bred vigour and intelligence as opposed to those indigenous to tropical climates (See The Tropics) viz a viz a combination of environmental determinism and Social Darwinism in their approach.

정치 지리학자들은 또한 식민지 행동이 세계의 물리적 지도화에 의해 강화되었으며, 이를 통해 “그들”과 “우리” 사이를 시각적으로 분리시켰다고 주장한다. 지리학자들은 주로 식민주의와 제국주의의 공간에 초점을 맞추며, 더 구체적으로는 식민주의를 가능하게 하는 공간의 물질적이고 상징적인 전용에 대해 다룬다.

Political geographers also maintain that colonial behaviour was reinforced by the physical mapping of the world, therefore creating a visual separation between “them” and “us”. Geographers are primarily focused on the spaces of colonialism and imperialism; more specifically, the material and symbolic appropriation of space enabling colonialism.

“지도 제작자들은 편리하고 표준화된 형식으로 지리 정보를 제공함으로써 서아프리카를 유럽의 정복, 상업, 식민지로 개방하는 데 일조했다”는 바셋의 말처럼, 지도는 식민주의에서 광범위한 역할을 담당했다. 콜로니얼리즘과 지리학의 관계가 과학적으로 객관적이지 않았기 때문에, 식민지 시대의 지도 제작은 종종 조작되었다. 사회적 규범과 가치관은 지도 제작에 영향을 미쳤다. 식민지 건설 동안 지도 제작자들은 경계를 설정하고 예술을 창조하는 과정에서 수사적 기법을 사용했다. 이러한 수사는 정복한 유럽인의 관점을 선호했으며, 비유럽인이 만든 지도는 즉시 부정확한 것으로 간주되었다. 또한, 유럽의 지도 제작자들은 지도의 중앙에 자신의 민족을 그려 넣는 민족중심주의로 이어진 일련의 규칙을 따라야 했다; 즉, 자신의 민족을 지도 중심에 배치하는 방식이었다. 존 브라이언 할리(1932-1991)는 “지도를 만드는 과정 – 선택, 생략, 단순화, 분류, 계층 구조 생성, ‘상징화’ – 은 모두 생래적으로 수사적인 것이다”라고 말했다.

Maps played an extensive role in colonialism, as Bassett would put it “by providing geographical information in a convenient and standardised format, cartographers helped open West Africa to European conquest, commerce, and colonisation”. Because the relationship between colonialism and geography was not scientifically objective, cartography was often manipulated during the colonial era. Social norms and values had an effect on the constructing of maps. During colonialism map-makers used rhetoric in their formation of boundaries and in their art. The rhetoric favoured the view of the conquering Europeans; this is evident in the fact that any map created by a non-European was instantly regarded as inaccurate. Furthermore, European cartographers were required to follow a set of rules which led to ethnocentrism; portraying one’s own ethnicity in the centre of the map. As J.B. Harley put it, “The steps in making a map – selection, omission, simplification, classification, the creation of hierarchies, and ‘symbolisation’ – are all inherently rhetorical.”

당시 유럽의 지도 제작자들 사이에서 일반적인 관행은 미지의 지역을 “빈 공간”으로 표시하는 것이었다. 이는 식민지 강국들 간에 이러한 지역을 탐험하고 식민지화하려는 경쟁을 촉발시켰다. 제국주의자들은 자신의 국가의 영광을 위해 이러한 공간을 채우는 것을 공격적이고 열정적으로 고대했다. 『인류 지리 사전』은 지도 제작이 ‘발견되지 않은’ 토착적 의미를 지닌 땅을 비우고 “서구식 지명과 국경을 부과함으로써” 이들을 공간적 존재로 만드는 데 사용되었다고 지적한다. 그리하여 “‘처녀지’(가정상 비어 있는 땅, ‘황야’)를 식민지화의 대상으로 준비시키고, (식민지 풍경을 남성의 침투 영역으로 성적화하며,) 외부의 공간을 절대적이고 계량 가능하며 분리 가능한 (소유물로서) 것으로 재구성했다”고 설명한다.

A common practice by the European cartographers of the time was to map unexplored areas as “blank spaces”. This influenced the colonial powers as it sparked competition amongst them to explore and colonise these regions. Imperialists aggressively and passionately looked forward to filling these spaces for the glory of their respective countries. The Dictionary of Human Geography notes that cartography was used to empty ‘undiscovered’ lands of their Indigenous meaning and bring them into spatial existence via the imposition of “Western place-names and borders, [therefore] priming ‘virgin’ (putatively empty land, ‘wilderness’) for colonisation (thus sexualising colonial landscapes as domains of male penetration), reconfiguring alien space as absolute, quantifiable and separable (as property).”

데이비드 리빙스턴(1813-1873)은 “지리학은 시대와 장소에 따라 다른 의미를 지니며, 우리는 지리학과 식민주의의 관계에 대해 경계를 설정하기보다는 열린 마음을 유지해야 한다”고 강조한다. 페인터와 제프리는 지리학이 객관적인 과학이 아니라고 주장하며, 오히려 그것은 물리적 세계에 대한 가정에 기반한 학문이라고 말한다. 공상과학예술에서 나타나는 열대 환경의 외지리적 표현을 비교해 보면, 열대라는 개념이 지리와 무관한 인위적인 사상과 신념의 집합이라는 추측을 뒷받침할 수 있습니다.

David Livingstone stresses “that geography has meant different things at different times and in different places” and that we should keep an open mind in regards to the relationship between geography and colonialism instead of identifying boundaries. Geography as a discipline was not and is not an objective science, Painter and Jeffrey argue, rather it is based on assumptions about the physical world. Comparison of exogeographical representations of ostensibly tropical environments in science fiction art support this conjecture, finding the notion of the tropics to be an artificial collection of ideas and beliefs that are independent of geography.

해양과 우주

Ocean and space

심해와 우주 기술의 현대적 발전으로, 해저와 달의 식민지가 비-지상 식민지 건설의 대상이 되었다.

With contemporary advances in deep sea and outer space technologies, colonization of the seabed and the Moon have become an object of non-terrestrial colonialism.

vs. 제국주의

Versus imperialism

“제국주의”라는 용어는 종종 “식민주의(콜로니얼리즘)”와 혼용되지만, 많은 학자들은 각각 고유한 정의를 갖고 있다고 주장해 왔다. 제국주의와 식민주의는 개인이나 집단에 대한 영향력을 설명하기 위해 사용되어 왔다. 로버트 영(1950-)은 제국주의는 중앙에서 국가 정책으로 운영되며, 이념적 및 재정적 이유로 발전하는 반면, 식민주의는 단순히 정착이나 상업적 의도를 위한 개발이라고 말한다; 그렇지만, 식민주의에는 여전히 침략이 포함된다. 현대의 식민주의 사용은 또한 식민지와 제국 권력 간에 일정한 지리적 분리가 존재함을 암시하는 경향이 있다. 특히 에드워드 사이드(1935-2003)는 제국주의와 식민주의를 구별하며 이렇게 말한다: “제국주의는 ‘먼 영토를 지배하는 지배적인 본국 중심지의 관행, 이론, 태도’를 포함하는 반면, 식민주의는 ‘먼 영토에 정착지를 심는 것’을 의미한다.” 러시아, 중국, 오스만 제국 같은 연육제국(連陸帝國; 인접 영토로만 구성된 제국)들은 전통적으로 식민주의 논의에서 제외되어 왔으나, 이제 그들도 자신들이 지배한 영토로 인구를 보냈다는 사실이 받아들여짐에 따라 이러한 관점이 변화하고 있다.

The term “imperialism” is often conflated with “colonialism”; however, many scholars have argued that each has its own distinct definition. Imperialism and colonialism have been used in order to describe one’s influence upon a person or group of people. Robert Young writes that imperialism operates from the centre as a state policy and is developed for ideological as well as financial reasons, while colonialism is simply the development for settlement or commercial intentions; however, colonialism still includes invasion. Colonialism in modern usage also tends to imply a degree of geographic separation between the colony and the imperial power. Particularly, Edward Said distinguishes between imperialism and colonialism by stating: “imperialism involved ‘the practice, the theory and the attitudes of a dominating metropolitan center ruling a distant territory’, while colonialism refers to the ‘implanting of settlements on a distant territory.’ Contiguous land empires such as the Russian, Chinese or Ottoman have traditionally been excluded from discussions of colonialism, though this is beginning to change, since it is accepted that they also sent populations into the territories they ruled.

제국주의와 식민주의는 모두 그들이 통제하는 땅과 토착 주민에 대한 정치적, 경제적 이점을 규정하지만, 학자들은 때때로 둘 사이의 차이를 설명하는 데 어려움을 겪는다. 제국주의와 식민주의는 모두 다른 존재를 억압하는 데 초점을 맞추고 있지만, 식민주의가 다른 나라를 물리적으로 지배하는 과정이라면, 제국주의는 정치적이고 금전적인 지배를 의미하며, 이는 공식적이거나 비공식적일 수 있다. 식민주의는 지역을 지배하기 시작하는 방법을 결정하는 건축가로 볼 수 있으며, 제국주의는 정복을 위한 이념을 만들고 식민주의와 협력하는 것으로 볼 수 있다. 식민주의는 제국주의 국가가 한 지역을 정복하기 시작하고, 결국 그 지역을 이전 국가가 지배했던 대로 통치할 수 있게 되는 과정을 의미한다. 식민주의의 핵심 의미는 정복된 국가의 귀중한 자산과 공급물을 착취하고, 정복한 국가가 전쟁의 전리품에서 이익을 얻는 것이다. 제국주의의 의미는 제국을 창조하는 것으로, 다른 국가의 땅을 정복하여 자국의 지배력을 증가시키는 것이다. 식민지 건설은 외국에서 온 주민이 특정 지역에서 식민지 자산을 구축하고 보존하는 역할을 한다. 식민지 건설은 지역의 기존 사회 구조, 물리적 구조, 경제를 완전히 변화시킬 수 있으며, 정복한 민족의 특성이 정복당한 원주민들에게 유전되는 것은 드문 일이 아니다. 모국으로부터 멀리 떨어져 있는 식민지는 거의 없다. 따라서 대부분은 결국 별도의 국적을 확립하거나 본국의 완전한 통제 하에 남게 된다.

Imperialism and colonialism both dictate the political and economic advantage over a land and the indigenous populations they control, yet scholars sometimes find it difficult to illustrate the difference between the two. Although imperialism and colonialism focus on the suppression of another, if colonialism refers to the process of a country taking physical control of another, imperialism refers to the political and monetary dominance, either formally or informally. Colonialism is seen to be the architect deciding how to start dominating areas and then imperialism can be seen as creating the idea behind conquest cooperating with colonialism. Colonialism is when the imperial nation begins a conquest over an area and then eventually is able to rule over the areas the previous nation had controlled. Colonialism’s core meaning is the exploitation of the valuable assets and supplies of the nation that was conquered and the conquering nation then gaining the benefits from the spoils of the war. The meaning of imperialism is to create an empire, by conquering the other state’s lands and therefore increasing its own dominance. Colonialism is the builder and preserver of the colonial possessions in an area by a population coming from a foreign region. Colonialism can completely change the existing social structure, physical structure, and economics of an area; it is not unusual that the characteristics of the conquering peoples are inherited by the conquered indigenous populations. Few colonies remain remote from their mother country. Thus, most will eventually establish a separate nationality or remain under complete control of their mother colony.

소련 지도자 블라디미르 레닌(1870-1924)은 “제국주의는 자본주의의 최고 형태”라고 주장하며, “제국주의는 식민주의 이후에 발전했으며, 독점 자본주의에 의해 식민주의와 구별된다”고 말했다.

The Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin suggested that “imperialism was the highest form of capitalism”, claiming that “imperialism developed after colonialism, and was distinguished from colonialism by monopoly capitalism”.

마르크스주의

Marxism

마르크스주의는 콜로니얼리즘을 착취와 사회적 변화를 강요하는 자본주의의 한 형태로 본다. 마르크스는 세계 자본주의 체제 내에서 식민주의가 불균형 발전과 밀접하게 관련되어 있다고 생각했다. 그는 식민주의를 “대규모 파괴, 의존성, 체계적인 착취의 도구로서 왜곡된 경제, 사회심리적 혼란, 대규모 빈곤 및 신식민지 의존성을 생산한다”고 말했다. 식민지는 생산 방식으로 구축된다. 원자재를 찾고 새로운 투자 기회를 찾는 것은 자본 축적을 위한 자본주의 국가들 간의 경쟁의 결과다. 레닌은 식민주의를 제국주의의 근본 원인으로 보았으며, 제국주의는 식민주의를 통해 독점 자본주의로 특징지어진다고 주장했다. 리알 S. 숭가는 이렇게 설명한다: “블라디미르 레닌은 ‘사회주의 혁명과 민족들의 자결권에 관한 논문’에서 민족 자결 원칙을 강력히 옹호하며, 이를 사회주의적 국제주의 프로그램의 필수적인 항목으로 삼았다.” 그는 레닌의 말을 인용하며 “민족의 자결권은 정치적 의미에서 독립할 권리, 억압국과의 자유로운 정치적 분리를 할 권리를 의미한다”고 주장했다. 특히, 정치적 민주주의에 대한 이러한 요구는 분리 독립을 위한 활동과 분리 독립을 위한 국민 투표의 완전한 자유를 의미한다. 한편, 1918년부터 1923년, 그리고 1929년 이후에 RSFSR(러시아 소비에트 연방 사회주의 공화국)과 이후 USSR(소련) 내 비러시아 마르크스주의자들인 술탄 갈리예프(1892-1940)와 바실 샤흐라이프(1888-1920)는 소련 체제를 러시아 제국주의와 식민주의의 새로운 형태로 간주했다.

Marxism views colonialism as a form of capitalism, enforcing exploitation and social change. Marx thought that working within the global capitalist system, colonialism is closely associated with uneven development. It is an “instrument of wholesale destruction, dependency and systematic exploitation producing distorted economies, socio-psychological disorientation, massive poverty and neocolonial dependency”. Colonies are constructed into modes of production. The search for raw materials and the current search for new investment opportunities is a result of inter-capitalist rivalry for capital accumulation. Lenin regarded colonialism as the root cause of imperialism, as imperialism was distinguished by monopoly capitalism via colonialism and as Lyal S. Sunga explains: “Vladimir Lenin advocated forcefully the principle of self-determination of peoples in his “Theses on the Socialist Revolution and the Right of Nations to Self-Determination” as an integral plank in the programme of socialist internationalism” and he quotes Lenin who contended that “The right of nations to self-determination implies exclusively the right to independence in the political sense, the right to free political separation from the oppressor nation. Specifically, this demand for political democracy implies complete freedom to agitate for secession and for a referendum on secession by the seceding nation.” Non-Russian Marxists within the RSFSR and later the USSR, like Sultan Galiev and Vasyl Shakhrai, meanwhile, between 1918 and 1923 and then after 1929, considered the Soviet regime a renewed version of Russian imperialism and colonialism.

가이아나 출신의 역사학자이자 정치 활동가인 월터 로드니(1942-)는 그의 아프리카 내 콜로니얼리즘 비판에서 다음과 같이 말한다:

In his critique of colonialism in Africa, the Guyanese historian and political activist Walter Rodney states:

식민주의의 짧은 기간이 아프리카에 미친 결정적인 영향과 그 부정적인 결과는 주로 아프리카가 권력을 상실했다는 사실에서 비롯된다. 권력은 인간 사회에서 궁극적인 결정 요소로, 어떤 집단 내에서나 집단 간 관계의 기본이 된다. 권력은 자신의 이익을 방어할 수 있는 능력을 의미하며, 필요하다면 어떤 수단을 동원하여 자신의 의지를 강요할 수 있는 능력이다 … 한 사회가 다른 사회에게 권력을 완전히 양도해야만 하는 상황은 그 자체로 저개발의 한 형태다. 식민지 이전의 수세기 동안, 아프리카는 유럽과의 불리한 상업 거래에도 불구하고 사회적, 정치적, 경제적 삶에 대한 일정한 통제를 유지했다. 그러나 이러한 내부 문제에 대한 통제는 식민주의 하에서 사라졌다. 콜로니얼리즘은 무역을 넘어 훨씬 더 진전되었다. 그것은 유럽인들이 아프리카 내의 사회적 기관들을 직접적으로 전유하려는 경향을 의미했다. 아프리카 사람들은 더 이상 토착 문화적 목표와 기준을 설정할 수 없었고, 사회의 젊은 구성원들을 교육하는 데 완전한 권한을 상실했다. 이는 의심할 여지 없이 큰 후퇴였다 … 콜로니얼리즘은 단순히 착취의 시스템이 아니었으며, 그 본질적인 목적은 이른바 ‘본국’으로 이익을 되돌려 보내는 것이었다. 아프리카 관점에서 보면, 이는 아프리카 노동력과 자원으로 생산된 잉여가 지속적으로 아프리카 밖으로 유출되는 것을 의미했다. 그것은 유럽을 발전시키는 것과 동일한 변증법적 과정의 일환이었으며, 아프리카는 개발되지 않은 상태로 남아 있었다. 식민지 아프리카는 국제 자본주의 경제의 일부로, 그 경제에서 잉여가 나와 본국 영역을 먹여 살렸다. 앞서 본 바와 같이, 토지와 노동의 착취는 인간 사회의 발전에 필수적이지만, 이는 착취가 이루어지는 지역 내에서 생산물이 이용 가능하다는 전제 하에 이루어져야 한다.

The decisiveness of the short period of colonialism and its negative consequences for Africa spring mainly from the fact that Africa lost power. Power is the ultimate determinant in human society, being basic to the relations within any group and between groups. It implies the ability to defend one’s interests and if necessary to impose one’s will by any means available … When one society finds itself forced to relinquish power entirely to another society that in itself is a form of underdevelopment … During the centuries of pre-colonial trade, some control over social political and economic life was retained in Africa, in spite of the disadvantageous commerce with Europeans. That little control over internal matters disappeared under colonialism. Colonialism went much further than trade. It meant a tendency towards direct appropriation by Europeans of the social institutions within Africa. Africans ceased to set indigenous cultural goals and standards, and lost full command of training young members of the society. Those were undoubtedly major steps backwards … Colonialism was not merely a system of exploitation, but one whose essential purpose was to repatriate the profits to the so-called ‘mother country’. From an African view-point, that amounted to consistent expatriation of surplus produced by African labour out of African resources. It meant the development of Europe as part of the same dialectical process in which Africa was underdeveloped. Colonial Africa fell within that part of the international capitalist economy from which surplus was drawn to feed the metropolitan sector. As seen earlier, exploitation of land and labour is essential for human social advance, but only on the assumption that the product is made available within the area where the exploitation takes place.

레닌에 따르면, 새로운 제국주의는 자본주의가 자유무역 단계에서 독점 자본주의와 금융 자본 단계로 전환하는 것을 강조했다. 그는 이것이 “세계 분할을 위한 투쟁의 심화와 연결되어 있다”고 말했다. 자유무역이 상품 수출에 의존하는 반면, 독점 자본주의는 은행과 산업에서 얻은 이윤으로 축적된 자본의 수출에 의존했다. 이는 레닌에게 있어 자본주의의 최고 단계였다. 그는 이러한 형태의 자본주의가 자본가들과 착취당한 국가들 사이에서 전쟁을 불러오며, 결국 전자는 패배할 수밖에 없다고 주장했다. 전쟁은 제국주의의 결과라는 것이다. 이러한 사상의 연장선에서, G. N. 우조이그는 “그러나 이 시기의 아프리카 역사를 보다 심도 있게 조사한 결과, 제국주의는 근본적으로 경제적인 동기를 가 경제적인 것이었음이 분명해졌다”고 말했다.

According to Lenin, the new imperialism emphasised the transition of capitalism from free trade to a stage of monopoly capitalism to finance capital. He states it is, “connected with the intensification of the struggle for the partition of the world”. As free trade thrives on exports of commodities, monopoly capitalism thrived on the export of capital amassed by profits from banks and industry. This, to Lenin, was the highest stage of capitalism. He goes on to state that this form of capitalism was doomed for war between the capitalists and the exploited nations with the former inevitably losing. War is stated to be the consequence of imperialism. As a continuation of this thought, G.N. Uzoigwe states, “But it is now clear from more serious investigations of African history in this period that imperialism was essentially economic in its fundamental impulses.”

자유주의와 자본주의

Liberalism and capitalism

고전적 자유주의자들은 일반적으로 식민주의와 제국주의에 대해 추상적인 반대 입장을 취했으며, 애덤 스미스, 프레데릭 바스티아, 리처드 코브덴, 존 브라이트, 헨리 리처드, 허버트 스펜서, H.R. 폭스 본, 에드워드 모렐, 조세핀 버틀러, W.J. 폭스, 윌리엄 이워트 글래드스톤 등이 그 예이다. 그들의 철학은 특히 중상주의를 포함한 식민지 기업이 자유 무역과 자유주의 정책의 원칙에 반한다고 보았다. 애덤 스미스는 《국부론》에서 영국이 모든 식민지에 독립을 부여해야 한다고 주장했으며, 이는 상인들 중 중상주의적 특권을 가진 이들이 손해를 볼 수는 있겠지만, 일반적인 영국 국민들에게는 경제적으로 유익할 것이라고 논증했다.

Classical liberals were generally in abstract opposition to colonialism and imperialism, including Adam Smith, Frédéric Bastiat, Richard Cobden, John Bright, Henry Richard, Herbert Spencer, H.R. Fox Bourne, Edward Morel, Josephine Butler, W.J. Fox and William Ewart Gladstone. Their philosophies found the colonial enterprise, particularly mercantilism, in opposition to the principles of free trade and liberal policies. Adam Smith wrote in The Wealth of Nations that Britain should grant independence to all of its colonies and also argued that it would be economically beneficial for British people in the average, although the merchants having mercantilist privileges would lose out.

인종 및 젠더

Race and gender

식민지 시대에 전 세계적인 식민지화 과정은 “모국”의 사회적, 정치적 신념 체계를 확산하고 종합하는 역할을 했으며, 여기에는 종종 모국 인종의 선천적 인종적 우월성에 대한 믿음이 포함되었다. 콜로니얼리즘은 또한 “모국” 자체 내에서 이러한 동일한 인종적 신념 체계를 강화하는 역할을 했다. 일반적으로 식민지 신념 체계에는 여성보다 남성이 선천적으로 우월하다는 특정 신념도 포함되었다. 이러한 특정 신념은 식민지화되기 전, 식민지 이전 사회에서 그들의 식민지화 이전에 이미 존재했던 경우가 많았다.

During the colonial era, the global process of colonisation served to spread and synthesize the social and political belief systems of the “mother-countries” which often included a belief in a certain natural racial superiority of the race of the mother-country. Colonialism also acted to reinforce these same racial belief systems within the “mother-countries” themselves. Usually also included within the colonial belief systems was a certain belief in the inherent superiority of male over female. This particular belief was often pre-existing amongst the pre-colonial societies, prior to their colonisation.

당시의 인기 있는 정치적 관행들은 유럽 (및/또는 일본) 남성의 권위를 정당화하고, 여성과 식민 모국 출신이 아닌 인종의 열등성을 두개골학, 비교해부학, 골상학 연구를 통해 정당화함으로써 식민 지배를 강화했다. 19세기의 생물학자, 자연학자, 인류학자, 민족학자들은 조르주 퀴비에(1769-1832)가 사라 바트만(1789-1815)을 연구한 사례와 같이 식민지화된 원주민 여성의 연구에 집중했다. 이러한 사례들은 모국 출신 자연학자들의 관찰에 기초하여 인종 간 자연적 우월과 열등의 관계를 수용했다. 이러한 유럽의 연구들은 아프리카 여성의 해부학적 특징, 특히 생식기가 비비, 개코원숭이, 원숭이와 유사하다는 인식을 조장하여, 식민지화된 아프리카인들을 진화적으로 우월하고 따라서 권위를 지닌 유럽 여성의 특징과 구별지었다.

Popular political practices of the time reinforced colonial rule by legitimising European (and/ or Japanese) male authority, and also legitimising female and non-mother-country race inferiority through studies of craniology, comparative anatomy, and phrenology. Biologists, naturalists, anthropologists, and ethnologists of the 19th century were focused on the study of colonised indigenous women, as in the case of Georges Cuvier’s study of Sarah Baartman. Such cases embraced a natural superiority and inferiority relationship between the races based on the observations of naturalists’ from the mother-countries. European studies along these lines gave rise to the perception that African women’s anatomy, and especially genitalia, resembled those of mandrills, baboons, and monkeys, thus differentiating colonised Africans from what were viewed as the features of the evolutionarily superior, and thus rightfully authoritarian, European woman.

현재는 사이비 과학으로 여겨질 인종에 대한 연구와 더불어, 당시에는 모국 인종의 우월성을 내재적으로 믿게 하는 경향이 있었으며, 젠더 역할에 관한 새로운 이른바 “과학 기반” 이데올로기가 등장했다. 이는 식민 시대의 내재적 우월성에 대한 일반적인 신념 체계의 부속물로 여겨졌다. 모든 문화권에서 여성의 열등성은 두개골학에 의해 뒷받침된다고 주장되는 아이디어로, 과학자들은 평균적으로 여성의 뇌 크기가 남성보다 약간 더 작다는 점을 근거로 여성은 덜 발달되고 진화적으로 남성보다 뒤처져 있다고 추론했다. 이러한 상대적인 두개골 크기 차이 발견은 나중에 인간 남성의 신체 크기가 일반적으로 여성보다 더 크다는 전반적인 특징에 기인하는 것으로 설명되었다.

In addition to what would now be viewed as pseudo-scientific studies of race, which tended to reinforce a belief in an inherent mother-country racial superiority, a new supposedly “science-based” ideology concerning gender roles also then emerged as an adjunct to the general body of beliefs of inherent superiority of the colonial era. Female inferiority across all cultures was emerging as an idea supposedly supported by craniology that led scientists to argue that the typical brain size of the female human was, on the average, slightly smaller than that of the male, thus inferring that therefore female humans must be less developed and less evolutionarily advanced than males. This finding of relative cranial size difference was later attributed to the general typical size difference of the human male body versus that of the typical human female body.

과거 유럽 식민지에서는 당시 지배적이었던 친식민 과학 이데올로기의 명분으로 인해 비유럽인과 여성들이 식민 지배 세력에 의해 때때로 침해적인 연구를 겪기도 했다.

Within the former European colonies, non-Europeans and women sometimes faced invasive studies by the colonial powers in the interest of the then prevailing pro-colonial scientific ideology of the day.

타자화

Othering

타자화는 반복되는 특성으로 인해 다르거나 비정상으로 분류된 개인이나 집단을 별개의 존재로 만드는 과정이다. 타자화는 차별을 하는 이들이 사회적 규범에 부합하지 않는 사람들을 구별하고, 분류하며, 낙인찍기 위해 만들어낸 개념이다. 최근 수십 년 동안 여러 학자들은 “타자”라는 개념을 사회 이론에서 인식론적 개념으로 발전시켰다. 예를 들어, 탈식민주의 학자들은 식민 지배 세력은 “타자”를 지배하고, 문명화하며, 토지를 식민화하여 자원을 착취하기 위해 존재하는 존재로 설명했다고 보았다.

Othering is the process of creating a separate entity to persons or groups who are labelled as different or non-normal due to the repetition of characteristics. Othering is the creation of those who discriminate, to distinguish, label, categorise those who do not fit in the societal norm. Several scholars in recent decades developed the notion of the “other” as an epistemological concept in social theory. For example, postcolonial scholars, believed that colonising powers explained an “other” who were there to dominate, civilise, and extract resources through colonisation of land.

정치 지리학자들은 식민지/제국주의 세력이 그들의 토지 착취를 정당화하기 위해 지배하려는 지역을 어떻게 “타자화”했는지를 설명한다. 식민주의의 부상 동안과 이후 서구 열강은 동양을 자신들의 사회적 규범과 다르고 분리된 “타자”로 인식했다. 이러한 관점과 문화의 분리는 동양과 서양 문화를 분열시켜 지배와 종속의 역학 관계를 형성했으며, 양측 모두 서로를 “타자”로 간주하게 만들었다.

Political geographers explain how colonial/imperial powers “othered” places they wanted to dominate to legalise their exploitation of the land. During and after the rise of colonialism the Western powers perceived the East as the “other”, being different and separate from their societal norm. This viewpoint and separation of culture had divided the Eastern and Western culture creating a dominant/subordinate dynamic, both being the “other” towards themselves.

포스트-콜로니얼리즘

Post-colonialism

탈식민주의(또는 탈식민 이론)는 식민 통치의 유산을 다루는 철학과 문학의 일련의 이론을 지칭할 수 있다. 이러한 관점에서 탈식민 문학은 과거 식민 제국에 의해 지배받던 민족들의 정치적·문화적 독립에 관심을 두는 포스트모더니즘 문학의 한 갈래로 볼 수 있다.

Post-colonialism (or post-colonial theory) can refer to a set of theories in philosophy and literature that grapple with the legacy of colonial rule. In this sense, one can regard post-colonial literature as a branch of postmodern literature concerned with the political and cultural independence of peoples formerly subjugated in colonial empires.