Pictorialism

픽토리얼리즘(일명 회화주의)은 19세기 후반과 20세기 초에 사진을 지배했던 국제적인 스타일이자 미학적 운동이다. 이 용어에 대한 표준 정의는 없지만, 일반적으로 사진가가 단순히 사진을 기록하는 대신 이미지를 창조하기 위한 수단으로 간단한(솔직한) 사진을 어느 정도 조작한 스타일을 의미한다. 전형적으로, 회화적인 사진은 (정도에 따라 다르지만) 선명한 초점이 부족한 듯 보이며, 흑백이 아닌 하나 이상의 색상(웜-브라운부터 딥-블루까지)으로 인화되고, 표면에 눈에 띄는 붓 자국이나 기타 조작이 가해질 수 있다. 픽토리얼리스트에게 사진은 회화, 드로잉 또는 판화처럼 보는 사람의 상상 영역에 감정적인 의도를 투영하는 방법이었다.

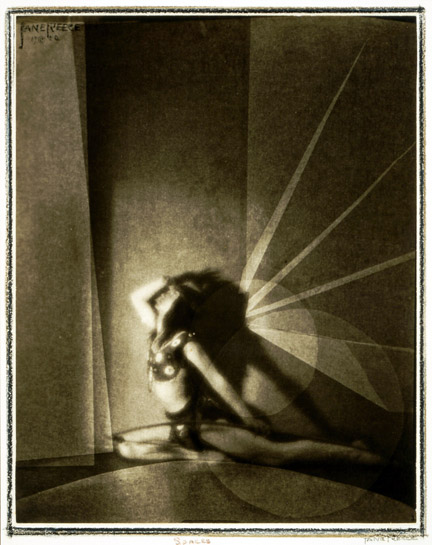

Pictorialism is an international style and aesthetic movement that dominated photography during the later 19th and early 20th centuries. There is no standard definition of the term, but in general it refers to a style in which the photographer has somehow manipulated what would otherwise be a straightforward photograph as a means of creating an image rather than simply recording it. Typically, a pictorial photograph appears to lack a sharp focus (some more so than others), is printed in one or more colors other than black-and-white (ranging from warm brown to deep blue) and may have visible brush strokes or other manipulation of the surface. For the pictorialist, a photograph, like a painting, drawing or engraving, was a way of projecting an emotional intent into the viewer’s realm of imagination.

운동으로서의 픽토리얼리즘은 약 1885년부터 1915년까지 번성했으며, 일부에서는 1940년대까지도 이를 여전히 장려했다. 이 운동은 사진이 단순히 현실을 기록하는 데 그친다는 주장에 대한 반응으로 시작되었으며, 모든 사진을 진정한 예술 형태로 격상시키기 위한 운동으로 발전했다. 30년이 넘는 기간 동안 화가, 사진가, 예술 평론가들이 상반된 예술 철학을 놓고 논쟁을 벌였으며, 결국 주요 미술관 몇 곳에서 사진을 소장하게 되는 결과로 이어졌다.

Pictorialism as a movement thrived from about 1885 to 1915, although it was still being promoted by some as late as the 1940s. It began in response to claims that a photograph was nothing more than a simple record of reality, and transformed into a movement to advance the status of all photography as a true art form. For more than three decades painters, photographers and art critics debated opposing artistic philosophies, ultimately culminating in the acquisition of photographs by several major art museums.

픽토리얼리즘은 1920년 이후 점차 인기가 줄어들었지만, 제2차 세계대전이 끝날 때까지 완전히 사라지지는 않았다. 이 시기 동안 새로운 사진 양식인 모더니즘이 유행하기 시작했으며, 대중의 관심은 앤설 애덤스의 작품에서 볼 수 있는 것처럼 더 선명하게 초점이 맞춰진 이미지로 옮겨갔다. 몇몇 중요한 20세기 사진가들은 픽토리얼리즘 스타일로 경력을 시작했지만, 1930년대에는 선명하게 초점이 맞춰진 사진으로 전환했다.

Pictorialism gradually declined in popularity after 1920, although it did not fade out of popularity until the end of World War II. During this period the new style of photographic Modernism came into vogue, and the public’s interest shifted to more sharply focused images such as seen in the work of Ansel Adams. Several important 20th-century photographers began their careers in a pictorialist style but transitioned into sharply focused photography by the 1930s.

개관

Overview

암실에서 필름을 현상하고 인화하는 기술적 과정으로서의 사진은 19세기 초 시작되었으며, 전통적인 사진 인화의 선구자들은 1838~1840년 사이에 두드러지게 등장했다. 이 새로운 매체가 자리 잡은 지 얼마 지나지 않아, 사진가, 화가 및 기타 인물들 사이에서 이 매체의 과학적 측면과 예술적 측면 간의 관계에 대한 논쟁이 시작되었다. 일찍이 1853년에 영국 화가 윌리엄 존 뉴턴(1785-1869)은 사진작가가 이미지를 약간 흐릿하게 유지하면 카메라가 예술적인 결과를 만들어낼 수 있다고 제안했다. 다른 사람들은 사진이 화학 실험의 시각적 기록과 동일하다고 굳게 믿었다. 사진 역사가 나오미 로젠블럼(1925-2021)은 “이 매체의 이중적 성격, 즉 예술과 기록을 모두 만들어낼 수 있는 능력은 발견 직후에 입증되었다… 그럼에도 불구하고, 19세기의 대부분은 이 두 방향 중 어느 것이 이 매체의 진정한 기능인지 논의하는 데 할애되었다”고 지적한다.

Photography as a technical process involving the development of film and prints in a darkroom originated in the early 19th century, with the forerunners of traditional photographic prints coming into prominence around 1838 to 1840. Not long after the new medium was established, photographers, painters and others began to argue about the relationship between the scientific and artistic aspects of the medium. As early as 1853, English painter William John Newton proposed that the camera could produce artistic results if the photographer would keep an image slightly out of focus. Others vehemently believed that a photograph was equivalent to the visual record of a chemistry experiment. Photography historian Naomi Rosenblum points out that “the dual character of the medium—its capacity to produce both art and document—[was] demonstrated soon after its discovery … Nevertheless, a good part of the nineteenth century was spent debating which of these directions was the medium’s true function.”

이러한 논쟁은 19세기 말과 20세기 초에 절정에 달했으며, 이는 일반적으로 특정한 사진 스타일로 묘사되는 운동인 ‘픽토리얼리즘’의 탄생으로 이어졌다. 이 스타일은 단순히 사실을 기록하는 것을 넘어, 사진이 시각적 아름다움을 창조할 수 있는 능력을 강조하는 독특하고 개인적인 표현으로 정의된다. 그렇지만, 최근 역사가들은 픽토리얼리즘이 단순한 시각적 스타일 그 이상이라는 점을 인정하고 있다. 이 운동은 당시의 변화하는 사회적·문화적 태도와 직접적인 맥락 속에서 발전했기 때문에 단순히 시각적 유행으로 규정해서는 안 된다. 한 필자는 픽토리얼리즘을 “동시에 하나의 운동, 하나의 철학, 하나의 미학, 그리고 하나의 스타일이었다”고 언급한 바 있다.

These debates reached their peak during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, culminating in the creation of a movement that is usually characterized as a particular style of photography: pictorialism. This style is defined first by a distinctly personal expression that emphasizes photography’s ability to create visual beauty rather than simply record facts. However, recently historians have recognized that pictorialism is more than just a visual style. It evolved in direct context with the changing social and cultural attitudes of the time, and, as such, it should not be characterized simply as a visual trend. One writer has noted that pictorialism was “simultaneously a movement, a philosophy, an aesthetic and a style.”

사진의 일부 역사에서 묘사하는 것과 달리, 픽토리얼리즘은 예술적 감성의 선형적 진화의 결과로 생겨난 것이 아니라, 오히려, “복잡하고 다양하며, 종종 열정적으로 상충하는 전략들의 공세”를 통해 형성된 것이다. 사진가들과 다른 사람들이 사진이 예술이 될 수 있는지에 대해 논쟁하는 동안, 사진의 출현은 많은 전통 예술가들의 역할과 생계에 직접적인 영향을 미쳤다. 사진이 개발되기 전에는, 그려진 미니어처 포트레이트(소형 초상화)가 사람의 모습을 기록하는 가장 일반적인 수단이었다. 수천 명의 화가가 이 예술 형식에 종사했다. 그러나 사진은 미니어처 포트레이트에 대한 필요성과 관심을 빠르게 무력화시켰다. 1830년 런던 왕립아카데미의 연례 전시회에서 300여 점의 미니어처 그림이 전시되었지만, 1870년에는 불과 33점만이 전시되었다. 사진이 예술 형식의 한 유형으로 자리 잡았지만, 사진 자체가 예술적일 수 있는지에 대한 의문은 해결되지 않았다.

Contrary to what some histories of photography portray, pictorialism did not come about as the result of a linear evolution of artistic sensibilities; rather, it was formed through “an intricate, divergent, often passionately conflicting barrage of strategies.” While photographers and others debated whether photography could be art, the advent of photography directly affected the roles and livelihoods of many traditional artists. Prior to the development of photography, a painted miniature portrait was the most common means of recording a person’s likeness. Thousands of painters were engaged in this art form. But photography quickly negated the need for and interest in miniature portraits. One example of this effect was seen at the annual exhibition of the Royal Academy in London; in 1830 more than 300 miniature paintings were exhibited, but by 1870 only 33 were on display. Photography had taken over for one type of art form, but the question of whether photography itself could be artistic had not been resolved.

일부 화가들은 곧 사진을 모델의 포즈, 풍경 장면 또는 자신들의 예술에 포함시킬 요소를 기록하는 도구로 채택했다. 들라크루아, 쿠르베, 마네, 드가, 세잔, 고갱을 포함한 19세기의 많은 위대한 화가들이 직접 사진을 촬영하거나, 다른 사람들이 촬영한 사진을 사용하거나, 사진 이미지를 그들의 작품에 통합한 것으로 알려져 있다. 사진과 예술 간의 관계에 대한 열띤 논쟁이 출판물과 강연장에서 계속되는 동안, 사진 이미지와 회화의 구분은 점점 더 어려워졌다. 사진이 계속 발전함에 따라, 회화와 사진 간의 상호 작용은 더욱 상호적이 되었다. 앨빈 랭던 코번, 에드워드 스타이켄, 거트루드 케시비어, 오스카 구스타브 레일랜더, 사라 쇼트 시어스를 포함한 많은 픽토리얼리즘 사진가들은 원래 화가로 훈련받았거나 사진 기술 외에도 회화를 병행했다.

Some painters soon adopted photography as a tool to help them record a model’s pose, a landscape scene or other elements to include in their art. It is known that many of the great 19th-century painters, including Delacroix, Courbet, Manet, Degas, Cézanne, and Gauguin, took photographs themselves, used photographs by others and incorporated images from photographs into their work. While heated debates about the relationship between photography and art continued in print and in lecture halls, the distinction between a photographic image and a painting became more and more difficult to discern. As photography continued to develop, the interactions between painting and photography became increasingly reciprocal. More than a few pictorial photographers, including Alvin Langdon Coburn, Edward Steichen, Gertrude Käsebier, Oscar Gustave Rejlander, and Sarah Choate Sears, were originally trained as painters or took up painting in addition to their photographic skills.

같은 시기에 전 세계의 문화와 사회는 대륙 간 여행과 상업의 급격한 증가로 영향을 받고 있었다. 한 대륙에서 출판된 책과 잡지가 다른 대륙으로 수출되어 판매되는 일이 점점 더 쉬워졌고, 신뢰할 수 있는 우편 서비스의 발달은 아이디어, 기술, 그리고 특히 사진에서는 실제 인화물의 개별 교환을 촉진했습니다. 이러한 발전으로 인해 픽토리얼리즘은 “거의 모든 다른 사진 장르보다 더욱 국제적인 사진 운동”이 되었습니다. 미국, 영국, 프랑스, 독일, 오스트리아, 일본 및 기타 국가의 사진 동호회들은 정기적으로 서로의 전시에 작품을 대여하고, 기술 정보를 교환하며, 서로의 저널에 에세이와 비평을 게재했다. 영국의 〈링크드 링〉, 미국의 〈포토-시세션〉, 프랑스의 〈포토-클럽 드 파리〉가 주도한 이 운동에서, 처음에는 수백 명, 이후에는 수천 명의 사진가들이 이 다차원적 운동에 대한 공통된 관심을 열정적으로 추구했다. 불과 10여 년이라는 짧은 기간 동안 서유럽, 동유럽, 북미, 아시아, 호주 등지에서 주목할 만한 픽토리얼리즘 사진가들이 등장했다.

It was during this same period that cultures and societies around the world were being affected by a rapid increase in intercontinental travel and commerce. Books and magazines published on one continent could be exported and sold on another with increasing ease, and the development of reliable mail services facilitated individual exchanges of ideas, techniques and, most importantly for photography, actual prints. These developments led to pictorialism being “a more international movement in photography than almost any other photographic genre.” Camera clubs in the U.S., England, France, Germany, Austria, Japan and other countries regularly lent works to each other’s exhibitions, exchanged technical information and published essays and critical commentaries in one another’s journals. Led by The Linked Ring in England, the Photo-Secession in the U.S., and the Photo-Club de Paris in France, first hundreds and then thousands of photographers passionately pursued common interests in this multi-dimensional movement. Within the span of little more than a decade, notable pictorial photographers were found in Western and Eastern Europe, North America, Asia and Australia.

코닥 카메라의 영향력

The impact of Kodak cameras

실용적인 이미지 포착 및 재현 과정이 발명된 후 첫 40년 동안, 사진은 과학, 기계 공학, 예술에 대한 전문 지식과 기술을 가진 소수의 헌신적인 개인들의 영역으로 남아 있었다. 사진을 찍기 위해서는 화학, 광학, 빛, 카메라의 기계 작동 원리, 그리고 이러한 요소들이 장면을 제대로 표현하기 위해 어떻게 결합되는지를 깊이 배워야 했다. 이는 쉽게 배우거나 가볍게 참여할 수 있는 일이 아니었으며, 따라서 상대적으로 소수의 학자, 과학자, 전문 사진작가들에게 제한되었다.

For the first forty years after a practical process of capturing and reproducing images was invented, photography remained the domain of a highly dedicated group of individuals who had expert knowledge of and skills in science, mechanics and art. To make a photograph, a person had to learn a great deal about chemistry, optics, light, the mechanics of cameras and how these factors combine to properly render a scene. It was not something that one learned easily or engaged in lightly, and, as such, it was limited to a relatively small group of academics, scientists and professional photographers.

이 모든 것은 몇 년 만에 변화했다. 1888년, 조지 이스트먼(1854-1932)은 최초의 휴대용 아마추어 카메라인 코닥 카메라를 선보였다. 그것은 “버튼을 누르세요, 나머지는 우리가 처리합니다”라는 슬로건과 함께 시장에 나왔다. 이 카메라는 약 100장의 2.5인치 원형 사진을 촬영할 수 있는 필름 한 롤이 미리 장착되어 있었으며, 쉽게 휴대하거나 손으로 들고 조작할 수 있었다. 필름의 모든 장면을 촬영한 후, 카메라는 뉴욕 로체스터에 있는 코닥 회사로 보내졌고, 그곳에서 필름을 현상하고 인화한 후 새 필름을 장착했다. 이후 카메라와 인화된 사진은 더 많은 사진을 찍을 준비가 된 고객에게 반환되었다.

All of that changed in a few years’ time span. In 1888 George Eastman introduced the first handheld amateur camera, the Kodak camera. It was marketed with the slogan “You press the button, we do the rest.” The camera was pre-loaded with a roll of film that produced about 100 2.5″ round picture exposures, and it could easily be carried and handheld during its operation. After all of the shots on the film were exposed, the whole camera was returned to the Kodak company in Rochester, New York, where the film was developed, prints were made, and new photographic film was placed inside. Then the camera and prints were returned to the customer, who was ready to take more pictures.

이 변화의 영향은 엄청났다. 갑자기 거의 누구나 사진을 찍을 수 있게 되었고, 몇 년 만에 사진은 세계에서 가장 큰 유행 중 하나가 되었다. 사진 수집가 마이클 G. 윌슨(1942-)은 “수천 명의 상업 사진가와 그보다 백 배 많은 아마추어들이 매년 수백만 장의 사진을 찍고 있었다… 전문적인 작업의 질 저하와 스냅샷(사냥에서 유래한 용어로, 조준할 시간을 가지지 않고 빠르게 촬영하는 것을 의미)의 범람은 기술적으로는 좋은 사진이지만 미학적으로는 그저 그런 사진으로 가득 찬 세상을 만들었다”고 말했다.

The impact of this change was enormous. Suddenly almost anyone could take a photograph, and within the span of a few years photography became one of the biggest fads in the world. Photography collector Michael G. Wilson observed “Thousands of commercial photographers and a hundred times as many amateurs were producing millions of photographs annually … The decline in the quality of professional work and the deluge of snapshots (a term borrowed from hunting, meaning to get off a quick shot without taking the time to aim) resulted in a world awash with technically good but aesthetically indifferent photographs.”

이 변화와 동시에 카메라, 필름, 인화에 대한 새로운 수요를 충족시키기 위한 국내외 상업 기업들이 발전했다. 1893년 시카고에서 열린 〈세계 콜롬비아 박람회〉는 2,700만 명 이상의 관람객을 끌어들였으며, 아마추어를 위한 사진이 전례 없는 규모로 마케팅되었다. 세계 각지의 사진을 전시하는 대형 전시관이 여러 개 있었고, 최신 카메라 및 암실 장비를 선보이고 판매하는 제조업체들, 수십 개의 초상화 스튜디오, 심지어 박람회 자체의 현장 기록이 있었다. 갑자기 사진과 사진가들은 가정에서 흔히 접할 수 있는 상품이 되었다.

Concurrent with this change was the development of national and international commercial enterprises to meet the new demand for cameras, films and prints. At the 1893 World Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which attracted more than 27 million people, photography for amateurs was marketed at an unprecedented scale. There were multiple large exhibits displaying photographs from around the world, many camera and darkroom equipment manufacturers showing and selling their latest goods, dozens of portrait studios and even on-the-spot documentation of the Exposition itself. Suddenly photography and photographers were household commodities.

많은 진지한 사진작가들은 경악했다. 그들의 기법, 그리고 일부 그들의 예술이, 새로 참여했고 제멋대로이며 대부분 재능 없는 시민들에 의해 마음대로 사용되고 있었다. 예술과 사진에 관한 논쟁은, 누구나 사진을 찍을 수 있다면 사진은 결코 예술이라고 불릴 수 없다는 주장을 중심으로 더욱 격화되었다. 사진을 예술로 옹호하는 가장 열정적인 사람들 중 일부는 사진을 “이것 또는 저것”의 매체로 보아서는 안 되며 그럴 수도 없다고 지적했다—어떤 사진은 현실의 단순한 기록이지만, 적절한 요소가 결합되면 일부는 확실히 예술 작품이 될 수 있다는 것이다. 《보스턴 이브닝 트랜스크립트》의 미술 평론가 윌리엄 하우 다운스(1854-1941)는 1900년에 이 입장을 요약하며 “예술은 방법과 과정의 문제가 아니라 기질, 취향, 감정의 문제다… 예술가의 손에서, 사진은 예술 작품이 된다… 한 마디로, 사진은 ‒ 예술이든 상업이든 ‒ 사진가가 그것을 무엇으로 만드느냐에 달려 있다.

Many serious photographers were appalled. Their craft, and to some their art, was being co-opted by a newly engaged, uncontrolled and mostly untalented citizenry. The debate about art and photography intensified around the argument that if anyone could take a photograph then photography could not possibly be called art. Some of the most passionate defenders of photography as art pointed out that photography should not and cannot be seen as an “either/or” medium—some photographs are indeed simple records of reality, but with the right elements some are indeed works of art. William Howe Downs, art critic for the Boston Evening Transcript, summed up this position in 1900 by saying “Art is not so much a matter of methods and processes as it is an affair of temperament, of taste and of sentiment … In the hands of the artist, the photograph becomes a work of art … In a word, photography is what the photographer makes it ‒ an art or a trade.”

이 모든 요소들—사진과 예술에 관한 논쟁, 코닥 카메라의 영향력, 그리고 당대의 변화하는 사회적·문화적 가치들—이 결합되어 세기의 전환 시기에 예술과 사진이 독립적으로 그리고 함께 어떻게 나타날지에 대한 진화의 무대를 마련했다. 픽토리얼리즘을 이끈 방향은 사진적 과정들이 확립되자마자 거의 바로 설정되었지만, 19세기 마지막 10년이 되어서야 국제적인 픽토리얼리스트 운동이 결집되었다.

All of these elements—the debates over photography and art, the impacts of Kodak cameras, and the changing social and cultural values of the times—combined to set the stage for an evolution in how art and photography, independently and together, would appear at the turn of the century. The course that drove pictorialism was set almost as soon as photographic processes were established, but it was not until the last decade of the 19th century that an international pictorialist movement came together.

픽토리얼리즘의 정의

Defining pictorialism

1869년 영국의 사진작가 헨리 피치 로빈슨(1830-1901)은 『사진에서의 회화적 효과: 사진가를 위한 구도 및 키아로스쿠로(명암법)에 대한 힌트』라는 책을 출간했다. 이 책은 “픽토리얼”이라는 용어를 특정 스타일 요소인 키아로스쿠로 ‒ 화가와 미술사가들이 사용하는 이탈리아 용어로, 표현적인 분위기를 전달하기 위해 극적인 조명과 음영을 사용하는 것을 말한다 ‒ 의 맥락에서 사진에 처음으로 일반적으로 사용한 사례다. 로빈슨은 이 책에서 자신이 “콤비네이션 프린팅(조합인화”라고 부른 방법을 홍보했는데, 이는 여러 장의 네거티브 또는 인화 사진을 조작하여 개별 이미지의 개별 요소를 새로운 단일 이미지로 결합하는 방식으로 거의 20년 전에 고안한 방식이다. 로빈슨은 이와 같이 사진을 통해 “예술”을 창조했다고 생각했는데, 최종 이미지가 만들어지는 것은 오직 자신의 직접적인 개입을 통해서만 가능했기 때문이다. 로빈슨은 평생 동안 이 용어의 의미를 계속 확장해 나갔다.

In 1869 English photographer Henry Peach Robinson published a book entitled Pictorial Effect in Photography: Being Hints on Composition and Chiaroscuro for Photographers. This is the first common use of the term “pictorial” referring to photography in the context of a certain stylistic element, chiaroscuro ‒ an Italian term used by painters and art historians that refers to the use of dramatic lighting and shading to convey an expressive mood. In his book Robinson promoted what he called “combination printing”, a method he had devised nearly 20 years earlier by combining individual elements from separate images into a new single image by manipulating multiple negatives or prints. Robinson thus considered that he had created “art” through photography, since it was only through his direct intervention that the final image came about. Robinson continued to expand on the meaning of the term throughout his life.

오스카 구스타브 레일랜더, 마르쿠스 아우렐리우스 루트, 존 러스킨을 비롯한 다른 사진가들과 미술 비평가들은 이러한 아이디어에 동조했다. 픽토리얼리즘의 발흥을 이끈 주요한 힘 중 하나는 스트레이트 포토그래피가 순수하게 재현적이라는 믿음이었다 ‒ 즉, 그것은 예술적 해석의 필터 없이 현실을 보여주었다는 것이다. 그것은, 모든 의도와 목적에 있어, 예술적 의도나 가치를 결여한 단순한 시각적 사실의 기록에 불과한 것이었다. 로빈슨과 다른 이들은 “사진의 일반적으로 받아들여진 한계를 극복해야만 동등한 지위가 성취될 수 있다”고 강하게 느꼈다.

Other photographers and art critics, including Oscar Rejlander, Marcus Aurelius Root, and John Ruskin, echoed these ideas. One of the primary forces behind the rise of pictorialism was the belief that straight photography was purely representational ‒ that it showed reality without the filter of artistic interpretation. It was, for all intents and purposes, a simple record of the visual facts, lacking artistic intent or merit. Robinson and others felt strongly that the “usually accepted limitations of photography had to be overcome if an equality of status was to be achieved.”

로베르 드마시(1859-1936)는 후에 「좋은 사진과 예술적인 사진 사이의 차이는 무엇인가?」라는 제목의 글에서 이 개념을 요약했다. 그는 “우리는 회화적 사진(픽토리얼 포토그래피)을 시작하면서, 어쩌면 부지불식간에, 우리 화학 기술의 가장 오래된 공식보다 수백 년 더 오래된 규칙을 엄격히 준수하도록 자신을 묶어 두었다는 것을 깨달아야 한다. 우리는 뒷문을 통해 예술의 신전으로 들어가, 그곳에서 숙련자들 무리 사이에서 우리 자신을 발견했다.”고 썼다.

Robert Demachy later summarized this concept in an article entitled “What Difference Is There Between a Good Photograph and an Artistic Photograph?”. He wrote “We must realize that, on undertaking pictorial photography, we have, unwittingly perhaps, bound ourselves to the strict observance of rules hundreds of years more ancient than the oldest formulae of our chemical craft. We have slipped into the Temple of Art by a back door, and found ourselves amongst the crowd of adepts.”

사진을 예술로 홍보하는 데 있어 도전 과제 중 하나는 예술이 어떻게 보여야 하는지에 대한 다양한 의견이 있었다는 점이다. 1900년 〈제3회 필라델피아 살롱〉에서는 수십 명의 픽토리얼 사진가들이 전시되었는데, 한 비평가는 “대다수의 전시자들이 진정한 의미의 예술에 대해 듣거나 생각해본 적이 있는지”에 대해 의문을 제기했다.

One of the challenges in promoting photography as art was that there were many different opinions about how art should look. After the Third Philadelphia Salon 1900, which showcased dozens of pictorial photographers, one critic wondered “whether the idea of art in anything like the true sense had ever been heard or thought by the great majority of exhibitors.”

일부 사진가들은 회화를 모방함으로써 자신들이 진정한 예술가가 되었다고 보았지만, 적어도 한 회화 학파는 직접적으로 사진가들에게 영감을 주었다. 1880년대 동안, 예술과 사진에 관한 논쟁이 보편화되던 시기에, ‘토널리즘(색조주의)’이라는 회화 스타일이 처음 등장했다. 몇 년 만에 이는 픽토리얼리즘 발전에 중요한 예술적 영향을 미쳤다. 제임스 애벗 맥닐 휘슬러, 조지 이네스, 랄프 앨버트 블레이클록, 아널드 뵈클린과 같은 화가들은 자연의 이미지를 단순히 기록하는 것과는 대조적으로, 자연에 대한 경험의 해석을 예술가의 가장 중요한 의무로 보았다. 이 예술가들에게 그림은 보는 사람에게 감정적인 반응을 전달하는 것이 중요했으며, 이는 그림에서 분위기 있는 요소에 중점을 두고 “모호한 형태와 차분한 색조를 사용하여 애절한 우울감을 [전달함으로써] … 이러한 감정을 이끌어냈다.

While some photographers saw themselves becoming true artists by emulating painting, at least one school of painting directly inspired photographers. During the 1880s, when debates over art and photography were becoming commonplace, a style of painting known as Tonalism first appeared. Within a few years it became a significant artistic influence on the development of pictorialism. Painters such as James McNeill Whistler, George Inness, Ralph Albert Blakelock, and Arnold Böcklin saw the interpretation of the experience of nature, as contrasted with simply recording an image of nature, as the artist’s highest duty. To these artists it was essential that their paintings convey an emotional response to the viewer, which was elicited through an emphasis on the atmospheric elements in the picture and by the use of “vague shapes and subdued tonalities … [to convey] a sense of elegiac melancholy.”

이 같은 감수성을 사진에 적용한 알프레드 스티글리츠는 이를 다음과 같이 표현했다: “공기는 우리가 모든 것을 보는 매개체이다. 그러므로, 자연에서와 마찬가지로 사진에서 진정한 가치를 확인하려면 공기기가 있어야 한다. 공기는 모든 선을 부드럽게 하며, 빛과 그늘의 전환을 미세하게 조정한다. 그것은 거리의 감각을 재현하는 데 필수적이다. 멀리 있는 물체의 특징인 흐릿한 윤곽선은 공기 때문이다. 이제, 자연에서 공기가 차지하는 역할은, 사진에서 톤이 차지하는 역할이다.”

Applying this same sensibility to photography, Alfred Stieglitz later stated it this way: “Atmosphere is the medium through which we see all things. In order, therefore, to see them in their true value on a photograph, as we do in Nature, atmosphere must be there. Atmosphere softens all lines; it graduates the transition from light to shade; it is essential to the reproduction of the sense of distance. That dimness of outline which is characteristic for distant objects is due to atmosphere. Now, what atmosphere is to Nature, tone is to a picture.”

픽토리얼리즘의 열정적인 동시대 옹호자였던 폴 루이스 앤더슨(1880-1956)은 독자들에게 진정한 예술 사진은 “시사(示唆)와 미스터리”를 전달해야 한다고 조언했는데, 그는 “미스터리란 상상력을 발휘할 기회를 제공하는 것이며, 시사란 직접적이거나 간접적인 방도를 통해 상상력을 자극하는 것을 포함한다”고 설명했다. 픽토리얼리스트들은 과학이 진실된 정보를 요구하는 것에 답할 수는 있지만, 예술은 감각을 자극하려는 인간의 욕구에 부응해야 한다고 주장했다. 이는 각 이미지, 이상적으로는 각 인화물에 개성을 표시하는 방식으로만 이루어질 수 있었다.

Paul Lewis Anderson, a prolific contemporary promoter of pictorialism, advised his readers that true art photography conveyed “suggestion and mystery”, in which “mystery consists in affording an opportunity for the exercise of the imagination, whereas suggestion involves stimulating the imagination by direct or indirect means.” Science, pictorialists contended, might answer a demand for truthful information, but art must respond to the human need for stimulation of the senses. This could only be done by creating a mark of individuality for each image and, ideally, each print.

픽토리얼리스트들의 경우, 진정한 개성은 독창적인 인화물을 통해 표현되었으며, 이는 많은 이들이 예술 사진의 정수로 여겼다. 검프린트나 브로모일 프린트 같은 “이노블링 프로세스”로 불리는 기법들을 통해 이미지의 외형을 조작함으로써, 픽토리얼리스트들은 때때로 드로잉이나 석판 인쇄물로 오인될 만큼 독특한 사진을 만들어낼 수 있었다.

For pictorialists, true individuality was expressed through the creation of a unique print, considered by many to be the epitome of artistic photography. By manipulating the appearance of images through what some called “ennobling processes”, such as gum or bromoil printing, pictorialists were able to create unique photographs that were sometimes mistaken for drawings or lithographs.

픽토리얼리즘 초기의 가장 강력한 옹호자들 중 다수는 새로운 세대의 아마추어 사진가들이었다. 오늘날의 의미와 달리, 당시 논의에서 “아마추어”라는 단어는 다른 함의를 가지고 있었다. 이는 경험이 부족한 초심자를 의미하기보다는, 예술적 탁월함을 추구하고 엄격한 학문적 영향에서 벗어난 자유를 지향하는 사람을 지칭했다. 아마추어는 오랜 역사를 가진 사진 단체들, 예를 들어 영국 왕립사진협회가 제정한 당시의 엄격한 규칙에 얽매이지 않았기 때문에 규칙을 깨뜨릴 수 있는 사람으로 여겨졌다. 영국 저널 《아마추어 포토그래퍼》의 한 기사에서는 “사진은 예술이다 ‒ 아마추어가 능숙함에서 곧 전문가와 대등해지고, 종종 이를 능가하는 유일한 예술일지도 모른다”고 언급했다. 이러한 태도는 전 세계 많은 나라에서 널리 퍼져 있었다. 1893년 〈독일 함부르크 국제 사진전〉에서는 오직 아마추어들의 작품만 출품이 허용되었다. 당시 함부르크 미술관 관장이었던 알프레트 리히트바르크(1852-1914)는 “어떤 매체에서든 유일하게 훌륭한 인물 묘사는 경제적 자유와 실험할 시간이 있는 아마추어 사진가들에 의해서만 이루어지고 있다”고 믿었다.

Many of the strongest voices that championed pictorialism at its beginning were a new generation of amateur photographers. In contrast to its meaning today, the word “amateur” held a different connotation in the discussions of that time. Rather than suggesting an inexperienced novice, the word characterized someone who strived for artistic excellence and a freedom from rigid academic influence. An amateur was seen as someone who could break the rules because he or she was not bound by the then rigid rules set forth by long-established photography organizations like the Royal Photographic Society. An article in the British journal Amateur Photographer stated “photography is an art ‒ perhaps the only one in which the amateur soon equals, and frequently excels, the professional in proficiency.” This attitude prevailed in many countries around the world. At the 1893 Hamburg International Photographic Exhibition in Germany, only the work of amateurs was allowed. Alfred Lichtwark, then director of the Kunsthalle Hamburg believed “the only good portraiture in any medium was being done by amateurs photographers, who had the economic freedom and time to experiment.”

1948년 S.D.조하르는 회화적인 사진(픽토리얼 포토그래프)을 “주로 장면에 대한 미학적 상징적 기록에 작가의 개인적인 의견과 해석이 더해져 관객의 마음에 정서적 반응을 전달할 수 있다. 그것은 독창성, 상상력, 목적의 통일성, repose의 특성을 보여야 하며, 무한한 품격을 지니고 있어야 한다.

In 1948, S.D.Jouhar defined a Pictorial photograph as “mainly an aesthetic symbolic record of a scene plus the artist’s personal comment and interpretation, capable of transmitting an emotional response to the mind of a receptive spectator. It should show originality, imagination, unity of purpose, a quality of repose, and have an infinite quality about it.”

갤러리

Gallery

모더니즘으로의 전환

Transition into Modernism

픽토리얼리즘의 진화는 19세기부터 1940년대까지 느리지만 꾸준하게 이루어졌다. 유럽에서 시작된 픽토리얼리즘은 몇 가지 뚜렷한 단계를 거치며 미국과 전 세계로 퍼져 나갔다. 1890년 이전에는 주로 영국, 독일, 오스트리아, 프랑스에서 옹호자들에 의해 픽토리얼리즘이 등장했다. 1890년대에는 뉴욕과 스티글리츠의 다각적인 노력으로 중심이 이동했다. 1900년까지 픽토리얼리즘은 전 세계로 확산되었으며, 주요 픽토리얼 포토그래피 전시회가 수십 개의 도시에서 개최되었다.

The evolution of pictorialism from the 19th century well into the 1940s was both slow and determined. From its roots in Europe it spread to the U.S. and the rest of the world in several semi-distinct stages. Prior to 1890 pictorialism emerged through advocates who were mainly in England, Germany, Austria and France. During the 1890s the center shifted to New York and Stieglitz’s multi-faceted efforts. By 1900 pictorialism had reached countries around the world, and major exhibitions of pictorial photography were held in dozens of cities.

픽토리얼리즘과 전체 사진 예술에 있어 중요한 순간은 1910년, 뉴욕 버펄로에 있는 올브라이트 갤러리가 스티글리츠의 291 갤러리에서 15점의 사진을 구입하면서 찾아왔다. 이는 사진이 박물관 소장품으로서 가치 있는 예술 형식으로 공식적으로 인정받은 최초의 사례였으며, 많은 사진가들의 사고방식에 확실한 변화를 알리는 신호였다. 오랜 시간 동안 이 순간을 위해 노력했던 스티글리츠는 이미 픽토리얼리즘을 넘어선 새로운 비전을 구상하고 있음을 암시하며 이에 응답했다. 그는 다음과 같이 썼다.

A culminating moment for pictorialism and for photography in general occurred in 1910, when the Albright Gallery in Buffalo bought 15 photographs from Stieglitz’ 291 Gallery. This was the first time photography was officially recognized as an art form worthy of a museum collection, and it signaled a definite shift in many photographers’ thinking. Stieglitz, who had worked so long for this moment, responded by indicating he was already thinking of a new vision beyond pictorialism. He wrote,

이제 픽토리얼 포토그래피의 어리석음과 허식에 일격을 가해야 할 때다… 예술이라는 주장만으로는 충분하지 않다. 사진가가 완벽한 사진을 만들게 하라. 그리고 그가 완벽과 통찰력을 사랑하는 사람이라면, 결과물은 스트레이트하고 아름다운, 진정한 사진이 될 것이다.

It is high time that the stupidity and sham in pictorial photography be struck a solarplexus blow … Claims of art won’t do. Let the photographer make a perfect photograph. And if he happens to be a lover of perfection and a seer, the resulting photograph will be straight and beautiful – a true photograph.

스티글리츠가 현대 회화와 조각에 더 많은 관심을 두기 시작한 직후, 클라렌스 H. 화이트(1871-1925)와 다른 이들이 새로운 세대 사진가들의 리더십을 맡게 되었다. 제1차 세계대전의 가혹한 현실이 전 세계 사람들에게 영향을 미치면서, 대중의 과거 예술에 대한 취향이 변화하기 시작했다. 세계의 선진국들은 점점 더 산업과 성장에 초점을 맞추었고, 예술은 새로운 건물, 비행기, 산업 풍경과 같은 딱딱한 이미지로 이러한 변화를 반영했다.

Soon after Stieglitz began to direct his attention more to modern painting and sculpture, and Clarence H. White and others took over the leadership of a new generation of photographers. As the harsh realities of World War I affected people around the world, the public’s taste for the art of the past began to change. Developed countries of the world focused more and more on industry and growth, and art reflected this change by featuring hard-edged images of new buildings, airplanes and industrial landscapes.

20세기 사진가인 아돌프 파스벤더(1884-1980)는 1960년대까지 픽토리얼 사진을 계속 제작하면서 픽토리얼리즘은 아름다움을 기반으로 하기 때문에 영원하다고 믿었다. 그는 이렇게 썼다. “픽토리얼리즘을 근절하려는 시도는 이상주의, 감정, 그리고 모든 예술과 아름다움의 감각을 파괴해야 하는 것이기 때문에 해결책이 될 수 없다. 픽토리얼리즘은 항상 존재할 것이다.”

Adolf Fassbender, a 20th-century photographer who continued to make pictorial photographs well into the 1960s, believed that pictorialism is eternal because it is based upon beauty first. He wrote “There is no solution in trying to eradicate pictorialism for one would then have to destroy idealism, sentiment and all sense of art and beauty. There will always be pictorialism.”

국가별 픽토리얼리즘

Pictorialism by country

호주

Australia

호주에서 픽토리얼리즘의 주요 촉매 중 하나는 존 카우프만(1864–1942)이었다. 그는 1889년에서 1897년 사이 런던, 취리히, 빈에서 사진 화학 및 인쇄를 공부했다. 1897년 고국으로 돌아온 그는 동료들에게 큰 영향을 미쳤으며, 한 신문에서는 그의 사진을 “예술 작품으로 착각할 수 있다”고 표현하기도 했다. 이후 10년 동안 해롤드 카즈노(1878-1953), 프랭크 헐리(1885-1962), 세실 보스톡(1884-1939), 헨리 말라드(1884-1967), 로즈 시몬즈(1877-1960), 올리브 코튼(1911-2003)과 같은 사진가들이 살롱 및 전시회에서 픽토리얼리즘 작업을 선보였고, 《오스트레일리언 포토그래픽 저널》과 《오스트랄라시안 포토-리뷰》에 그들의 사진을 게재했다.

One of the primary catalysts of pictorialism in Australia was John Kauffmann (1864–1942), who studied photographic chemistry and printing in London, Zurich and Vienna between 1889 and 1897. When he returned to his home country in 1897, he greatly influenced his colleagues by exhibiting what one newspaper called photographs that could be “mistaken for works of art.” Over the next decade a core of photographer artists, including Harold Cazneaux, Frank Hurley, Cecil Bostock, Henri Mallard, Rose Simmonds, and Olive Cotton, exhibited pictorial works at salons and exhibitions across the country and published their photos in the Australian Photographic Journal and the Australasian Photo-Review.

오스트리아

Austria

1891년, 〈빈 아마추어 사진가 클럽〉(클럽 데어 아마퇴어 포토그라픈 인 빈)은 빈에서 최초의 국제 사진 전시회를 개최했다. 이 클럽은 카를 스마, 페데리코 말만, 찰스 스콜릭(1854-1928)에 의해 설립되었으며, 다른 나라의 사진 단체들과의 교류를 촉진하기 위해 만들어졌다. 1893년 알프레드 부슈베크가 클럽의 수장이 된 후, 클럽 이름을 간소화하여 〈비너 카메라 클럽〉으로 변경하고, 1898년까지 발간된 화려한 잡지《비너 포토그라피시 블래터》를 간행하기 시작했다. 이 잡지에는 알프레드 스티글리츠, 로베르 드마시 같은 영향력 있는 외국 사진가들의 기사가 정기적으로 게재되었다.

In 1891 the Club der Amateur Photographen in Wien (Vienna Amateur Photographers’ Club) held the first International Exhibition of Photography in Vienna. The Club, founded by Carl Sma, Federico Mallmann and Charles Scolik, was founded to foster relationships with photographic groups in other countries. After Alfred Buschbeck became head of the club in 1893, it simplified its name to Wiener Camera-Klub (Vienna Camera Club) and began publishing a lavish magazine called Wiener Photographische Blätter that continued until 1898. It regularly featured articles from influential foreign photographers such as Alfred Stieglitz and Robert Demachy.

다른 나라들과 마찬가지로, 넓은 범위의 사진가들이 픽토리얼리즘의 의미가 무엇인지 정의하는 과정에 참여했다. 한스 바첵(1848-1903), 휴고 헨네베르크(1863-1918), 하인리히 쿤(1866-1944)은 프랑스, 독일, 미국과 같은 다른 나라의 단체들과 정보 교류를 증진하기 위해 〈다스 클레블라트〉(세잎클로버)라는 단체를 결성했다. 처음에는 작고 비공식적인 모임이었던 〈다스 클레블라트〉는 국제적인 연결고리를 통해 〈비너 카메라 클럽〉 내에서 영향력을 키웠으며, 이 지역의 다른 도시들에서도 픽토리얼리즘을 장려하는 여러 단체들이 설립되었다. 다른 나라들과 마찬가지로, 제1차 세계대전 이후 픽토리얼리즘에 대한 관심은 줄어들었고, 1920년대에는 대부분의 오스트리아 단체들이 점차 사라지게 되었다.

As in other countries, opposing viewpoints engaged a wider range of photographers in defining what pictorialism meant. Hans Watzek, Hugo Henneberg and Heinrich Kühn formed an organization called Das Kleeblatt (The Trilfolium) expressly to increase the exchange of information with other organizations in other countries, especially, France, Germany and the United States. Initially a small, informal group, Das Kleeblatt increased it influence in the Wiener Camera-Klub through its international connections, and several other organizations promoting pictorialism were created in other cities throughout the region. As in other countries, interest in pictorialism faded after World War I, and eventually most of the Austrian organization slipped into obscurity during the 1920s.

캐나다

Canada

캐나다에서 픽토리얼리즘은 처음에는 시드니 카터(1880–1956)를 중심으로 전개되었다. 그는 캐나다인 중 최초로 ‘포토-시세션’의 회원으로 선출되었으며, 이는 그가 토론토에서 해럴드 모티머-램(1872–1970) 같은 사진가 및 시세셔니스트 퍼시 호진스와 함께 회화주의 사진가 그룹인 〈스튜디오 클럽〉을 결성하도록 영감을 주었다. 1907년, 카터는 몬트리올 미술협회에서 캐나다 최초의 대규모 픽토리얼리즘 전시회를 조직했다. 카터와 동료 사진가 아서 고스(1881-1940)는 〈토론토 카메라 클럽〉 회원들에게 픽토리얼리즘 원칙을 도입하려 했으나, 이러한 노력은 일부 저항에 부딪혔다.

Pictorialism in Canada initially centered on Sidney Carter (1880–1956), the first of his countrymen to be elected to the Photo-Secession. This inspired him to bring together a group of pictorial photographers in Toronto, the Studio Club in Toronto, with Harold Mortimer-Lamb (1872–1970) and fellow Secessionist Percy Hodgins. In 1907 Carter organized Canada’s first major exhibition of pictorial photography at Montreal’s Art Association. Carter and fellow photographer Arthur Goss attempted to introduce pictorialist principles to the members of the Toronto Camera Club, although their efforts were met with some resistance.

영국

England

1853년, 아마추어 사진가 윌리엄 J. 뉴턴은 “나무와 같은 ‘자연물’은 ‘순수 미술의 공인된 원칙’에 따라 촬영해야 한다”는 아이디어를 제안했다. 이후 헨리 피치 로빈슨(1830-1901)과 피터 헨리 에머슨(1856-1936) 같은 초기 사진가들이 사진을 예술로 간주하는 개념을 계속해서 촉진시켰다. 1892년, 로빈슨은 조지 데이비슨(1854-1930), 알프레드 매스켈과 함께 사진을 예술로 이상화하는 데 전념하는 최초의 단체인 〈링크드 링〉을 설립했다. 이들은 프랭크 서트클리프(1853-1941), 프레더릭 H. 에반스(1853-1943), 앨빈 랭던 코번(1882-1966), 프레더릭 홀리어(1838-1933), 제임스 크레이그 아난(1864-1946), 알프레드 호슬리 힌튼(1863-1908) 등 같은 생각을 가진 사진가들을 초청해 회원으로 삼았다. 곧 〈링크드 링〉은 사진을 예술 형식으로 인정받게 하려는 운동의 선두에 서게 되었다.

As early as 1853 amateur photographer William J. Newton proposed the idea that “a ‘natural object’, such as a tree, should be photographed in accordance ‘the acknowledged principles of fine art’”. From there other early photographers, including Henry Peach Robinson and Peter Henry Emerson, continued to promote the concept of photography as art. In 1892 Robinson, along with George Davison and Alfred Maskell, established the first organization devoted specifically to the ideal of photography as art ‒ The Linked Ring. They invited like-minded photographers, including Frank Sutcliffe, Frederick H. Evans, Alvin Langdon Coburn, Frederick Hollyer, James Craig Annan, Alfred Horsley Hinton and others, to join them. Soon The Linked Ring was at the forefront of the movement to have photography regarded as an art form.

〈링크드 링〉이 일부 미국인들을 회원으로 초청한 후, 클럽의 목표와 목적에 대한 논쟁이 일어났다. 1908년 연례 전시회에서 영국 회원보다 미국 회원의 작품이 더 많이 전시되자, 단체를 해체하자는 제안이 제기되었다. 결국 1910년 〈링크드 링〉은 해체되었고, 회원들은 각자의 길을 가게 되었다.

After The Linked Ring invited a select group of Americans as members, debates broke out about the goals and purpose of the club. When more American than British members were shown at their annual exhibit in 1908, a motion was introduced to disband the organization. By 1910 The Linked Ring has dissolved, and its members went their own way.

프랑스

France

프랑스의 회화주의 사진은 콩스탕 퓌요(1859-1933)와 로베르 드마시, 두 인물에 의해 주도되었다. 이들은 〈소시에테 프랑세즈 드 포토그라피〉와는 별개의 단체인 〈포토-클럽 드 파리〉의 가장 유명한 회원들이었다. 이들은 특히 검-바이크로메이트를 포함한 안료 공정을 사용한 것으로 잘 알려져 있다. 1906년, 그들은 이 주제를 다룬 책 『레 프로세데 다르 앙 포토그라피』를 출간했다. 두 사람은 또한 《뷜레탱 뒤 포토-클럽 드 파리》(1891–1902)와 《라 러뷔 드 포토그라피》(1903–1908)에 많은 기사를 썼는데, 후자는 20세기 초반 예술 사진을 다룬 가장 영향력 있는 프랑스 잡지가 되었다. 여성 사진가로는 셀린 라과드(1873-1961)가 이 분야를 선도했으며, 그녀의 작업은 퓌요 및 드마시와 나란히 실렸다.

Pictorialism in France is dominated by two names, Constant Puyo and Robert Demachy. They were the most famous members of the Photo-Club de Paris, a separate organization from the Société française de photographie. They are particularly well known for their use of pigment processes, especially gum bichromate. In 1906, they published a book on the subject, Les Procédés d’art en Photographie. Both of them also wrote many articles for the Bulletin du Photo-Club de Paris (1891–1902) and La Revue de Photographie (1903–1908), a magazine which quickly became the most influential French publication dealing with artistic photography during the early 20th century. Céline Laguarde was the leading woman photographer in the field and her work was published alongside Puyo and Demachy.

독일

Germany

함부르크의 호프마이스터 형제(테오도어와 오스카)는 독일에서 사진을 예술로 옹호한 최초의 인물들 중 하나였다. 아마추어 사진 프로모션 협회(게젤샤프트 츠어 푀어더웅 데어 아마퇴어-포토그라피) 모임에서 하인리히 벡, 게오르그 아인베크(1871-1951), 오토 샤프 등 다른 사진가들도 픽토리얼리즘의 발전을 도왔다. 호프마이스터 형제는 하인리히 쿤과 함께 〈다스 프레지디움(의장단)〉을 결성했으며, 이 단체의 회원들은 함부르크의 쿤스트할레에서 열린 주요 전시회에서 중요한 역할을 했다. 오늘날에는 카를 마리아 우도 레메스가 극장 백스테이지 사진 분야에서 픽토리얼리즘 스타일을 대표하고 있다.

The Hofmeister brothers, Theodor and Oskar, of Hamburg were among the first to advocate for photography as art in their country. At meetings of the Society for the Promotion of Amateur Photography (Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Amateur-Photographie), other photographers, including Heinrich Beck, Georg Einbeck, and Otto Scharf, advanced the cause of pictorialism. The Homeisters, along with Heinrich Kühn, later formed The Presidium (Das Praesidium), whose members were instrumental in major exhibitions at the Kunsthalle in Hamburg. Nowadays Karl Maria Udo Remmes represents the style of pictorialism in the field of theatrical backstage photography.

일본

Japan

1889년, 사진가 오가와 가즈마사(1860-1929), W. K. 버튼(1856-1899), 가지마 세이베이(1866-1924 ) 등 여러 인물들이 일본에서 예술사진(芸術写真, 게이주츠샤신)을 촉진하기 위해 〈일본사진회〉를 결성했다. 이 새로운 스타일은 처음에는 천천히 받아들여졌으나, 1893년 버튼이 〈외국사진예술전람회〉라는 대규모 초청 전시회를 기획하면서 변화가 일어났다. 〈런던 카메라 클럽〉 회원들의 작품을 포함해 총 296점이 전시되었으며, 피터 헨리 에머슨(1856-1936)과 조지 데이비슨(1854-1930)의 중요한 사진들도 포함되었다. 이 전시회는 일본 사진가들에게 지대한 영향을 미쳤으며, “예술 사진에 대한 논의를 전국적으로 활성화”시켰다. 전시회가 끝난 뒤, 버튼과 가지마는 새로운 단체인 〈대일본사진품평회〉를 설립하여 자신들의 예술사진에 대한 견해를 발전시키고자 했다.

In 1889 photographers Ogawa Kazumasa, W. K. Burton, Kajima Seibei and several others formed the Nihon Shashin-kai (Japan Photographic Society) in order to promote geijutsu shashin (art photography) in that country. Acceptance of this new style was slow at first, but in 1893 Burton coordinated a major invitational exhibition known as Gaikoku Shashin-ga Tenrain-kai or the Foreign Photographic Art Exhibition. The 296 works that were shown came from members of the London Camera Club, including important photographs by Peter Henry Emerson and George Davison. The breadth and depth of this exhibition had a tremendous impact on Japanese photographers, and it “galvanized the discourse of art photography throughout the country.” After the exhibition ended Burton and Kajima founded a new organization, the Dai Nihon Shashin Hinpyō-kai (Greater Japan Photography Critique Society) to advance their particular viewpoints on art photography.

1904년, 《샤신겟포(사진월보)》라는 새로운 잡지가 창간되었으며, 여러 해 동안 픽토리얼리즘의 발전과 논쟁의 중심 역할을 했다. 오가와 등 선구자들이 옹호했던 예술사진의 의미와 방향은 이 새로운 잡지에서 사이토 타로와 에가시라 하루키라는 사진가들에 의해 도전받았다. 이들은 아키야마 테츠스케와 가토 세이이치와 함께 〈유쓰즈샤(ゆふつヾ社)〉라는 새로운 단체를 결성했다. 이 단체는 예술사진의 “내면의 진실”이라고 부르는 자신들만의 개념을 홍보했다. 이후 10년 동안 많은 사진가들이 이 두 단체 중 하나에 속하며 활동했다.

In 1904 a new magazine called Shashin Geppo (Monthly Photo Journal) was started, and for many years it was the centerpiece for the advancement of and debates about pictorialism. The meaning and direction of art photography as championed by Ogawa and others was challenged in the new journal by photographers Tarō Saitō and Haruki Egashira, who, along with Tetsusuke Akiyama and Seiichi Katō, formed a new group known as Yūtsuzu-sha. This new group promoted their own concepts of what they called “the inner truth” of art photography. For the next decade many photographers aligned themselves with one of these two organizations.

1920년대에는 픽토리얼리즘에서 모더니즘으로의 전환을 연결하는 새로운 단체들이 결성되었다. 그 중 가장 두드러진 것은 후쿠하라 신조(1883-1948)와 그의 형제 후쿠하라 로소(1892-1946)가 결성한 〈샤신게이주츠샤(사진예술사)〉였다. 이들은 이미지의 과도한 조작을 거부하고, 실버 젤라틴 인쇄를 사용하여 부드러운 초점을 맞춘 이미지를 통해 ‘히카리 토 소노 카이쵸(光とその調和, 빛과 그 조화)’라는 개념을 홍보했다.

In the 1920s new organizations were formed that bridged the transition between pictorialism and modernism. Most prominently among these was the Shashin Geijustu-sha (Photographic Art Society) formed by Shinzō Fukuhara and his brother Rosō Fukuhara. They promoted the concept of hikari to sono kaichō (light with its harmony) that rejected an overt manipulation of an image in favor of soft-focused images using silver gelatin printing.

한국

Korea

네덜란드

Netherlands

네덜란드의 첫 번째 픽토리얼리즘 사진가들인 브람 로만, 크리스 스휘버, 칼 에밀 뫼글레(1857-1934)는 1890년경에 활동을 시작했다. 이들은 처음에 자연주의적인 주제를 중심으로 작업했으며, 플래티넘 인쇄를 선호했다. 처음에는 〈링크드 링〉이나 〈포토-시세션〉 같은 네덜란드의 동등한 단체가 없었지만, 여러 작은 단체들이 협력하여 1904년에 〈제1회 국제 예술 사진 전시회〉를 개최했다. 3년 후, 아드리안 보어, 어니스트 뢰브, 요한 하이센 등이 네덜란드 예술사진클럽을 창립하였고, 이 클럽은 현재 라이덴 대학교에 소장된 중요한 픽토리얼리즘 컬렉션을 모았다. 네덜란드의 두 번째 세대 픽토리얼리즘 사진가들로는 헨리 베르센브루헤(1873-1959), 베르나르트 에일러스(1878-1951), 베렌드 즈베이르스(1872-1946) 등이 있었다.

The first generation of Dutch pictorialists, including Bram Loman, Chris Schuver, and Carl Emile Mögle, began working around 1890. They initially focused on naturalistic themes and favored platinum printing. Although initially there was no Dutch equivalent of The Linked Ring or Photo-Secession, several smaller organizations collaborated to produce the First International Salon for Art Photography in 1904. Three years later Adriann Boer, Ernest Loeb, Johan Huijsen, and others founded the Dutch Club for Art Photography (Nederlandsche Club voor Foto-Kunst), which amassed an important collection of pictorial photography now housed at Leiden University. A second generation of Dutch pictorialists included Henri Berssenbrugge, Bernard Eilers and Berend Zweers.

러시아

Russia

픽토리얼리즘은 유럽 잡지를 통해 먼저 러시아로 전파되었으며, 러시아의 사진 선구자 예브게니 비시냐코프와 폴란드의 얀 불하크(1876-1950)에 의해 옹호되었다. 그 후 새로운 세대의 픽토리얼리즘 사진가들이 활발히 활동하기 시작했다. 이들에는 알렉세이 마주인, 세르게이 로보비코프(1870-1941), 피오트르 클레피코프, 바실리 울리틴(1888-1976), 니콜라이 안드레예프(1871-1919), 니콜라이 스비쉬초프-파올라, 레오니드 쇼킨(1896-1962), 알렉산더 그린베르크(1885-1979) 등이 포함되었다. 1894년, 모스크바에 러시아 사진 협회가 설립되었으나, 회원들 간의 의견 차이로 인해 두 번째 단체인 모스크바 예술 사진 협회가 설립되었다. 두 단체 모두 수년간 러시아에서 픽토리얼리즘을 촉진한 주요 단체였다.

Pictorialism spread to Russia first through European magazines and was championed by photography pioneers Evgeny Vishnyakov in Russia and Jan Bulhak from Poland. Soon after a new generation of pictorialists became active. These included Aleksei Mazuin, Sergei Lobovikov, Piotr Klepikov, Vassily Ulitin, Nikolay Andreyev, Nikolai Svishchov-Paola, Leonid Shokin, and Alexander Grinberg. In 1894 the Russian Photographic Society was established in Moscow, but differences of opinion among the members led to the establishment of a second organization, the Moscow Society of Art Photography. Both were the primary promoters of pictorialism in Russia for many years.

스페인

Spain

스페인에서 픽토리얼리즘 사진의 주요 중심지는 마드리드와 바르셀로나였다. 마드리드에서 이 운동을 이끈 사람은 안토니오 카노바스로, 그는 〈레알 소시에다드 포토그라피카 드 마드리드〉를 창립하고 잡지 《라 포토그라피아》를 편집했다. 카노바스는 자신이 스페인에 예술사진을 처음 소개했다고 주장했지만, 그의 경력 전반에 걸쳐 그는 초기 영국 픽토리얼리즘 사진가들, 특히 로빈슨과 같은 알레고리적 스타일에 뿌리를 두고 있었다. 그는 자신의 인화물에서 어떠한 표면 조작도 거부했으며, 그런 스타일은 “사진이 아니다. 사진일 수 없으며, 절대로 사진이 될 수 없다”고 말했다. 이 외에도 카를로스 이니고, 마누엘 레논, 호안 빌라토바(1878-1954), 그리고 콘데 데 라 벤토사라는 인물들이 스페인에서 영향을 미친 사진가들이다. 유럽의 다른 지역과 달리, 픽토리얼리즘은 1920년대와 1930년대 동안 스페인에서 여전히 인기를 끌었으며, 벤토사는 그 시기의 가장 다작한 픽토리얼리즘 사진가였다. 불행히도 이들 사진가들의 원본 인화물은 매우 적게 남아 있으며, 그들의 이미지 대부분은 현재 잡지 재현을 통해서만 알려져 있다.

The main centers of pictorial photography in Spain were Madrid and Barcelona. Leading the movement in Madrid was Antonio Cánovas, who founded the Real Sociedad Fotográfica de Madrid and edited the magazine La Fotografía . Cánovas claimed to be the first to introduce artistic photography to Spain, but throughout his career he remained rooted in the allegorical style of the early English pictorialists like Robinson. He refused to use any surface manipulation in his prints, saying that style “is not, cannot be and will never be photography.”. Other influential photographers in the country were Carlos Iñigo, Manual Renon, Joan Vilatobà and a person known only as the Conde de la Ventosa. Unlike the rest of Europe, pictorialism remained popular in Spain throughout the 1920s and 1930s, and Ventosa was the most prolific pictorialist of that period. Unfortunately very few original prints remain from any of these photographers; most of their images are now known only from magazine reproductions.

미국

United States

픽토리얼리즘의 정의와 방향을 설정하는 데 있어 중요한 인물 중 하나는 미국의 알프레드 스티글리츠였다. 그는 아마추어로 시작했지만, 픽토리얼리즘의 홍보를 자신의 직업이자 집념으로 삼았다. 그의의 저술, 조직 활동, 그리고 픽토리얼리즘 사진가들을 발전시키고 홍보하려는 개인적인 노력 덕분에, 스티글리츠는 픽토리얼리즘의 시작부터 끝까지 지배적인 인물로 자리 잡았다. 독일 사진가들의 발자취를 따라, 스티글리츠는 1892년 뉴욕에서 〈포토-시세션〉이라는 단체를 설립했다. 스티글리츠는 이 단체의 회원들을 직접 선발했으며, 단체의 활동 방향과 시기를 철저히 통제했다. 그는 거트루드 케시비어, 에바 왓슨 슈체, 앨빈 랭던 코번, 에드워드 스타이켄, 조지프 케일리 등 자신의 비전에 부합하는 사진가들을 선택해, 사진을 예술로 인정받으려는 운동에 엄청난 개인적, 집단적 영향을 미친 친구들의 모임을 만들었다. 스티글리츠는 또한 그가 편집한 두 개의 출판물, 《카메라 노트》와 《카메라 워크》, 그리고 뉴욕에서 운영한 갤러리를 통해 지속적으로 픽토리얼리즘을 홍보했다. 이 갤러리인 〈더 리틀 갤러리스 오브 더 포토-시세션〉은 오랜 기간 동안 픽토리얼리즘 사진가들의 작품만을 전시했다.

One of the key figures in establishing both the definition and direction of pictorialism was American Alfred Stieglitz, who began as an amateur but quickly made the promotion of pictorialism his profession and obsession. Through his writings, his organizing and his personal efforts to advance and promote pictorial photographers, Stieglitz was a dominant figure in pictorialism from its beginnings to its end. Following in the footsteps of German photographers, in 1892 Stieglitz established a group he called the Photo-Secession in New York. Stieglitz hand-picked the members of the group, and he tightly controlled what it did and when it did it. By selecting photographers whose vision was aligned with his, including Gertrude Käsebier, Eva Watson-Schütze, Alvin Langdon Coburn, Edward Steichen, and Joseph Keiley, Stieglitz built a circle of friends who had enormous individual and collective influence over the movement to have photography accepted as art. Stieglitz also continually promoted pictorialism through two publications he edited, Camera Notes and Camera Work and by establishing and running a gallery in New York that for many years exhibited only pictorial photographers (the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession).

초기에 많은 활동이 스티글리츠를 중심으로 이루어졌지만, 미국에서 픽토리얼리즘은 뉴욕에 국한되지 않았다. 보스턴에서는 F. 홀랜드 데이가 당시 가장 다작하며 주목받는 픽토리얼리즘 사진가 중 한 사람이었다. 오하이오에서 뛰어난 픽토리얼리즘 사진을 제작한 클라렌스 H. 화이트는 이후 새로운 세대의 사진가들을 가르쳤다. 서부 해안에서는 〈캘리포니아 카메라 클럽〉과 〈남부 캘리포니아 카메라 클럽〉이 두드러졌으며, 여기에는 앤 브리그만(1869-1950), 아르놀트 겐테(1869-1942), 아델라이드 한스콤 리슨(1875-1931), 에밀리 피치포드(1878-1956), 윌리엄 에드워드 다손빌(1879-1957)과 같은 주요 픽토리얼리즘 사진가들이 포함되었다. 이후 시애틀에서는 일본계 미국인 픽토리얼리스트들, 예를 들어 코이케 쿄(1878-1947), 쿠니시게 “프랭크” 아사키치(1878-1960), 마츠시타 이와오(1892-1979)가 중심이 되어 〈시애틀 카메라 클럽〉을 설립했다. 이후 엘라 E. 맥브라이드(1862-1965)와 스나미 소이치(Soichi Sunami)와 같은 저명한 회원들이 합류했다.

While much initially centered on Stieglitz, pictorialism in the U.S. was not limited to New York. In Boston F. Holland Day was one of the most prolific and noted pictorialists of his time. Clarence H. White, who produced extraordinary pictorial photographs while in Ohio, went on to teach a whole new generation of photographers. On the West Coast the California Camera Club and Southern California Camera Club included prominent pictorialists Annie Brigman, Arnold Genthe, Adelaide Hanscom Leeson, Emily Pitchford and William Edward Dassonville. Later on, the Seattle Camera Club was started by a group of Japanese-American pictorialists, including Dr. Kyo Koike, Frank Asakichi Kunishige and Iwao Matsushita (prominent members later included Ella E. McBride and Soichi Sunami).

기법

Techniques

픽토리얼리즘 사진가들은 일반적인 유리판이나 필름 네거티브에서 작업을 시작했다. 일부는 장면의 초점을 조정하거나 특별한 렌즈를 사용해 부드러운 이미지를 만들었지만, 대부분의 경우 최종 사진의 외관은 인화 과정에서 결정되었다. 픽토리얼리스트들은 다양한 종이와 화학적 공정을 사용하여 특정 효과를 내고, 일부는 브러시, 잉크 또는 안료를 사용해 인화물의 톤과 표면을 조작하기도 했다. 다음은 가장 일반적으로 사용된 회화주의 공정들의 목록이다. 자세한 내용은 크로포드의 저서 그리고 다움, 리브몽, 프로저의 저서에서 확인할 수 있다. 별도 언급이 없는 한, 아래 설명은 이 두 권의 책에서 요약한 것이다.

Pictorial photographers began by taking an ordinary glass-plate or film negative. Some adjusted the focus of the scene or used a special lens to produce a softer image, but for the most part the printing process controlled the final appearance of the photograph. Pictorialists used a variety of papers and chemical processes to produce particular effects, and some then manipulated the tones and surface of prints with brushes, ink or pigments. The following is a list of the most commonly used pictorial processes. Readers can find more details in books by Crawford and in Daum, Ribemont, and Prodger. Unless otherwise noted, the descriptions below are summarized from these two books.

- 브로모일 프로세스: 이 프로세스는 오일 프린트 프로세스의 변형으로, 프린트를 확대할 수 있게 한다. 이 과정에서 일반적인 실버 젤라틴 프린트를 제작한 후, 이 프린트를 중크롬산칼륨 용액으로 표백한다. 이는 프린트 표면을 경화시키고 잉크가 표면에 부착되도록 한다. 브로모일 프린트의 밝은 영역과 어두운 영역 모두를 조작할 수 있어 오일 프린트보다 더 넓은 톤 범위를 제공한다.

- 카본 프린트: 이 프린트는 중크롬산칼륨, 카본 블랙 또는 다른 색소와 젤라틴을 티슈 페이퍼에 코팅하여 제작되는 매우 섬세한 프린트다. 카본 프린트는 놀라운 디테일을 제공하며, 모든 사진 프린트 중에서도 가장 영구적인 것 중 하나로 꼽힌다. 처리 전후의 용지 안정성으로 인해, 카본 프린팅 티슈는 상업적으로 가장 먼저 제작된 사진 제품 중 하나였다.

- 시아노타입(청사진): 초기 사진 기법 중 하나인 시아노타입은 픽토리얼리스트들이 깊은 파란색 톤을 실험하면서 잠시 부활의 시기를 겪었다. 이 색상은 빛에 반응하는 철염으로 종이를 코팅하여 만들어졌다.

- 검 프린트: 픽토리얼리스트들이 특히 선호했던 기법 중 하나로, 종이에 아라비아 고무, 중크롬산칼륨, 그리고 하나 이상의 예술용 색소를 혼합하여 발라 제작되었다. 이 감광성 용액은 빛이 닿는 부분에서 서서히 경화되며, 이러한 영역은 몇 시간 동안 유연한 상태를 유지한다. 사진가는 용액의 혼합 비율을 조정하거나 노출 시간을 짧게 또는 길게 설정하며, 노출 후 색소가 발린 영역을 브러싱하거나 문질러 제어할 수 있었다.

- 오일 프린트 프로세스: 아라비아 고무와 젤라틴 용액으로 코팅된 종이에 기름기 있는 잉크를 적용하여 제작된다. 네거티브를 통해 노출되면 빛이 닿은 부분의 고무-젤라틴이 경화되고, 노출되지 않은 부분은 부드러운 상태로 남는다. 이후 브러시로 예술용 잉크를 발라주면 잉크는 경화된 부분에만 부착된다. 이 과정을 통해 사진가는 검 프린트의 밝은 영역을 조작할 수 있으며, 어두운 영역은 안정적으로 유지된다. 오일 프린트는 네거티브와 직접 접촉해야 하므로 확대할 수 없다.

- 플래티넘 프린트: 플래티넘 프린트는 두 단계의 과정을 필요로 한다. 먼저, 종이를 철염으로 감광 처리한 후 네거티브와 접촉시켜 희미한 이미지가 형성될 때까지 노출한다. 그런 다음, 화학적 현상 과정을 통해 철염이 플래티넘으로 대체된다. 이를 통해 매우 넓은 톤 범위를 가지며 각각이 강렬하게 표현된 이미지를 생성한다.

- Bromoil process: This is a variant on the oil print process that allows a print to be enlarged. In this process a regular silver gelatin print is made, then bleached in a solution of potassium bichromate. This hardens the surface of the print and allows ink to stick to it. Both the lighter and darker areas of a bromoil print may be manipulated, providing a broader tonal range than an oil print.

- Carbon print: This is an extremely delicate print made by coating tissue paper with potassium bichromate, carbon black or another pigment and gelatin. Carbon prints can provide extraordinary detail and are among the most permanent of all photographic prints. Due to the stability of the paper both before and after processing, carbon printing tissue was one of the earliest commercially made photographic products.

- Cyanotype: One of the earliest photographic processes, cyanotypes experienced a brief renewal when pictorialists experimented with their deep blue color tones. The color came from coating paper with light-sensitive iron salts.

- Gum bichromate: One of the pictorialists’ favorites, these prints were made by applying gum arabic, potassium bichromate and one or more artist’s colored pigments to paper. This sensitized solution slowly hardens where light strikes it, and these areas remain pliable for several hours. The photographer had a great deal of control by varying the mixture of the solution, allowing a shorter or longer exposure and by brushing or rubbing the pigmented areas after exposure.

- Oil print process: Made by applying greasy inks to paper coated with a solution of gum bichromate and gelatin. When exposed through a negative, the gum-gelatin hardens where light strikes it while unexposed areas remain soft. Artist’s inks are then applied by brush, and the inks adhere only to the hardened areas. Through this process a photographer can manipulate the lighter areas of a gum print while the darker areas remain stable. An oil print cannot be enlarged since it has to be in direct contact with the negative.

- Platinum print: Platinum prints require a two-steps process. First, paper is sensitized with iron salts and exposed in contact with a negative until a faint image is formed. Then the paper is chemically developed in a process that replaces the iron salts with platinum. This produces an image with a very wide range of tones, each intensely realized.

픽토리얼리즘 사진가

Pictorial photographers

다음은 경력 동안 픽토리얼리즘에 참여한 저명한 사진가들의 두 목록이다. 첫 번째 목록은 경력의 전부 또는 거의 전부를 픽토리얼리즘에 전념한 사진가들(주로 1880년부터 1920년까지 활동한 이들)을 포함한다. 두 번째 목록은 경력 초기에 픽토리얼 스타일을 사용했지만, 순수 사진 또는 스트레이트 포토그래피로 더 잘 알려진 20세기 사진가들을 포함한다.

Following are two lists of prominent photographers who engaged in pictorialism during their careers. The first list includes photographers who were predominantly pictorialists for all or almost all of their careers (generally those active from 1880 to 1920). The second list includes 20th-century photographers who used a pictorial style early in the careers but who are more well known for pure or straight photography.

주로 픽토리얼리스트였던 사진가

Photographers who were predominantly pictorialists

- 웨인 알비, 1882–1937, 미국인

- 제임스 크레이그 아난, 1846–1946, 스코틀랜드인

- 자이다 벤-유수프, 1869–1933, 미국인

- 페르낭 비뇽, 1888–1969, 프랑스인

- 앨리스 보튼, 1866?–1943, 미국인

- 애니 브리그먼, 1869–1950, 미국인

- 앨리스 버, 1883-1968, 미국인

- 블라디미르 진드리치 부프카, 1887-1916, 체코인

- 얀 부학, 1876-1950, 폴란드인

- 해롤드 카즈노, 1878-1953, 호주인

- 로즈 클락, 1852-1942, 미국인

- 앨빈 랭던 코번, 1882-1966, 미국인

- F. 홀랜드 데이, 1864-1933, 미국인

- 조지 데이비슨, 1854-1930, 영국인

- 로버트 드마시, 1859-1936, 프랑스인

- 메리 데븐스, 1857-1920, 미국인

- 피에르 뒤브뢰유, 1872-1944, 프랑스인

- 루돌프 아이케마이어 주니어, 1862-1932, 미국인

- 피터 헨리 에머슨, 1856-1936, 영국인

- 프레드릭 H. 에반스, 1853-1943, 영국인

- 프랭크 유진, 1865-1936, 미국인

- 오가와 이신, 1860-1929, 일본인

- S. D. 주하르, 1901-1963, 영국인

- 거트루드 케시비어 1852-1934, 미국인

- 가지마 세이베이, 1866-1924, 일본인

- 조셉 킬리, 1869-1914, 미국

- 코이케 쿄, 1878-1947, 일본계 미국인

- 하인리히 쿤, 1866-1944, 오스트리아인

- 사라 래드, 1860-1927, 미국인

- 애들레이드 핸스콤 리슨, 1875-1931, 미국인

- 유진 르메르, 1874-1948, 벨기에인

- 귀스타브 마리시우, 1872-1929, 벨기에인

- 아돌프 드 메이어, 1868-1949, 프랑스인

- 레오나르 미손, 1870-1943, 벨기에인

- 윌리엄 모텐슨, 1897-1965, 미국인

- 오가와 가즈마사, 1860-1929, 일본인

- 콩스탕 퓌요, 1857-1933, 프랑스인

- 제인 리스, 1868?-1961, 미국인

- 귀도 레이, 1861-1935, 이탈리아인

- 헨리 피치 로빈슨, 1830-1901, 영국인

- 사라 쇼트 시어스, 1858-1935, 미국인

- 조지 실리, 1880-1955, 미국인

- 클라라 시프렐, 1885-1975, 미국/캐나다인

- 칼 스트러스, 1886-1981, 미국인

- 미롱 셰를링, 1880-1951, 러시아인

- 프랭크 서트클리프, 1853-1941, 영국인

- 존 윌리엄 튀크로스,1871-1936, 호주인

- 엘리자베스 플린트 웨이드, 1849-1915, 미국인

- 아그네스 바르부르크, 1872-1953, 영국인

- 에바 왓슨-슈체, 1867-1935, 미국인

- 한스 바첵, 1843-1903, 오스트리아인

- 클라렌스 H. 화이트, 1871-1925, 미국인

- 마이라 앨버트 위긴스, 1869-1956, 미국인

- Wayne Albee, 1882–1937, American

- James Craig Annan, 1846–1946, Scottish

- Zaida Ben-Yusuf, 1869–1933, American

- Fernand Bignon [fr], 1888–1969, French

- Alice Boughton, 1866?–1943, American

- Annie Brigman, 1869–1950, American

- Alice Burr, 1883–1968, American

- Vladimír Jindřich Bufka, 1887–1916, Czech

- Jan Bułhak, 1876–1950, Polish

- Harold Cazneaux, 1878–1953, Australian

- Rose Clark, 1852–1942, American

- Alvin Langdon Coburn, 1882–1966, American/English

- F. Holland Day, 1864–1933, American

- George Davison, 1854–1930, English

- Robert Demachy, 1859–1936, French

- Mary Devens, 1857–1920, American

- Pierre Dubreuil, 1872–1944, French

- Rudolf Eickemeyer Jr., 1862–1932, American

- Peter Henry Emerson, 1856–1936, English

- Frederick H. Evans, 1853–1943, English

- Frank Eugene, 1865–1936, American

- Ogawa Isshin, 1860–1929, Japanese

- S. D. Jouhar, 1901–1963, British

- Gertrude Käsebier 1852–1934, American

- Kajima Seibei, 1866–1924, Japanese

- Joseph Keiley, 1869–1914

- Kyo Koike, 1878–1947, Japanese-American

- Heinrich Kühn, 1866–1944, Austrian

- Sarah Ladd, 1860–1927, American

- Adelaide Hanscom Leeson, 1875–1931, American

- Eugene Lemaire, 1874–1948, Belgian

- Gustave Marissiaux [fr], 1872–1929, Belgian

- Adoph de Meyer, 1868–1949, French/German

- Léonard Misonne, 1870–1943, Belgian

- William Mortensen, 1897–1965, American

- Ogawa Kazumasa, 1860–1929, Japanese

- Constant Puyo, 1857–1933, French

- Jane Reece, 1868?–1961, American

- Guido Rey [fr; it], 1861–1935, Italian

- Henry Peach Robinson, 1830–1901, English

- Sarah Choate Sears, 1858–1935, American

- George Seeley, 1880–1955, American

- Clara Sipprell, 1885–1975, American/Canadian

- Karl Struss, 1886–1981, American

- Miron A. Sherling, 1880–1951, Russian

- Frank Sutcliffe, 1853–1941, English

- John William Twycross,1871–1936, Australian

- Elizabeth Flint Wade, 1849–1915, American

- Agnes Warburg, 1872–1953, English

- Eva Watson-Schütze, 1867–1935, American

- Hans Watzek [de], 1843–1903, Austrian

- Clarence H. White, 1871–1925, American

- Myra Albert Wiggins, 1869–1956, American

픽토리얼리스트로 시작한 20세기 사진가

20th-century photographers who began as pictorialists

- 앤설 애덤스, 1902–1984, 미국인

- 세실 보스톡, 1884–1939, 호주인

- 올리브 코튼, 1911–2003, 호주인

- 이모겐 커닝햄, 1883–1976, 미국인

- 로라 길핀, 1891–1979, 미국인

- 마그리트 매더, 1886‒1952, 미국인

- 카를 마리아 우도 레메스, 1954–2014, 독일

- 스테파니 슈나이더, 1968–, 독일계 미국인

- 에드워드 스타이켄, 1879–1973, 미국인

- 알프레드 스티글리츠, 1864–1946, 미국인

- 스나미 소이치, 1885–1971, 일본계 미국인

- 에드워드 웨스턴, 1886–1958, 미국인

- Ansel Adams, 1902–1984, American

- Cecil Bostock, 1884–1939 Australian

- Olive Cotton, 1911–2003, Australian

- Imogen Cunningham, 1883–1976, American

- Laura Gilpin, 1891–1979, American

- Margrethe Mather, 1886‒1952, American

- Karl Maria Udo Remmes, 1954–2014, German

- Stefanie Schneider, born 1968, German American

- Edward Steichen, 1879–1973, American

- Alfred Stieglitz, 1864–1946, American

- Soichi Sunami, 1885–1971, Japanese-American

- Edward Weston, 1886–1958, American

- 출처 : 「Pictorialism」, Wikipedia(en), 2024.12.30.